Don't worry about LLMs

This is a near-transcript of the talk I gave at PyCon Italia 2024 in May in Florence.

Introduction

Buongiorno PyconIt, grazie per avermi invitata a parlare! Avrei voluta fare tutto il discorso in italiano, ma lo sto ancora imparando.

Per adesso posso parlare soltanto di gelato o colori. Perché non so ancora dire, “don’t worry about LLMs”, il resto sarà in inglese.

I’m Vicki and I work as a machine learning engineer at Mozilla.ai, building a platform to enable developers to evaluate and select between different LLMs. Before working on LLMs, I’ve built large-scale ML systems in security, social recommenders, and tv content recommendations

After working with LLMs for the past year, what I’ve found is that the new engineering systems we’re building around these LLMs are a lot like the old ones. Once we cut away the hype, what we’re usually left with are plain engineering and machine learning problems.

But how do we as practitioners cut away the hype? Since we are in Firenze, I want to tell a story I recently heard while talking to other tech folks that took place here that might help us to navigate this. Around town, there is a company called Medici Corp.

They are a very large organization, spread out into lots of different industries in banking, pharma, fine arts, and philanthropy. They were very successful, but recently, their CEO was worried about being left behind in AI.

And she wanted to see if there was some way they could incorporate a chatbot or similar into their offerings.

The CEO created a small R&D task force of developers and machine learning engineers and tasked them with investigating what it would take to add AI to their product over the course of a sprint.

Now, the developers, machine learning engineers, and PMs, were all very experienced in industry, but new to LLMs, and when they started looking at all the different model choices, platforms, and the buzz around LLMs, they became very distraught.

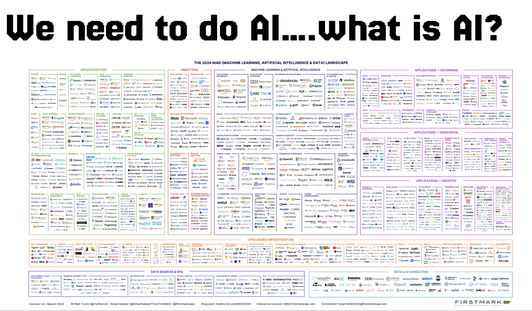

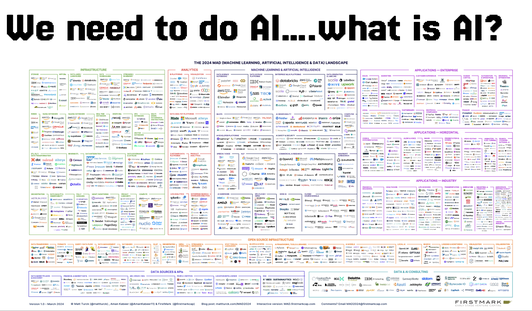

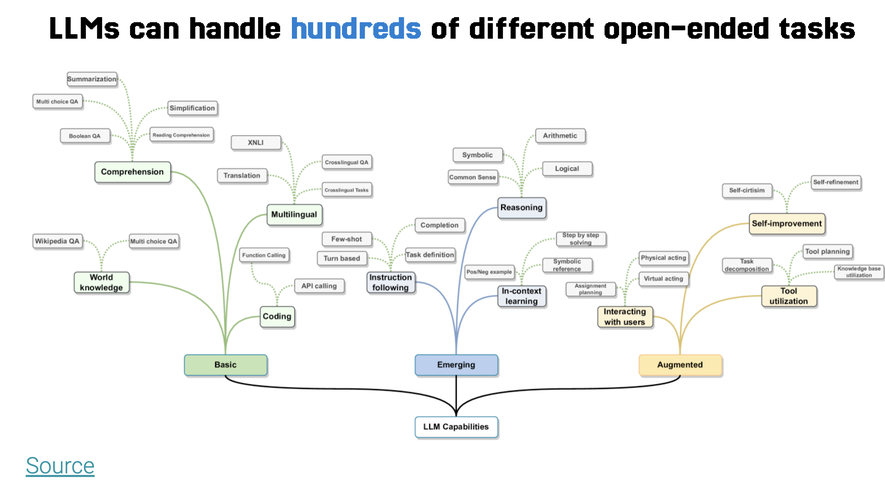

There were too many open-ended options , a lot of people who were loud online. So, the developers decided to rent an Airbnb outside the city for a week so they could really focus, isolate, and ship some code. When they got together around a whiteboard, they frantically started researching what tools to build an LLM with, and what they saw was this chart.

“What do we do,” they asked. How were they going to compete in this insanely crowded market? More importantly, how could they as engineers even understand this landscape?

As they worried their team lead stepped forward and said, “In times like these, I turn to the wisdom of the foundational thinkers. There is one who said,

The developers turned to the team lead and said, “This man says the truth, but how can we possibly turn this into actionable advice that we can write features for with feature flags and unit tests in a two-week sprint? And deliver a product that has a magic emoji on it?” In other words, “How do we deliver AI?”

The team lead said, “Here’s what we’re going to do. We’re going to get in small groups and research what other people have done in the situation, and then we’re going to present what other people did.”

The engineers groaned, because group work is the worst. But the team lead said, “Reading about what people in the past have done is the only way to build and keep our context window, which is our knowledge base of classical architecture patterns and historical engineering context that allows us to make good, grounded engineering decisions.”

The Singular Machine Learning Task

So the engineers agreed and went off to do research. All day the engineers researched and read, and the next day, they all gathered in a group. One stepped forward, and began to tell her story.

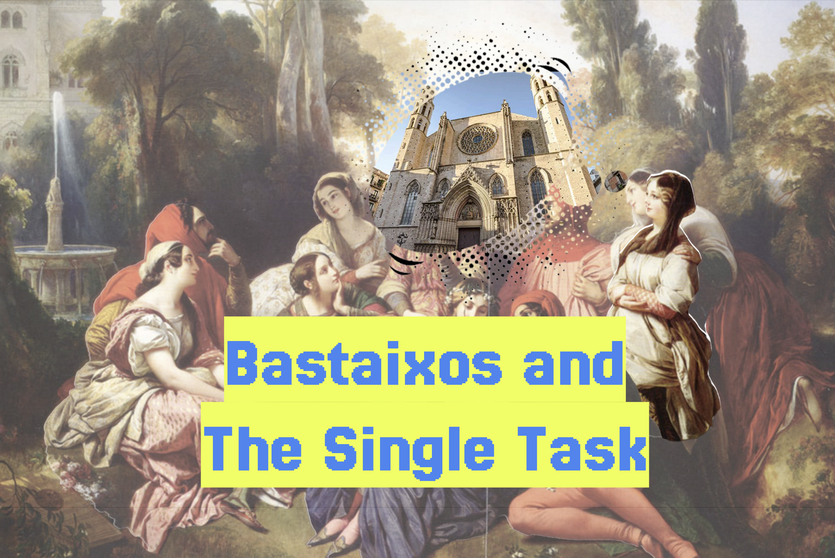

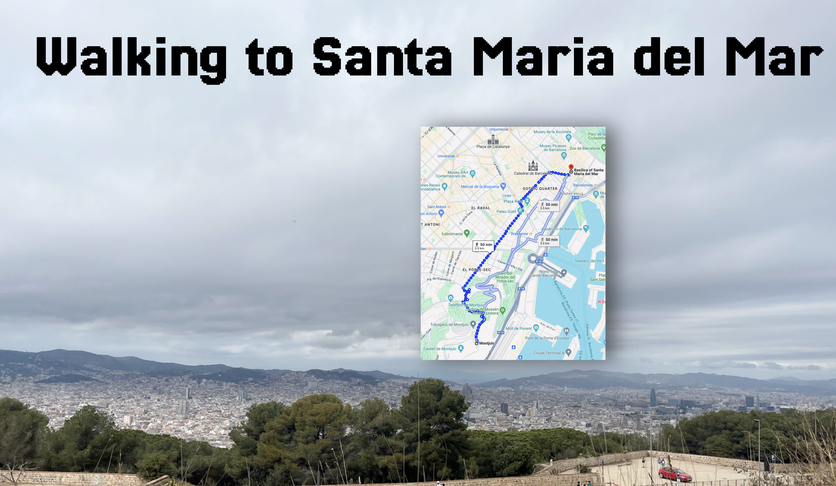

She said, once upon a time in Barcelona, they were building a grand cathedral, called Santa Maria Del Mar. At that time, many Gothic cathedrals were built in periods that took a long amount of time, usually fifty to one hundred years. Santa Maria del Mar was finished in only fifty five, even notwithstanding a fire and the plague that started the neighborhood where it was being built, and is the only church surviving in the Catalan Gothic style.

