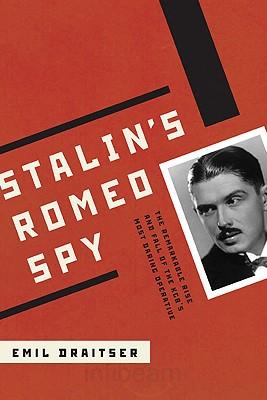

Book Review: Stalin’s Romeo Spy

(Full disclosure: Book provided for review by Northwestern University Press. Lots of spoilers below, but I think this book is more about the journey than the ending, so read on. Old time-y Pictures of Russia in the 1940s/50s/60s in this post from here__. )

When I was in Moscow with my dad four years ago, we went to see waxy Lenin rotting away and, afterwards, walked along the walls of the Kremlin, where many current and former Soviet military leaders are buried. As the drunk tour leader waxed on and off about the Russian military, one Russian man asked, “And where is Iosif Vissarionovich? I’d like to pay him a visit, and thank him for organizing the country,” using Stalin’s patronymic as a form of deep respect.

I didn’t think anything of it at the time because Russians often grumble about how everything was much better under Stalin’s rule, the same way Americans sometimes think that Andrew Jackson brought order to the country or that the world thinks that China’s economic stability policies balance out its human rights record. But, recently, Stalinism worship has been on the rise.

There’s [(Full disclosure: Book provided for review by Northwestern University Press. Lots of spoilers below, but I think this book is more about the journey than the ending, so read on. Old time-y Pictures of Russia in the 1940s/50s/60s in this post from here__. )

When I was in Moscow with my dad four years ago, we went to see waxy Lenin rotting away and, afterwards, walked along the walls of the Kremlin, where many current and former Soviet military leaders are buried. As the drunk tour leader waxed on and off about the Russian military, one Russian man asked, “And where is Iosif Vissarionovich? I’d like to pay him a visit, and thank him for organizing the country,” using Stalin’s patronymic as a form of deep respect.

I didn’t think anything of it at the time because Russians often grumble about how everything was much better under Stalin’s rule, the same way Americans sometimes think that Andrew Jackson brought order to the country or that the world thinks that China’s economic stability policies balance out its human rights record. But, recently, Stalinism worship has been on the rise.

There’s](http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/02/11/AR2006021100845.html) and tons of proof. There are constant May Day marches with Stalin as the key personage being glorified. There are images of Stalin in the Moscow metro. In their constant struggle to turn their screwed-up country into one incorporating some kind of stability, Russians forget that Stalin murdered ruthlessly, precisely, and constantly and that millions and millions of lives were ruined with a single phone call.

That’s where Emil Draitser’s [(Full disclosure: Book provided for review by Northwestern University Press. Lots of spoilers below, but I think this book is more about the journey than the ending, so read on. Old time-y Pictures of Russia in the 1940s/50s/60s in this post from here__. )

When I was in Moscow with my dad four years ago, we went to see waxy Lenin rotting away and, afterwards, walked along the walls of the Kremlin, where many current and former Soviet military leaders are buried. As the drunk tour leader waxed on and off about the Russian military, one Russian man asked, “And where is Iosif Vissarionovich? I’d like to pay him a visit, and thank him for organizing the country,” using Stalin’s patronymic as a form of deep respect.

I didn’t think anything of it at the time because Russians often grumble about how everything was much better under Stalin’s rule, the same way Americans sometimes think that Andrew Jackson brought order to the country or that the world thinks that China’s economic stability policies balance out its human rights record. But, recently, Stalinism worship has been on the rise.

There’s [(Full disclosure: Book provided for review by Northwestern University Press. Lots of spoilers below, but I think this book is more about the journey than the ending, so read on. Old time-y Pictures of Russia in the 1940s/50s/60s in this post from here__. )

When I was in Moscow with my dad four years ago, we went to see waxy Lenin rotting away and, afterwards, walked along the walls of the Kremlin, where many current and former Soviet military leaders are buried. As the drunk tour leader waxed on and off about the Russian military, one Russian man asked, “And where is Iosif Vissarionovich? I’d like to pay him a visit, and thank him for organizing the country,” using Stalin’s patronymic as a form of deep respect.

