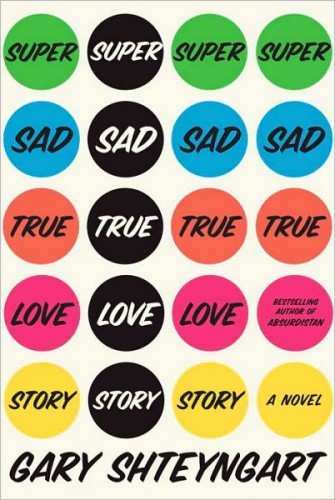

Book Review: Super Sad True Love Story by Gary Shteyngart

The phrase,

The Marines are at war, America is at the mall

doesn’t have a more relevant application than as the summary of Gary Shteyngart’s Super Sad True Love Story. I wrote before about how I thought he jumped the shark and that if I had to read one more story about the type of Russian Jewish guy my parents tried to set me up with-schmucky, directionless, and still at a mental age of eight, I would break up with Gary hard.

And this is me we’re talking about. Remember, I have a poster of Shteyngart that I sacrifice small lambs to in case the talent god ever decides to grace my doorstep the way he did G’s. I’m happy to report that the book and my beloved Gar-bear surpassed my expectations yet again and had me dog-earing every page with an urgent, “Remember this. It’s really poignant and clever.”

The book’s major premise is a combination of 1984, mixed with Brave New World, a bit of Shalom Aleichem, and the same deadpan jabs at our vapid American hyperculture that Shteyngart delivered at ex-Eastern Europe in his last two books (which I consider my personal Tanakh.) We are again in Gary’s beloved New York City, ten or fifteen years into the future, and all the recessionary trends that I’ve been tracking with alarm at work the past two years have been bloated and taken off as if they were on speed.

The U.S. is even more in debt to China, there is the regular (worthless) dollar, the yuan-pegged dollar and the euro-pegged dollar. Something called the American Restoration Authority scares the hell out of everyone by doing the opposite of restoring and instead installing military checkpoints to get in and out of America but especially the island of Manhattan. Their slogan, which I can’t get over, is “imply and ignore,” as in implying consent at their messages and pretending to ignore that they exist.

Everyone walks, receiving data streams from their smartphone-like apparati (a word which in Russian means ‘device,’ or, more precisely, ‘thingy’,) constantly “verballing” or “streaming” video or shopping with inflated dollars at stores like AssLuxury and Onionskin for nippless bras and translucent jeans. No one produces anything physical of value, and there are the intentionally vague and ominous career choices of “Credit,” “Media,” or “Retail.”

If this all sounds vaguely familiar, it’s because it’s just a funhouse reflection of the world we live in, reflected back with razor-sharp wit.

This is the backdrop against which the narrator, a one Lenny Abramov, woos a slight Korean first-generation beauty, Eunice Park (in a storyline I just found out was a huge case of art immitating life). Everything about Lenny’s Russian Jewish typical awkwardness and Eunice’s sharp, prickly Asian beauty is stereotyped and amplified so that even if you know nothing about these two sub-cultures you can relate. The genius is not only in the humor aspect, but the examination of a relationship that looks good on paper but really isn’t meant to last longer than a ping from an apparat data stream. Eunice is one of those 20-year-olds: ADHD all the way, but still reliant on her parents and nuclear family for a semblance of balance in her aimless life. Lenny is also aimless but because he is ANCIENT (almost 40) and afraid of both death and youth, he is more to be pitied than to be empathized with.

As a Russian Jew chick, I feel vaguely uncomfortable with the spot-on descriptions he offers of our kind: argumentative, unrepentantly racist, and a bit stereotypical. Unfortunately, he is correct on all counts. I’ve found in my own adventures in Russian Jewlandia that there tend to be two types of Russian Jewish guys: quiet and stable and smart, and, as he describes Lenny, schmucky, still traumatized by childhoods that the rest of us came out of just fine and completely unable to man up in any sort of Russian way. His books are always about the second and this type can never get over how American and in-tune with his feelings he is. Good thing he hasn’t delved into the first because that leaves some niche material for my first novel.

However, there is a lot to love in this book, even if you feel that Shteyngart is trying too hard to stay ahead of trends and maybe at times sacrificing substance for schtick. What’s most important for me is that he transcends the immigrant experience in this one to discuss broader themes.

If you’ve read it, I’d love to discuss. Ping me.