It’s unique because it was one of the only churches built with backing from commoners as opposed to the nobility of the city of Barcelona. The rich would pay with their money, and the poor would pay with their labor, for the neighborhood to build the cathedral together.

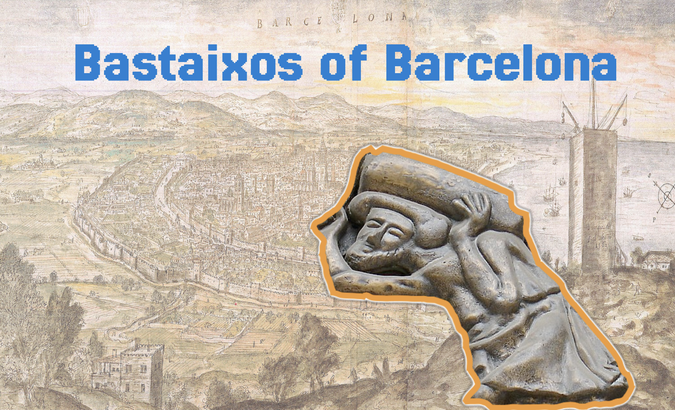

A key force on the project were the bastaixos, or porters. They had an organized guild, and these men were traditionally in charge of loading and unloading ships. They were already extremely good at one thing: carrying heavy things. When they heard about the cathedral, the guild volunteered to take the stones from the royal quarry at Montjuïc, at a high elevation above the city, to the cathedral.

Right now, to get from here to the Cathedral, it takes about 50 minutes to walk, downward. In those days, the bastaixos would have walked past the Port of Barcelona to get there, taking longer, over an hour, carrying a stone that weighs over 40kg on his back alone.

So a bastaix would first put the stone on his back, and then move it all the way to the cathedral. Then, he would go back and move another stone. They did this all day, day-in and day out. The stones weighed 40 kg and the only protection they had was the turban on their head, called a capcana that rolled up above the neck.

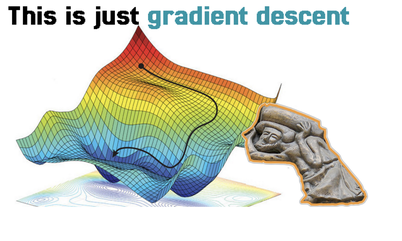

The machine learning engineer paused and said, you know, now that I’m telling this story, it reminds me of something, and that something is gradient descent.

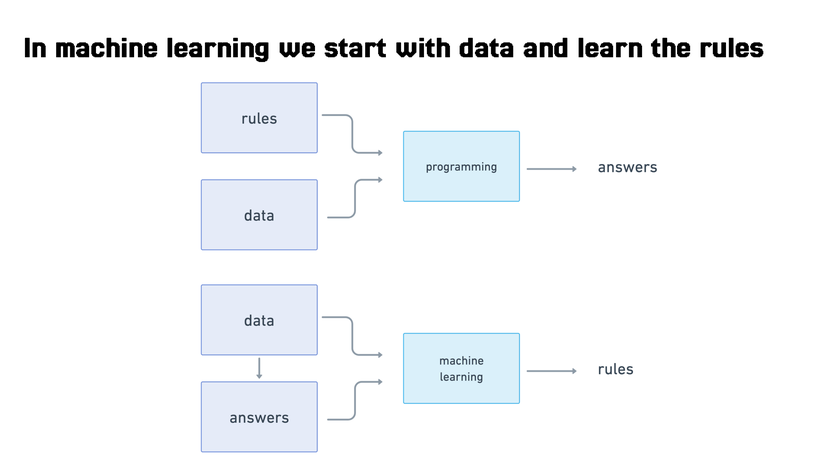

Gradient descent is a key algorithm that many machine learning models, including neural networks in the transformer family that powers GPT-style models, use for training the model.

Gradient descent minimizes the loss function by iteratively adjusting the model’s parameters (weights and biases). The process involves calculating the gradient of the loss function with respect to the model parameters and then updating these parameters in the direction that reduces the loss.

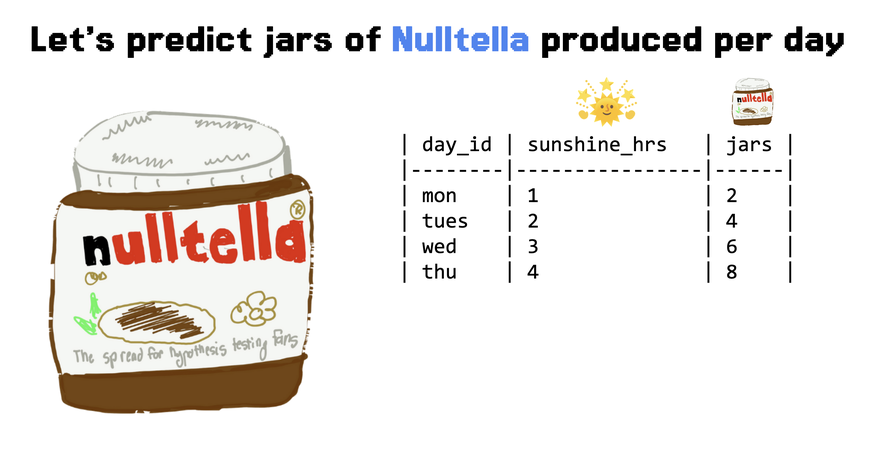

For example, let’s say that we produce artisanal hazelnut spread for statisticians, Nulltella. We want to predict how many jars of Nulltella we’ll produce on any given day. Let’s say we have some data available to us, and that is, how many hours of sunshine we have per day, and how many jars of Nulltella we’ve been able to produce every day.

It turns out that we feel more inspired to produce hazelnut spread when it’s sunny out. We can clearly see this relationship between input and output in our data (we do not produce Nulltella Friday-Sunday because we prefer to spend those days talking about Python.)

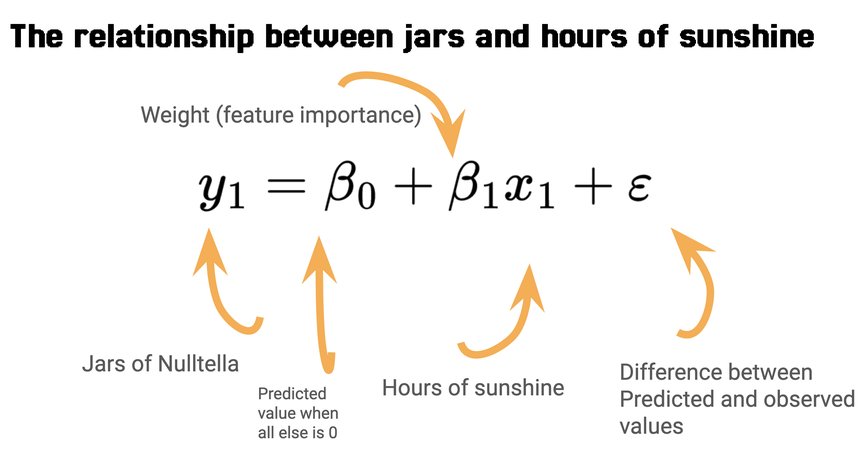

Now that we have our data, we need to write our prediction algorithm, where we know, based on our current values, what future values could potentially be. The equation to predict output Y from inputs X for linear regression is outlined here.

