The beginning of wisdom is to call things by their right names

I was nameless for two weeks after I was born. My mom and dad hadn’t decided on a name beforehand, and didn’t bother to consult the ultrasound. There was no ultrasound in Russia. Just, maybe, if the mom’s stomach was more eliptical than round, it was probably a boy. And if the doctor sacrificed a sheep under the light of the moon and the entrails leaned to the right, then, most likely a girl.

Anyway, so after I was born there were Intense Party meetings, mostly between my dad, my mom, and my grandma, my mom’s mom.

“I want to name her Svetlana. Or Alisa (Alice),” My dad said.

“No,” said my grandma. That was the meeting.

The conflict went on for two weeks and I was just referred to as “she,” kind of like Cousin It, but only fatter.

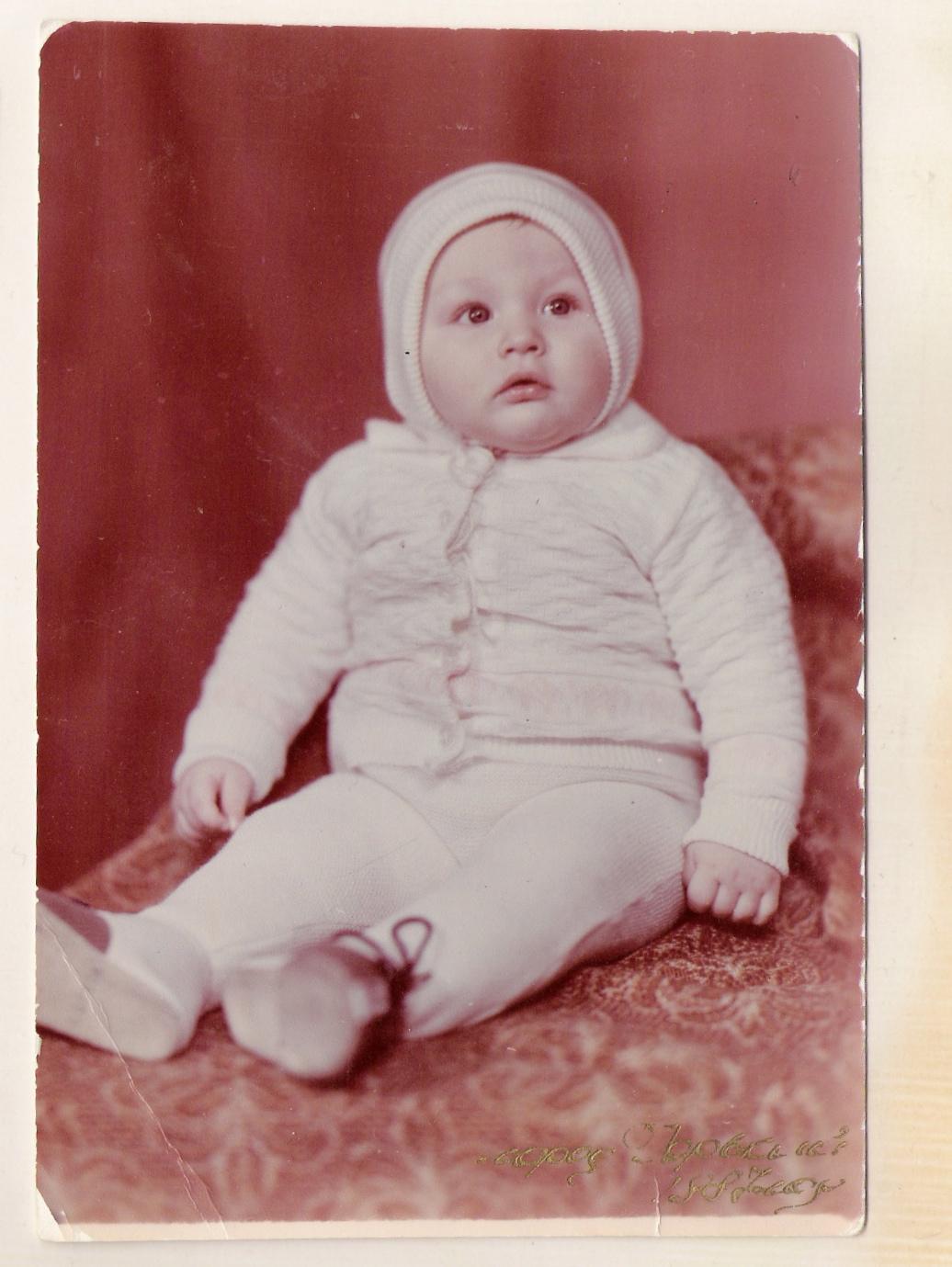

I was so fatty I couldn’t sit upright for the first couple months. Part of this fatiness was because in Russia, it was important to keep feeding a child until they couldn’t take anymore. Because a fat child was a healthy child in a country run on 5-year plans, where food never seemed to actually be in the plans. So the constant feeding was kind of like love waterboarding. By the time I was 2, I was the size of a baby hippo. “She looks so good,” my grandma, born in WWII and understanding famines, complimented my mom. My mom beamed.

My dad said, “What about Victoria?”

My grandma brightened up. Vika is the Russian nickname for Victoria and she just happened to have a breed of strawberry growing at her dacha nicknamed Vika. Also, Vika rhymes with klubnika, which is strawberry in Russian. It was perfect! My father scratched his head. He’d gotten the name from some novel and remembered it and liked it. He didn’t remember which one.

Others in my family were still kind of liking Svetlana, but my dad stuck with Victoria.

Years later, when we immigrated to America, all the Svetlanas, Nadezhdas, and Tatiyanas suffered. At immigration, they struggled to Latinize their names, which with specific cadence and intonation, just didn’t fit into English, the way you can’t just cram a $500 Gucci dress into your cheap $20 suitcase.

I stayed Victoria at first. But even in first grade, it became too pretentious for me. While other Russian Viktoria, Viktoriya, and Victoriyas and wore their strange permutations with pride, I was uneasy. It was too big of a name for me, too majestic, too Soviet for a time when I just tried not to be noticed as the weird kid out in my American school, even though it was still an English name.

“Victoria, can you solve this problem?” Mrs. Gray called on me.

“Can you call me Vicki,” I said.

“Sure, Vickie,” she said.

But I definitely knew I wasn’t a Vicky, Vickie, or a Vikki. I was a Vicki, plain and simple, with the least letters. It was easier that way in English to normalize.

At home, I was still Vika, Vikachka, Vikanka, Vikushenka, Vikusenka (my dad’s name for me,) and dochenka (diminutive for daughter.)

But at school, I was Vicki. And as I grew older, I found that I didn’t want to go back to Victoria. I’m still pretty uncomfortable with it. I don’t think anyone I know has ever called me Victoria. I keep hoping someday I’ll grow into it.

Stay tuned for a second part where I painfully detail how I screwed myself over when I chose my Hebrew name. Bonus points if you know what it is.