I didn’t think anything of it at the time because Russians often grumble about how everything was much better under Stalin’s rule, the same way Americans sometimes think that Andrew Jackson brought order to the country or that the world thinks that China’s economic stability policies balance out its human rights record. But, recently, Stalinism worship has been on the rise.

There’s](http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/02/11/AR2006021100845.html) and tons of proof. There are constant May Day marches with Stalin as the key personage being glorified. There are images of Stalin in the Moscow metro. In their constant struggle to turn their screwed-up country into one incorporating some kind of stability, Russians forget that Stalin murdered ruthlessly, precisely, and constantly and that millions and millions of lives were ruined with a single phone call.

That’s where Emil Draitser’s](http://www.stalinsromeospy.com/) comes in.

After I’d reviewed Draitser’s last book, his memoir, Shush! Growing up Jewish under Stalin, he let me know that he was about to publish another book, this time a biography, of a Russian spy. This was months before the current scandal, and intrigued, I read the book. It was not at all what I expected it to be; that is-a light-hearted look at the Soviet spy system. Instead, it is a systematic examination of a single life, how life fits into the Soviet system, and the dangers of erasing history, which is where the Stalinist worship comes in.

The book is about Dmitri Bystrolyotov, a KGB operative in Prague, London, and many other European cities, about his professional life, his personal life, and his struggles against the Soviet government he loved. It plunges immediately into his excruciatingly hard childhood and the life that led to him becoming wholly devoted to the Soviet regime as he grows older and continued to serve the state. His mother was a very early feminist and decided to experiment with having a child without a husband. Subsequently, she abandoned Dmitrit, as did his “father”, and these abandonment issues plagued him his entire life.

Bystrolyotov’s most recent official biography makes light of the fact that while he was growing up he saw his parents rarely. To begin with, this statement is misleading. He “rarely” saw only one of his parents-his mother. And he never ever saw his father, a situation that deeply wounded him and to which he returns again and again in his memoirs.

This situation is important because, as Bystrolyotov returns to it, so does Draitser. In fact, the first part of the book, which details how Bystrolyotov leaves his hometown of Anapa, joins the Russian navy, and hides out in Istanbul during the Russian Revolution. The book goes into excruciating detail about how he survives Istanbul, awash with destitute Russian refugees at the time, and makes his way to Prague, where he is recruited by the Soviet trade mission to start with small spying missions and eventually becomes a key member of Soviet intelligence.

To be honest, the first part of the book was painstakingly slow for me, even though it does include really great detail about World War I, mostly because there is so much psychoanalysis of Bystrolyotov’s character and his motivations for doing some of the things he does. it took me a long time to get through this part, mainly because I don’t enjoy books with a constant stream of inner monologue.

In an e-mail interview, Emil Draitser reveals that there is a reason it is so:

I’ve written and published many fiction stories where I was in total control of characters. In this non-fiction book, I had no option but to stick to the facts at hand. I didn’t change any of them even one bit. But Bystrolyotov’s own behavior during a few points in his life was so bizarre that I had to resort to help of professional psychoanalysts to understand him. That’s why, in some places, I had to slow down my narrative pace. I felt that I need to convince the reader to accept highly unusual actions of my protagonist.**

Although it is true that the psychoanalysis helps, it makes it hard to get through the first part, where every one of Bystrolyotov’s actions from the time he is born until the time he leaves the spying game for Russia is analyzed and put into a psychological context.

But it’s incredibly worth it, just to get an exclusive peek into the lives of Soviet spies operating abroad. For example, here’s a case where he had to impersonate a Greek merchant:

Getting a legitimate passport was only the first step in creating an operative base in a foreign territory. Now Dmitri had to come up with numerous details to make his assumed personality blend with the surroundings. Here one could not be too careful. As Dmitri told the writer in the course of our interview, ‘if you pose as a herring salesman, you should be able to tell one herring from another.’ “

His intrigues soon became more and more dangerous, and the book describes him as gallivanting around Switzerland, England, Italy, and Germany during the political tension predating World War II. The descriptions of the spy work is exhilirating, even if the descriptions of his constant mental state are not.