Our task is to continuously adjust our weights and biases for all of our features to optimally solve this equation for the difference between our actual as presented by our data and a prediction based on the algorithm to find the smallest sum of squared differences, between each point and the line.

In other words, we’d like to minimize epsilon, because it will mean that, at each point, our predicted Y is as close to our actual Y as we can get, given the other points.

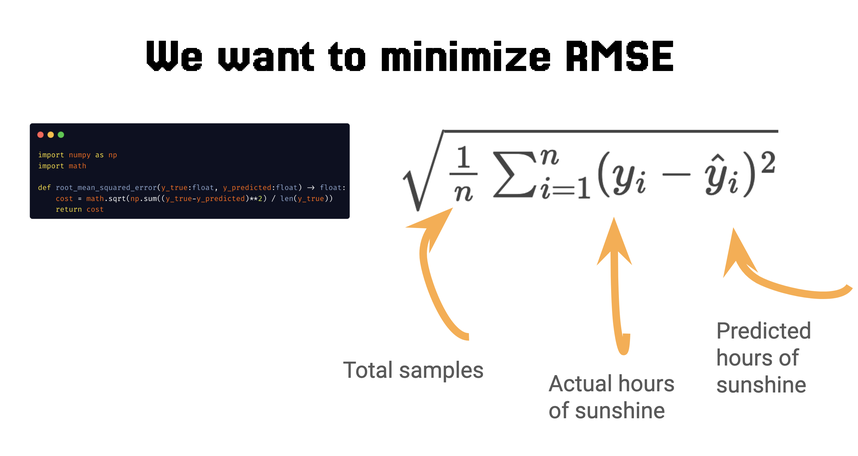

The equation we use for this is RMSE (Root mean squared error).

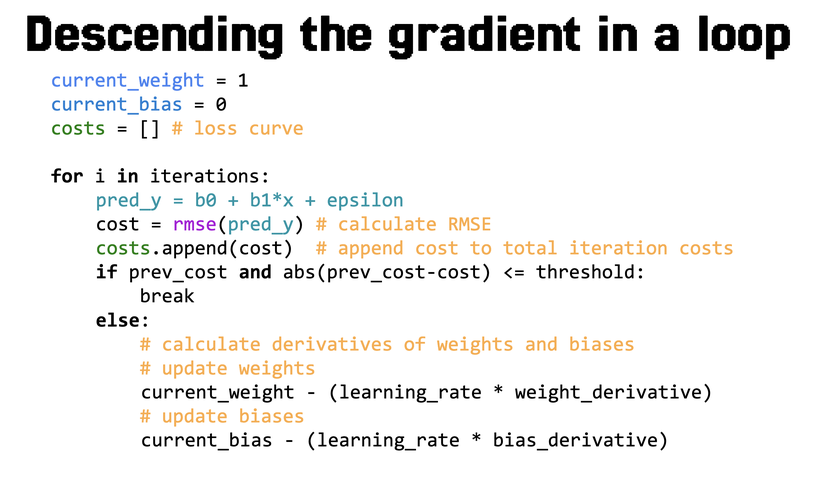

Let’s say we initialize the function with some x values and weights. How do we optimize it? Using gradient descent. We start with either zeros or randomly-initialized values for the weights and continue recalculating both the weights and error term until we come to an optimal stopping point. We’ll know we’re succeeding because our loss, as calculated by RMSE should incrementally decrease in every training iteration.

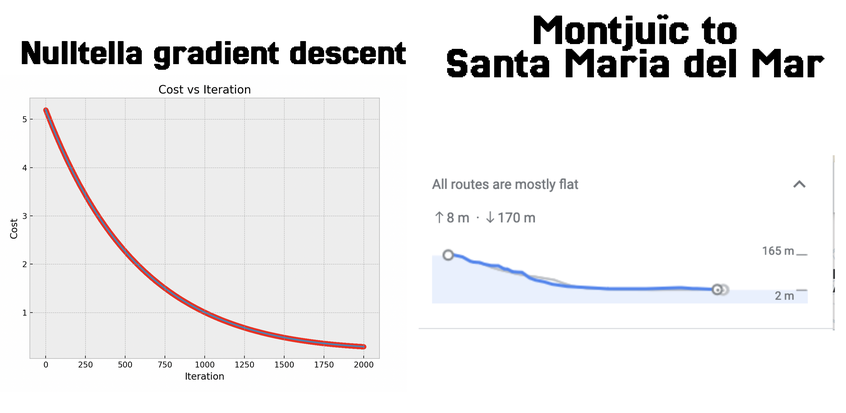

For our particular model, we can see that the loss curve reaches a local minimum after ten iterations. If you look at the curve for the elevation the bastaixos walked from Montjuic to Santa Maria del Mar, you’ll see that it follows the same pattern.

That’s because these two things lay out a fundamental pattern: working on optimizing one thing at a time.

The bastaixos had a single goal: the completion of the cathedral, and the single functionality of carrying stones to that goal. They didn’t work on carving the stone, nor on the stained glass, nor on architecture. They just moved rocks. Everything else was peripheral, and the focus allowed them to get just one great thing done. The engineers realized that they also needed to learn to be bastaixos and focus on a single machine learning task.

But what they realized was that LLMs in and of themselves, while also operating on the principle of gradient descent, are set up to solve an unbounded number of open-ended tasks: they can write poems, complete recipes, classify text, summarize text, evaluate other models, act as chatbots, and much, much more.

When the engineers went back to the drawing board, it was clear what they needed: the focus on a single use-case for their customers. What’s the best way to figure out what you need LLMs for? List all the problems your business is facing and see if machine learning will be the right way to address them.

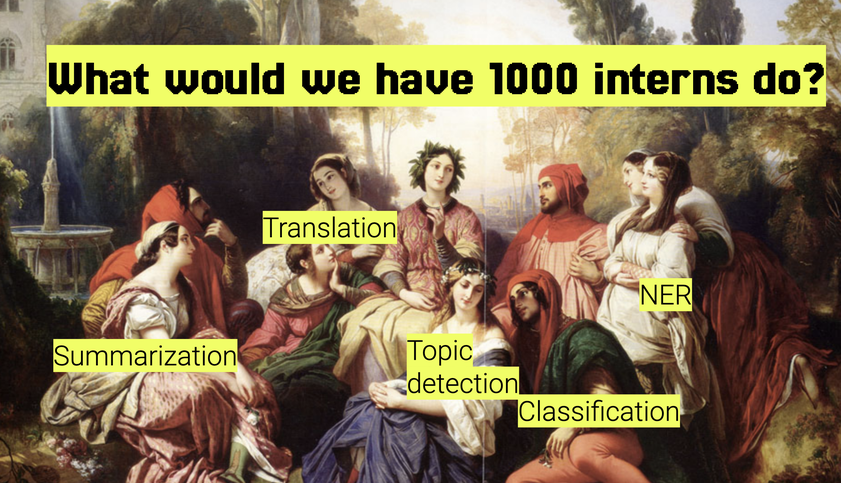

Machine learning generally, and LLMs more specifically, are good for where the number of heuristics you develop starts to outweigh their maintenance cost. I’ve heard this also called the 1000-intern heuristic: if it’s a task that can be simplified by a thousand people entirely new to the task doing it, then do that.

