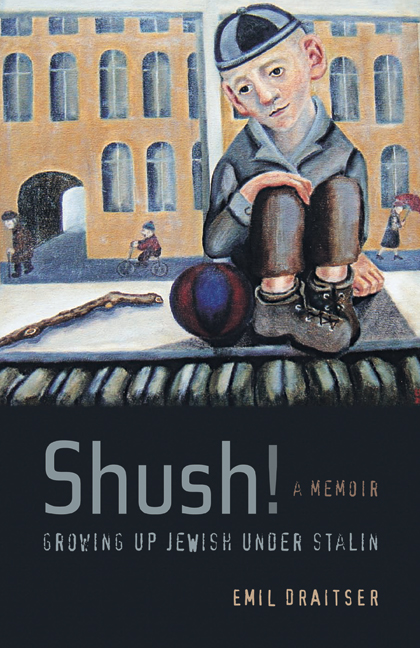

Book Review: Shush! Growing up Jewish Under Stalin

Have you ever read any books that perfectly articulate how you see the world? Books that you can show to your friends when you don’t feel like explaining your life view and say, “Here, read this, and you will understand me?” Shush, A Memoir-Growing up Jewish under Stalin by Emil Draitser, is such a book for me.

There are a couple of books that really explain what being Russian/Jewish is all about: From Lenin to Lennon, Sashenka, and The Russian Debutante’s Handbook, which is written by one of the writers that I deeply look up to and plagiarize try to imitate in writing style, Gary Shteyngart.

They all have slightly different takes on growing up Jewish in the Soviet Union. This one is the closest to what my grandpa has so far told me of life back then. It also explains several questions people often have about Russian Jews: Why are we not religious? Why don’t we have Russian names? How were we mercilessly targeted by the Soviet authorities? And how are Russian Jews different from Russians?

This book explores all of those themes, particularly the dichotomy of “us” and “them.” The overarching theme of this book is how Emil (nee Samuil) Draitser grew up imbued with Soviet propaganda and a constant fear of anti-Semitism that distanced him from his Jewish relatives. He only discovered the positive aspects of being Jewish after he immigrated to America when he was 37. He first noticed and started exploring this topic when an academic friend of his mentioned that he spoke at a lower volume whenever he said the word “Jew.”

This piece of information is hardly surprising to anyone growing up in the Soviet Union and even Russia today. As a Jew, you were constantly put on alert and denigrated in ways that are hard to imagine living in America. “The Jewish problem” was mulled over both by Soviet officials and the common drunkard at bars.

As Draitser writes, it was so bad that he was constantly looking over his shoulder and disassociated with any Jews in his family, changing his name from Samuil to Emil to seem more Russian. This was a common phenomenon. In this same way, my grandfather Zalman became Evgeniy and my grandmother Sarra became Soniya. Their last name of Gorivodsky was still suspect, but not as bad as, say, Rabinovich, who is the archetypal but of all Russian jokes against Jews.

It’s so bad that even I, brought up mostly in America, still have a stigma about saying the word Jewish to non-Jewish Russians. For example, if I’m meeting someone Russian I don’t know, I’ll never bring up that I’m Jewish unless it’s mentioned. I’m not embarrassed to be Jewish in America, but with Russians, it always seems different. Like I’m afraid they’re going to pogrom me in five minutes. Or offer me a deal on an illegal Chinese cell phone at the very least.

There is always the mentality among Russian Jews that anyone seen doing anything distinctly Jewish is a sucker. Obviously this has faded with life in America, but I was surprised while reading this book at how many of these feelings are still active in me and how they have been developed over several generations.

Even if you’re not a Russian-born Jew raised on dranniki (latkes), pogroms, and Mikhoels, I think you’ll enjoy this book to get a perspective at a unique time in history (Odessa during Stalinism) and someone who maps out very well how he finally reconciles his identity. Draitser really strives and succeeds in recreating the Odessa of his childhood for you and along the way traces the steps of how he is slowly indoctrinated into a Soviet viewpoint, and how he slowly , with help from his family, regains his Jewish heritage. [Insert pithy post-WWII Yiddish phrase here to end the review.]