The second part of the book is more serious and relates to Stalinism directly. Conflicted between the duties of spying that constantly break his moral boundaries: i.e.- sleeping with women high up in diplomatic European circles to get information, lying, always on the brink of killing, and never being able to let his guard down, Bystrolyotov decides to stop being a spy and go back to Russia. At this point, I asked why he didn’t just defect to the West. The author answered,

The first generation of Soviet spy were preoccupied with the idea of promoting Communism as the best hope for humanity. Like Bystrolyotov, they were all totally devoted to it because they sincerely believed in it. Therefore, very few of them defected before Stalin came to power.

After that, a few of them (Walter Krivitsky, Alexander Orlov, Ignacij Reiss) defected to the West not because they were seduced by comforts of Western life, but because they saw that Stalin replaced the idea of the world revolution with dictatorship and blind obedience, with personal loyalty to him. Like many others, these spies would be shot upon return.

Continuing to be loyal to Stalin and the Soviet Union, Bystrolyotov returned to life in Moscow with his wife, just in time for the purges to really go full-blast, particularly to eliminate the old guard of spies that had grown up under Lenin, of which Bystrolyotov was a part.

I’ve read about the imprisoning and shooting in many books, including Shashenka and Gulag Archipelago, but the description is raw and hard to read every time. Draitser writes,

Now, Dmitri found that anticipating arrest was torture in itself. He lived with his wife and his mother in…Sokol, on the Moscow outskirts, in a building occupied by NKVD employees. Every night, black Marias (the nickname for the cars that took arrestees to their prison cells) rolled up to the building. It was impossible to fall asleep.

Eventually he succumbs to the pressure and, through a false misstep, is arrested. So begins his time as a ghost in Soviet society, starting with beatings and breaking him down mentally, and ending with almost twenty years of hard labor in Siberia. This part of the book is extremely hard to read because it is so moving, and, coincidentally, is the best part. The author writes,

His physical suffering was exacerbated by excruciating loneliness. Most of the time he remained alone in his cell, having no one to share his feelings with. Prisoners had to clean their cells themselves, and, one day, while washing the floor, he discovered a small cavity in it. He poured some tea and crumbs of bread into it and planted a small chunk of onion with roots in the little pit. Soon the onion yielded its first green sprouts, and Dmitri felts as if he owned a little garden with a living thing, which became his companion.

This part nearly broke me. Bystrolyotov was originally a powerful man, free of international boundaries and switching countries left and right, with the authority to kill, to find out information, to reason on his own. And Stalin reduced him to nothing, to less than nothing, in caring for a plant. What follows is worse-his time in Siberia, including hard labor both outside and using his skills as a doctor and translator.

And then, after you think you can’t read any more, he is released and the state refuses to recognize his service because he doesn’t have the proper papers. He was shuffled from apartment to apartment Bystrolyotov died anonymously.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union the post-KGB FSB started glorifying him and, today, there are at least two official biographies of him. The scary part is that his entire time in Siberia is completely glossed over.

Here’s where the Stalinism comes in. The author wrote the book, first, to explore the life of this amazing man, who he himself had a chance to meet in Moscow in the 1970s. But second, Draitser hopes that

** the book makes it clear the inhuman nature of Soviet system, which, while proclaiming its intention to make happy all humanity, was oblivious to any individual human life, in this case, the life of a Russian patriot who gave everything he had for the sake of his Motherland. **

I’m really hoping that this book is translated into Russian and starts making waves if it hasn’t already. It’s too important not to, in an era of Putin, of revisionist school history books that glorify Stalin’s role in World War II (which included placing Russian troops behind the actual Russian troops to shoot them if they retreated) of puppet presidents, and an era where democracy is viewed (by many of my family members and my parents’ friends in Russia) as “something for the United States; we do things our special way here in Russia.”

However, while the book is an excellent warning against repeating history and revising it, as the author puts it,

There are many more lessons to be drawn from this life story. This is also a story about the life-long damage of parental neglect, about the power of human spirit and the power of true love.

Buy it on Amazon here.