The simplest tasks for large language models to do are summarization, classification, translation, named entity recognition, and similar. If your problems fall in that space, you’ll have an easier time than with open-ended tasks like reasoning. This is also the reason why, often, simpler models perform better for specific tasks than general LLMs that are meant to generalize to out-of-distribution tasks.

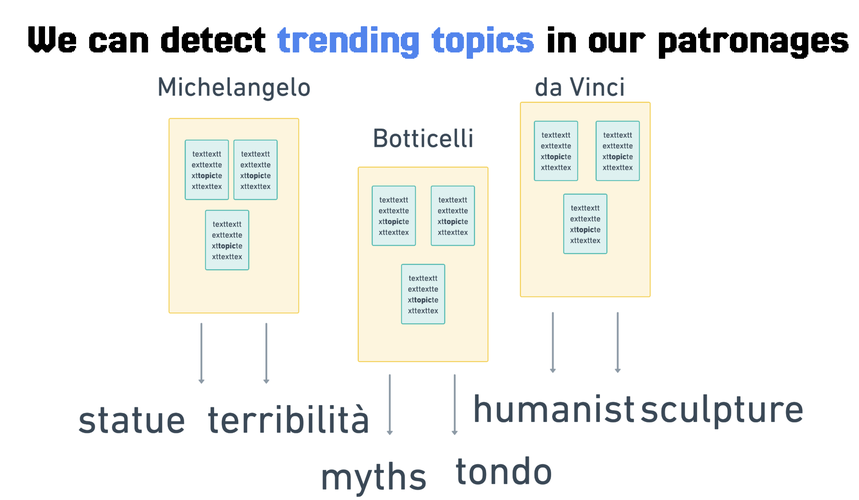

When the team thought about all the numerous things their company did, what they realized is that one of their biggest problems was trending topic detection: they have a lot of documents constantly floating around, particularly around the patronages they’re performing, and they perform a lot of art patronage.

They wanted to be able to get a sense of the types of art and types of artists in the hands of the corporation at any given time so they could further explore those trends and make sure their art funding was even.

Armed with this information, The Medici team decided that they wanted to use it internally to look at all the documents they had related to the large trove of artwork they had acquired. It would be easier to do internal topic detection than other outward-facing use-cases because they had subject-matter experts, and the categories of art were fairly established since they had in-house art experts. They presented this plan to the CEO, who was pleased. Now, they were at their next task, but they were still overwhelmed.

The Measurable Goal

On the second day, another developer had a story. She said, I’ve been reading about medieval monks.

Jamie Keiner, at the Department of Classics in the University of Georgia, wrote a book called “The Wandering Mind”, about how medieval monks used to harness attention to make their prayers more effective. Every day, their goal was to get higher on the spiritual plane away from earthly matters. But they kept getting distracted by the daily minutiae of life - legal disputes, farming and livestock, gossip, banality of everyday life that overloads your attention.

From the writings of one monk, John Cassian, a Christian monk in the Roman empire, for example, who traveled to Egypt, it turns out that distractions are not new: In the 420s, he wrote that “the mind gets pushed around by random distractions.” Like him, many monks and nuns saw distraction as a “primordial struggle”, and something they felt obligated to continually fight

What monks and nuns recognized is that, if they wanted to get closer to true understanding, they would have to separate from distractions that bound them to society, because it was impossible to focus on one thing at a time, and they only wanted to focus on prayer. As a monk called Hildemar of Civate put, “it is impossible to focus on two things at once - “in uno homine duas intentiones esse non posse.”

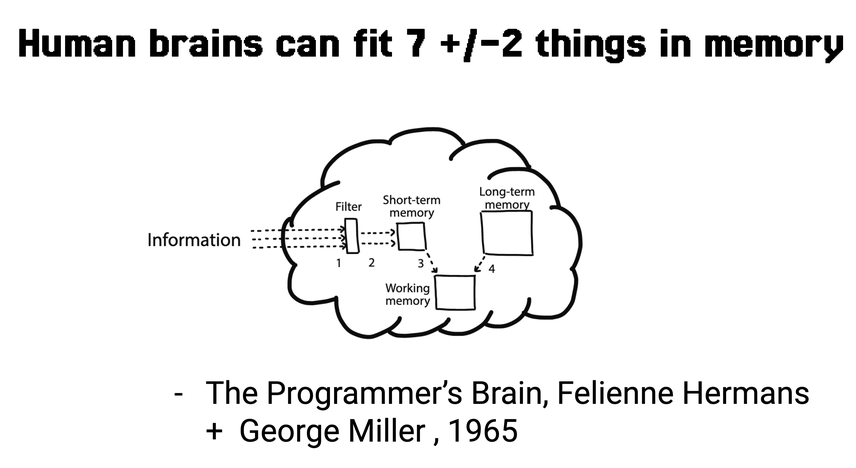

Much later, scientists confirmed that human brains have very poor capabilities for multitasking, as well. The most items a human can hold in memory is about 7, plus or minus two, and we definitely cannot do two things simultaneously. After 7 items our cache is cleared and we start getting confused and lost.

