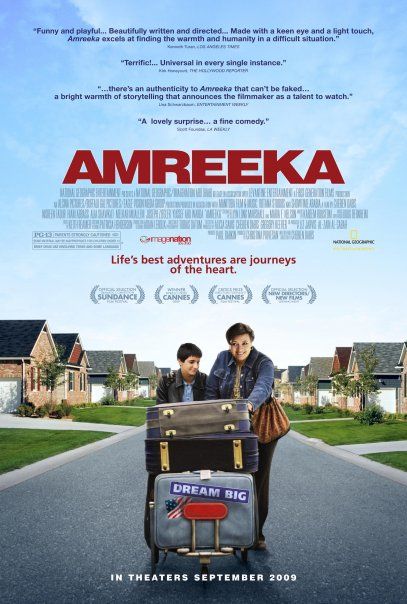

Movie Review: Amreeka

Go see this movie. As soon as possible.

Amreeka (America in Arabic) is the story of how a Christian Palestinian single mom, Muna, and her son, Fadi, get a visa to go to America from the West Bank town of Bethlehem because it is clear that there is not much future in the territories for them. They arrive in snowy Illinois to stay with Muna’s sister and her family. So starts Muna’s process of getting on her feet as an immigrant by working at White Castle (having obtained two degrees and 10 years experience working in a bank), and Fadi’s process of fitting in at his new high school.

I’ll let the trailer speak for itself:

Everything about this movie was achingly familiar and close-to-home for me, both in the scenes they shot in the West Bank and the ones in America.

I’ve been struggling lately with reconciling my Zionism with the realization that Israel is not only a place of ideals, but a country, just like any other, where ordinary people get up, go to work, drink Aroma coffee, and are screwed over by the beauracrcy of what is ostensibly a state created to protect us. The fact that Israel, even as a Jewish state, is not perfect, has caused me to struggle between loving it and criticizing some of its actions.

In spite of this inner conflict, the minute Israel and the territories were shown in the movie, I became “homesick”. The director, Cherien Darbis, portrays Israel and the territories with much familiarity. All the nuances: the pale Jerusalem stone, the small, hot, cramped makoliot with flies on the tomatoes, the constant sunshine, and the crowded markets. However, Darbis takes all of these things that I am intimately familiar with, and spins them on their head. She doesn’t show Israel proper. She shows Bethlehem, the separation wall, and the checkpoints. She shows Palestinians living their everyday lives, and she shows it from their perspective. True, there is a political tilt, but, for the most part, she just aims to show how Muna and her family live, particularly as non-Muslim Palestinians that have to put up with the same obstacles as Muslims (who are, ostensibly, responsible for 100% of terrorist acts commited in Israel) do.

All of a sudden, everything changes as Fadi pushes Muna to accept the visa. They fly to Chicago and brought home to live with Raghda, her husband, and their three children in American suburbia. And this is achingly familiar, too. The comfortable suburban houses, the American road signs, the snow, and small-town life. Raghda’s children, mostly born in America, are predictably enormously Americanized and look at Muna and Fadi with wild eyes. They reply in English to Muna’s Arabic and blast rap music. They sneak out of the house to smoke weed and, what’s most important, the eldest daughter argues passionately about the rights of Palestinians without really understanding what it means to be one.

I really loved this movie because of the way it portrayed immigrant life (with the same type of flavor as My Big Fat Greek Wedding, but slightly more serious.) It once again reaffirmed my belief that all immigrants are the same. Our parents have the same fears that their children will assimilate, that they won’t carry on the traditional cultural mores that they’re used to, that they won’t speak their native language. At the same time, they know America is really the best place. Yet, they still have nostalgia. One scene really stuck with me. Raghda and Muna are in an Arab grocery store, and Raghda says something to the effect of, “Oh, how I want to go back to Palestine. The food tastes better there,” and Muna replies that everything has changed in the 15 years they’ve been away; the wall is in place now, and the people are much different. Raghda replies, “It doesn’t matter, it’s still home,” and Muna replies that there’s really nothing left there for them. This struck such a deep chord with me because the nostalgia, the urge to return, forgetting everything else, is one that is also very prevalent in the Russian community. It also clearly shows the difference between Americanized immigrants and those fresh off the boat, and the sharp difference in family values.

More than relate the immigrant story, Amreeka also humanizes Palestinians, bringing them down from suicide bombers or casualties in the far-away headlines, to real people. They live in Bethlehem, a town that’s in the news a lot, but which we don’t see a lot of in real life. They laugh, they dance, they are angry, just like normal people. They’re not all oppressed wretches, and they’re not all Al-Aqsa suicide bombers, just as not all Arabs are Iraqi and deserve to be shunned. Some Arabs, such as everyone portrayed in this movie, aren’t even Muslim. How do they fit into the web of stereotypes that we construct?

All in all, the honesty, warmth, and genuine hope in this movie make it a must-see for anyone, either to understand Palestine beyond the politics, or to understand immigrant culture in America. Jews and Zionists, this goes double for you. It challenged and broadened my understanding of Palestinians as a people, and I hope it will challenge yours, too.