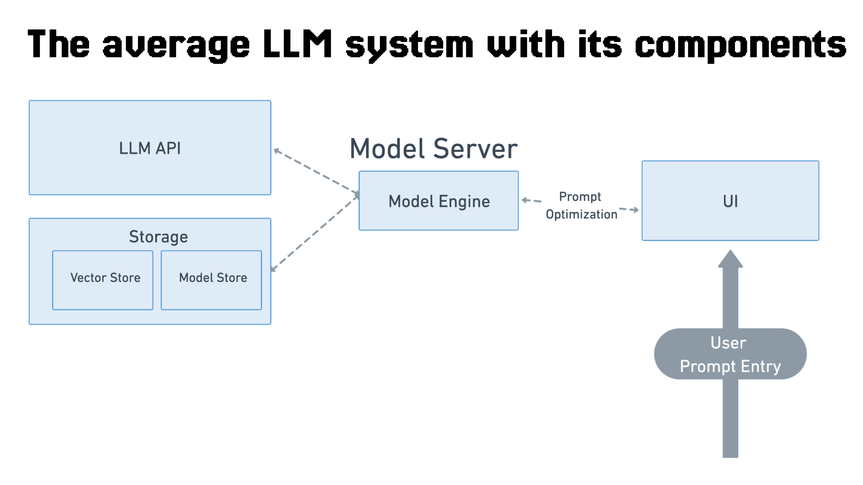

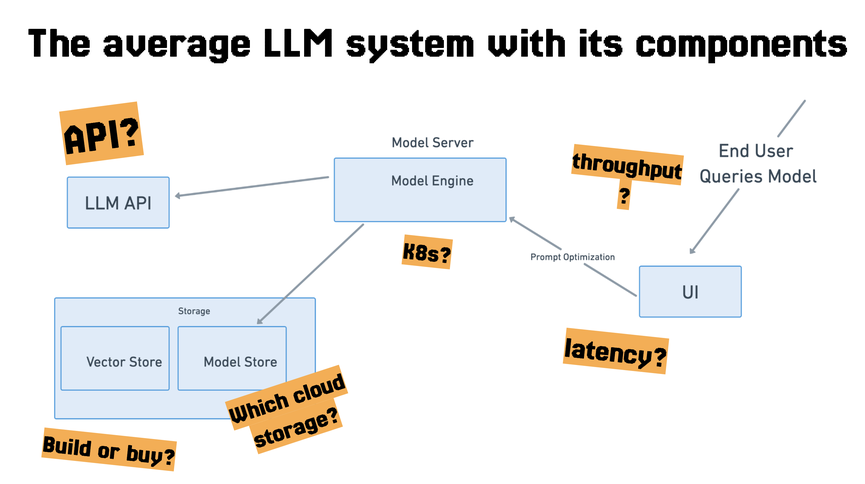

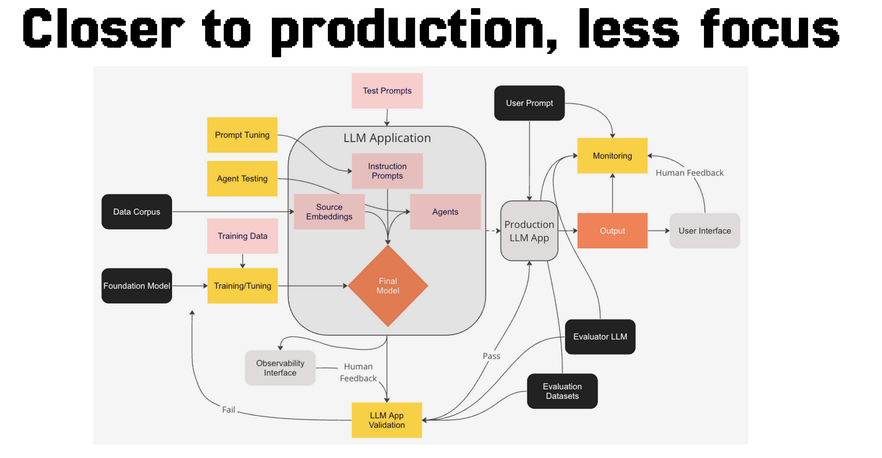

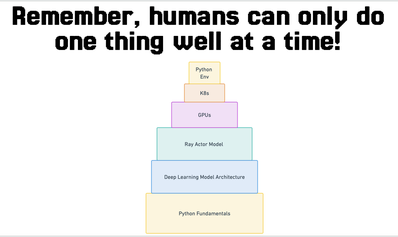

That means when we as engineers try to build large systems with multiple components, with large amounts of decisions to be made, the brain will shut down. This is the case in the LLM land today. The average LLM system might look something like this.

Each of these components is a million decisions to be made. Here is a list I can tick off just by looking at this diagram.

- Should we use our own model or an open-source base-model or an API vendor? Which API vendor?

- How should we go about testing our prompts? How should we constrain the outputs of the model? + Do we want to generate plain text, or JSON, or binary responses?

- What kind of UI do we need? Is text-based chat enough?

- Where do we store the model artifact - do we store it locally

- Are we using cloud vendors, are we using their implementations of cloud artifacts?

- Are we doing model fine-tuning, do we need separate data-collection mechanisms?

- How do we evaluate this model?

The monks told us that, even though we will have a lot of distractions and environmental variables, we need to focus on developing one good piece of software at a time as we build.

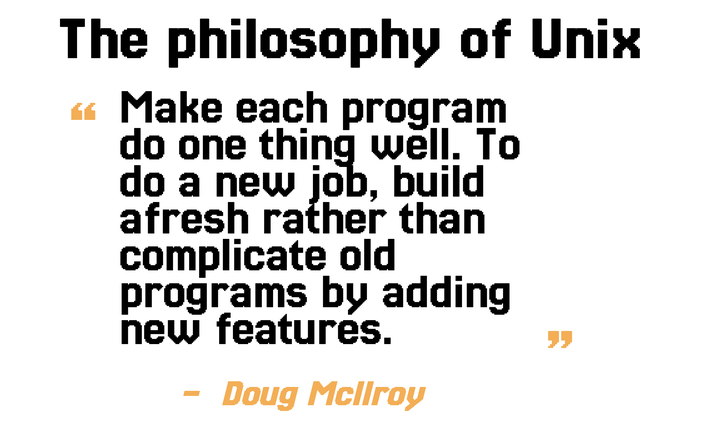

The developer telling the story said this reminds me of another established traditional development pattern: the philosophy of Unix, which says, tools that we build should be minimal and modular and do one thing at a time so we can combine them together later.

It’s true that when we build machine learning systems, we have no choice: we need vector databases, and APIs, and data stores, and, most importantly, models. But, when we build an entire machine learning system at once, for example, connecting five different APIs rather than one, or trying five models rather than one, five use-cases, we see a deterioration at each stage of the process rather than focusing on streamlining a single use-case and task end-to-end.

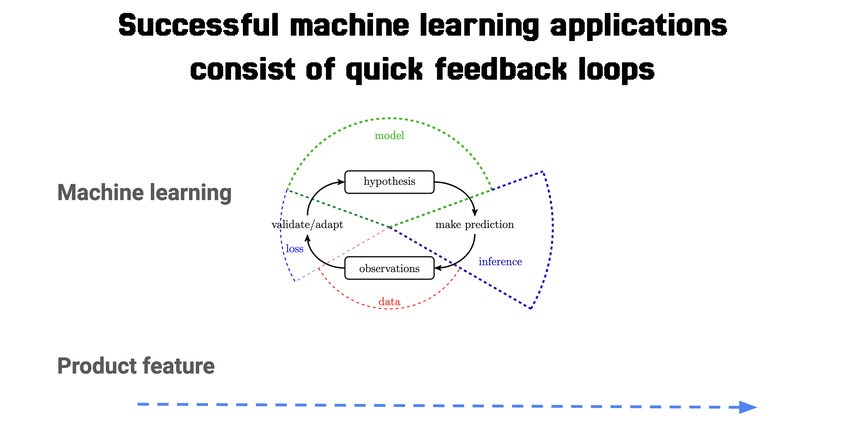

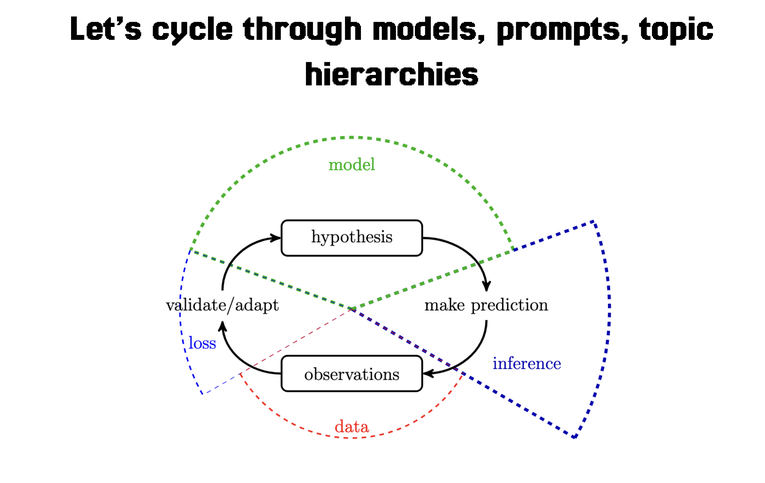

How do we get to programs that do one thing well in machine learning, i.e. perform our task of topic detection? The best way is to understand first that machine learning, unlike developing product features like “the ability to click a button” or “sending data to the database”, is a cyclical process that involves a lot of iteration before we get something working we’re happy with, and the way to get to happiness is to pick an evaluatable baseline.

Machine learning-based systems are typically also services in the backend of web applications.They are integrated into production workflows. But, they process data much differently. In these systems, we don’t start with business logic. We start with input data that we use to build a model that will suggest the business logic for us.

This requires thinking about application development slightly differently - we need to be able to loop through a machine learning inference cycle quickly and examine the results: are they right? If yes we keep the model, if no we go back and change one thing and move on.

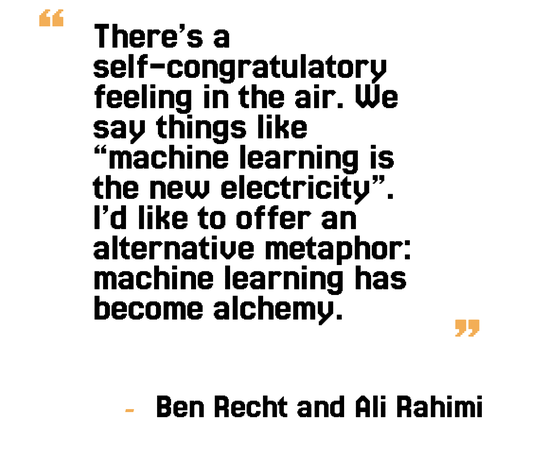

This means there’s a lot of trial and error. Not many people realize it, but machine learning is more like alchemy than even software engineering. The top people in the field even said so, as Ali Rahmi did in his NeurIPS keynote in 2017.

This is doubly true for LLMs, where our main medium of input and output is freeform text. We have some model that we add text requirements to, and hope to get back logical text, or instructions, or code out. Because the inputs of natural language are so varied and so are the outputs, the process becomes three times harder to control and evaluate.

What this means for focus is that the developer, like the monks, has to create a center of focus, and that center of focus is the first use-case for evaluation for your model. That means, if you’re a bank, you can’t evaluate a model on how well it writes poetry. It needs to be on how well a model creates top-level topics for all of your documents.

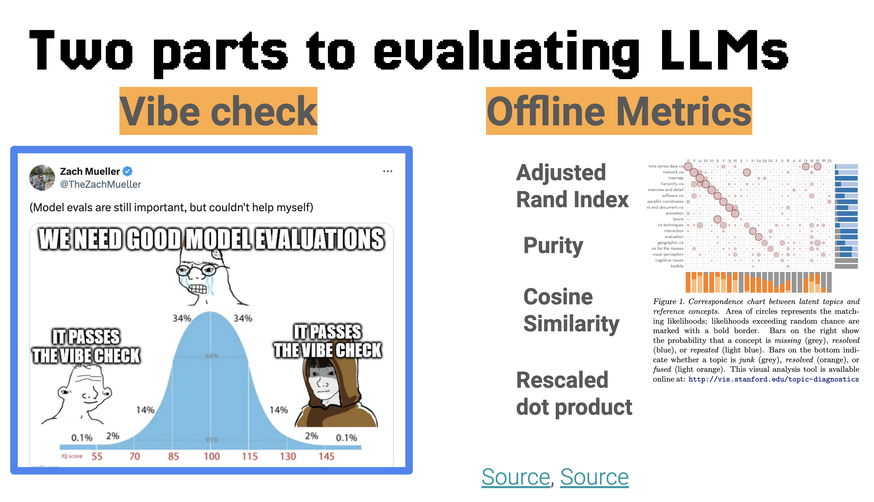

This means creating both what we call offline and online evaluation metrics. Online evaluation metrics are those that can be assessed by people using your product or platform, or simply doing what we call a vibe check, and offline evaluation is more scientific and offers us a grounded reference against academic benchmarks to see if our model generalizes well. In order to have a well-functioning machine

So the developers decided to look at two metrics:

- The vibe check

- The offline eval

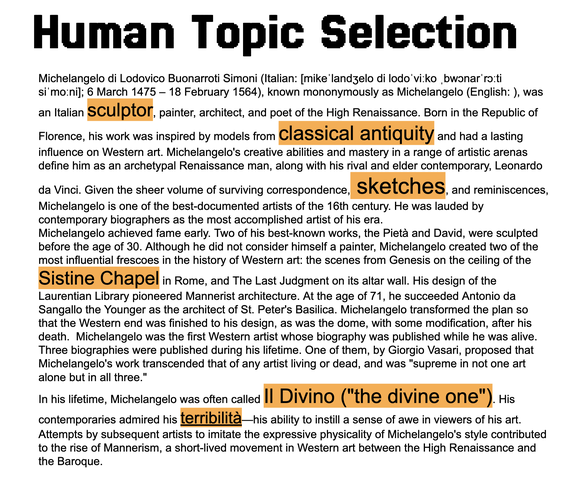

The vibe check is as simple as: creating a list of documents and manually labeling topics for these documents, for a number of different documents. Here’s an example from the wikipedia page for Michelangelo.

We can see that we added some human topics based on simply scanning the text and our knowledge of categories, as experts in art.

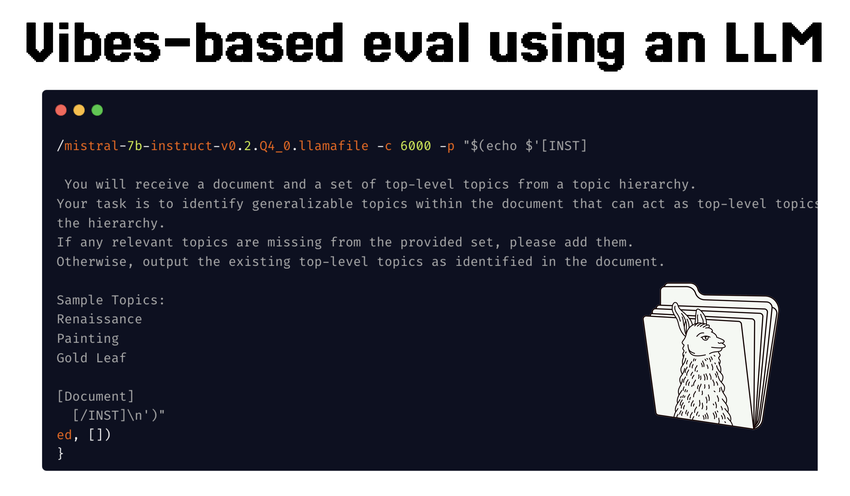

The comparison is now to run it against our LLM and see what topics it generates. We use llamafile locally, with a local quantized model for quick iteration between prompts and responses without having to use external models.

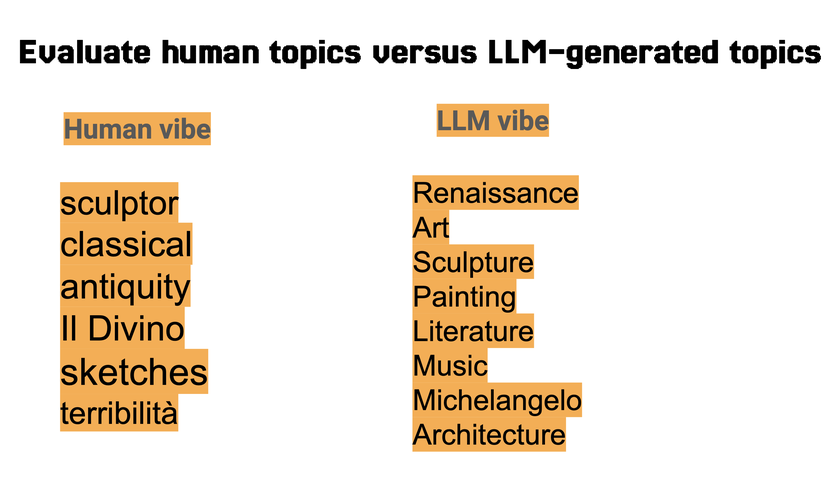

We can now compare the results we generated ourselves and what the model generates.

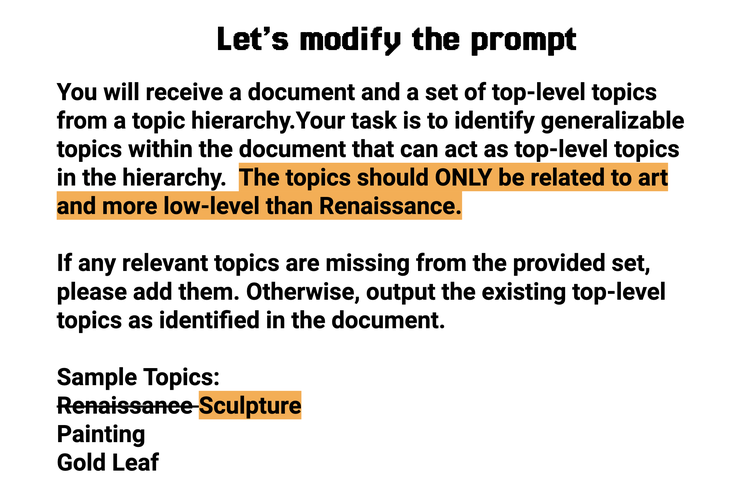

We can see the results are ok, but maybe not as low-level as we’d like? For example, “Renaissance” doesn’t help us at all since all of our artists are from the Renaissance. And literature is not a category in art. So our next step would be to modify the prompt.

We can do this kind of prompt tuning manually for a bit, or use automatic prompt-tuning libraries, but then we might find that our model itself doesn’t have enough information about art, in which case we might want to fine-tune it with samples of text specifically related to Renaissance art, and try again.

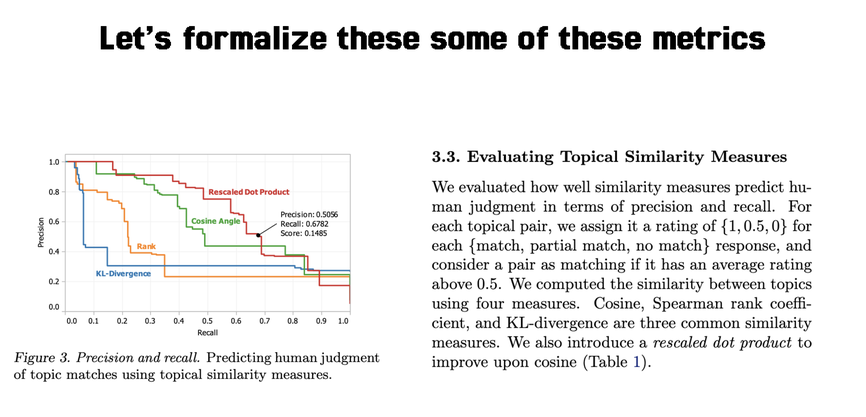

Once we go through this manual cycle, we can also perform offline metric evaluation, which allows us to more systematically evaluate the model based on agreed-up academic benchmarks. Topic alignment is an imprecise science because it’s based on what humans think are good topics for categories, but we can use metrics like cosine similarity to look at how well given topic pairs match.

Once the developers did this and tuned the model, the CEO was once again happy. But, now the team had a different problem, the curse of success. They needed to deploy this model to production.

Now, the team had a use-case for trending topic detection, and they had an evaluation metric: manual vibes and rescaled dot product for similarity between human-assigned and machine-assigned topics.

They had problems, though. The systems they were building were big and complicated. They now involved the model, and something horrible called LLM ops that now involved updating, monitoring the system, storing prompts, monitoring model output, monitoring latency, security, package updates. They had built a product with an LLM producing summarization inputs, but now, whenever something broke, they didn’t know where to look.

The Reproducible Example

So, on the final day, the final developer shared a story. He said, “This story is about Ellen Ullman. She was a software engineer who worked on complex systems starting in the late 1970s including at startups and large companies, wrote a number of essays about the art of practicing computer science. Her latest book is called “Life in Code”, and in it, she describes the mind of a programmer as they are writing a program. And this ties together everything we’ve been talking about so far.

She writes that keeping track of translation between human and code logic is hard. “When you are writing code, your mind is full of details, millions of bits of knowledge. This knowledge is in human form, which is to say rather chaotic. For example, try to think of everything you know about something as simple as an invoice. Now try to tell an alien how to prepare one. That is programming…To program is to translate between the chaos of human life and the line-by-line world of computer language.”

She says that, in order to do this, a developer must not “lose attention. As the human world-knowledge tumbles about in your mind, you must keep typing, typing. You must not be interrupted.”

In this kind of environment, you are information-constrained, but focused. It is harder to get through a mistake, but easier to find it and test possible solutions because the feedback cycle is fairly short. The reason this was the case was because, in earlier times, developers worked closer to the machine, closer to the metal, closer to the source of the computation, and even though there were interruptions and blockers, they were different.

Most programs were written and compiled locally in languages like C. There were much fewer third-party libraries. Implementations were written from scratch, and the main source of information were books, man pages, and Usenet. The approximate user experience would be similar to writing python by only being able to access python.org.

Ullman describes this phenomenon in another part of the book where she describes working with a developer named Frank. Frank previously had worked as a hardcore technical contributor, but when he was working with Ullman, he had moved to financial reports, and he personally was miserable, and he also hated Ullman because she was “close to the metal.”

These days, it is extremely hard to be close to the metal, because when we work with distributed systems, and machine learning, and the cloud, each of these have been built on top of the levels of turtles that previous developers have built, and it is easier to get distracted.When you throw non-deterministic LLMs and the distributed systems used to train and serve them into the mix, you come up with a special kind of hell that makes it impossible to have a good developer experience.

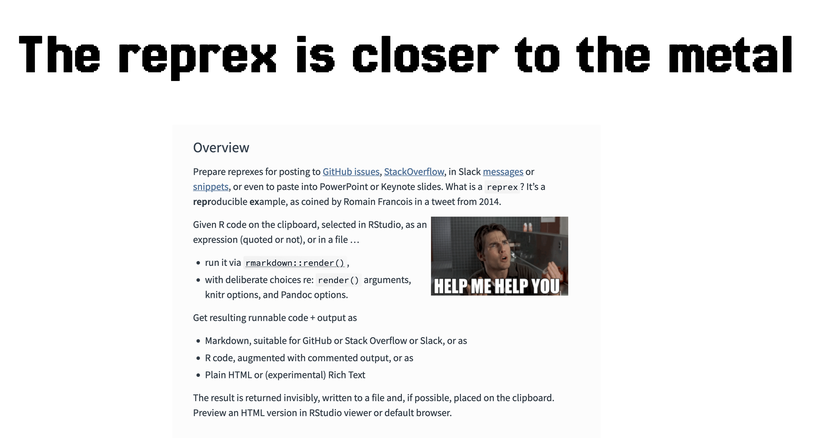

What we can do is what people have always done: create reprex. A reprex is a reproducible example, an idea that comes from the R community. In R, it’s fairly easy because it’s a self-contained piece of software, but we can also strive for the same thing.

Here’s an example of a reprex in Python, the RMSE code we just reviewed in the first section. We can know it will run the same way on our reviewer’s computer as ours, we can troubleshoot and check.

def root_mean_squared_error(y_true:float, y_predicted:float) -> float:

cost = math.sqrt(np.sum((y_true-y_predicted)**2) / len(y_true))

return cost

Reprex comes in handy when you’re dealing with complex distributed systems. For example, here’s an actual problem the developers were dealing with while trying to serve their model: trying to troubleshooting Ray.

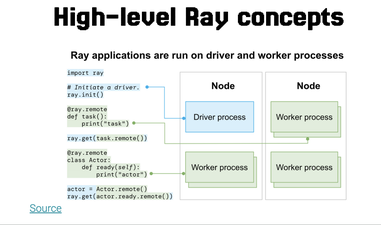

Ray is a Python and C++-based distributed framework for training and serving machine learning models, used by companies training LLMs. Its predecessors include Hadoop and Spark. It also takes inspiration from other distributed libraries. The cool thing about Ray is that it is very easy to run locally, and spinning up a single instance is something that comes out of the box, meaning we are already closer to the metal.

However, if you have an issue, it can take a while to get to the bottom of it because of how complex the architecture is. Ray has several orthogonal patterns working together. First, there are tasks that you can execute on a remote cluster and actors, which are stateful tasks. This comes from the actor pattern in computer science which receives messages from its environment and can send messages back.

We also have the cluster-level communication patterns, with the global control store managing transactions and if you are running this on top of Kubernetes, also the Kubernetes primitives there is also the Task execution graph, the various modules: the dashboard, ray train, and Ray serve. The amount of patterns you have to understand in order to wrap your mind around it is truly astounding.

But don’t forget that humans can only keep several things in memory when they trace through complexity!

In building their trending topic application, the team had an issue where they were looking to test a topic detection pipeline of their model using Ray serve. Ray Serve takes your local deployable code and ships it to your Ray cluster using the Ray client, which is an API that connects a Python script to a remote Ray cluster.

Ray Serve allows you the ability to serve a model with code that gets sent using bundled Ray actors known as deployments. A Deployment is served usually on top of Kubernetes, on top of Ray, within some sort of cloud cluster. It’s made up of several Ray Actors, which are stateful services run and managed by the Ray control plane. The Controller acts as the entrypoint for the deployment , tied to a proxy on the head node of a Ray cluster, and forwards it to replicas which serve a request with an instantiated model.

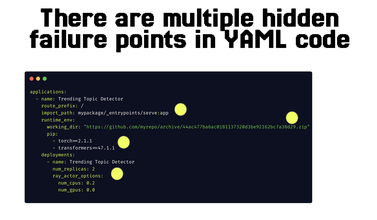

In order to serve a deployment, you can use the pattern of specifying a YAML-base config.

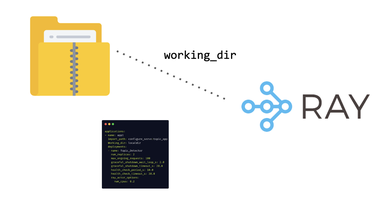

One critical piece here is the working dir, which specifies the where code to download to the cluster at runtime: This is part of how ray specifies the RuntimeEnv.

A copy of the working_dir will be downloaded to the cluster at runtime, and the current working directory of each remote Ray worker will be changed to that

working_dircopy

In a production-grade deployment, it’s recommended that the working_dir comes from a served zip executable, which is usually pinned to a hash in GitHub. So the team had their config file set up like this:

However, there are several points of failure in the YAML file, which looks to simplify but in fact hides complexity from us in the ways config is read and implemented in the code itself. But this model didn’t launch or run. Why? If you look at all the failure points, there are at least three or four that could trip you up. First, the way Ray handles import paths could be different behavior than the way we usually assume uvicorn routes them. Then, there is the question of the runtime environment: what happens when our deployable asset is hosted on github. Then, we have the issue of Python dependencies: when you’re working with fast-moving libraries like transformers and torch, it’s always guaranteed that you’ll have conflicts, sometimes even if you pin them to specific versions. Finally, there is the Ray deployment logic itself: what happens when we specify CPU and GPU options, and how do those work with our Kubernetes cluster?

Whew. Time to start debugging.

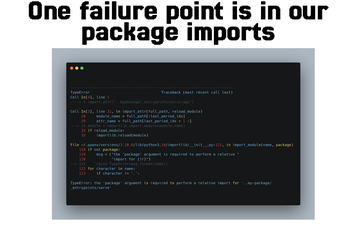

The way to start here is to start reading logs and stack traces. When you have a very large, distributed system, here’s a sample of the stacktrace you might get, and it can be very discouraging because it doesn’t point you to where the issue is.

There’s a lot going on here, and it seems to be coming from importlib rather than Ray itself, but Ray uses importlib as a dependency. So, in order to isolate it, the team went into the module in Ray that calls importlib, which lives in python/ray/_private/utils.py.

What the team then did was to find the method that opens the import path, and created a reprex for the issue, where they took that exact method calling importlib.import_module, put it into a notebook, and called the code directly.

This directly didn’t work, and they proved it without using any external dependencies or Ray itself - they found the source of the issue. Which meant that, in their case, they couldn’t use the nested path to build their model deployment, but for simplicity’s sake, they could serve it from the root level. It turns out that the issue was in the import_attr, which meant that they had to include the config file and the script to launch the cluster in the same root-level of the repository.

They weren’t done yet, though. When they tried to deploy this, they also got a 404 error when they tried to download the deployable from the Git hash. This is because they were trying to enable asset downloads, aka our Topic trend detection code, from a private GitHub repo onto the head node in the cluster for running the code. Initially, they tried to use a fine-grained PAT: This didn’t work, so they had to use a legacy GitHUB token. Along the way, they learned that Ray uses a library called smart_open for streaming files from S3/GitHub, which helped them troubleshoot further issues.

All of this is abstracted away from us by the YAML, quickly-changing documentation, and multiple parts of the system. To get from that to the piece of information you need, the team needed to ruthlessly strip out all areas of detail and focus on the problem, and, hopefully, get to a reproducible example. This is getting closer to the metal, this is attention.

Finally, the team had a prototype running in production. With this issue resolved, the team moved on, and was successfully able to deploy the topic detection app, much to the delight of the CEO. Everyone got raises and lived happily ever after in their own castles in Florence.

Until they started to develop more products.

Conclusion

The developers celebrated. They had launched something into production, managed to cut away from the hype of the LLM space, and focused on a use-case that was important to their company.

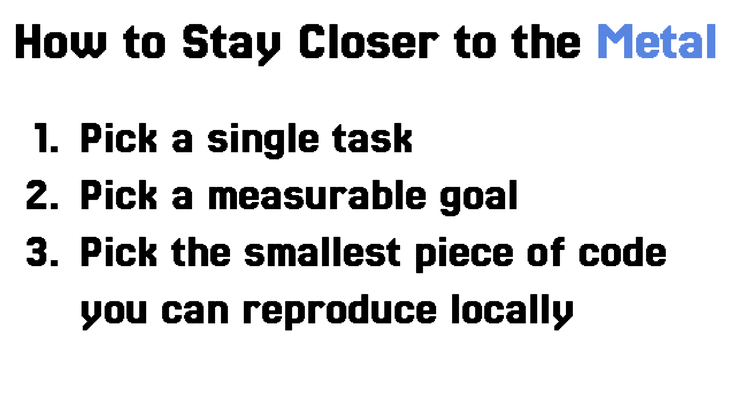

They now came together to do a retro on what they had accomplished, and why they were able to do so. They started by picking a single use-case for generative AI in their application and evaluating the models available for that use-case. Then, they picked online and offline evaluation metrics to continue the evaluation loop. Finally, when it came down to building the system, they focused on the smallest composable parts possible instead of starting with the top, and broke down the code until they understood it.

All of this helped them concentrate, focus on what was most important and stay close to the metal.

Thanks to Davide Eynard, Guenia Izquierdo, James Kirk, and Ravi Mody for patiently reading versions of this talk.

Credits

- Icons: Freepik

- Bronzino, Portrait of Eleonora of Toledo, c. 1539

- The Decameron, Franz Xaver Winterhalter 1837

- View of Barcelona, by Anton van den Wyngaerde, 1563

- Gradient Descent

- Gradient Descent