Chinese Mothers and Russian Mothers Go Together Like Mao and Stalin (When they Were Besties, not before they had a falling out)

I have no children, so I am obviously a parenting expert. And my parenting expertise tells me that Amy Chua, of the Mao Disciplinary Style Chuas, is onto something I’ve been struggling to articulate when talking to American-born friends about my upbringing. In her humblebrag post, “Why Chinese Mothers are Superior,”, designed to engineer enough controversy to ensure a reasonable first printing of her book and dibs on 4-star hotels at a future book tour, Chua outlines Chinese parenting techniques and delineates them from Western ones with a few bullet points that I found particularly relevant to my own experiences of being parented by immigrants:

- What Chinese parents understand is that nothing is fun until you’re good at it. To get good at anything you have to work, and children on their own never want to work, which is why it is crucial to override their preferences. This often requires fortitude on the part of the parents because the child will resist; things are always hardest at the beginning, which is where Western parents tend to give up.

- Chinese parents can order their kids to get straight As. Western parents can only ask their kids to try their best. Chinese parents can say, “You’re lazy. All your classmates are getting ahead of you.” By contrast, Western parents have to struggle with their own conflicted feelings about achievement, and try to persuade themselves that they’re not disappointed about how their kids turned out.

- Second, Chinese parents believe that their kids owe them everything. The reason for this is a little unclear, but it’s probably a combination of Confucian filial piety and the fact that the parents have sacrificed and done so much for their children.

Many of the same techniques that Chua used with her own daughters were ones that I and plenty of other Russian immigrant children were (and are currently) subjected to, making me think that Chinese mothers and Russian mothers are working in some sort of Communist bloc pact to turn out healthy adults that understand their roots.

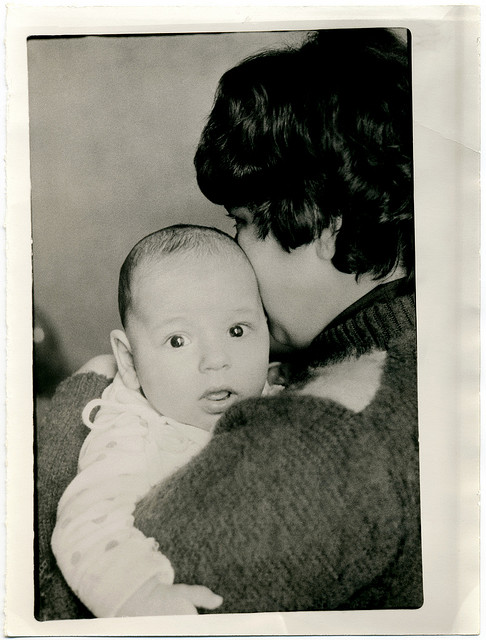

I and my fellow Russian immigrant children were not so much encouraged to play musical instruments (although I did, on my own initiative, take up the clarinet and later the piano, much to my parents’ disappointment,) but we were encouraged, constantly, to drive and succeed, because our parents had put “vsiu svoiu krov,” all of their blood, into first raising us as little kids in a country that had no diapers, no washing machines, no cars (unless you were really rich or really connected,) no food, and no toys. The constant stories about how our parents raised us in absence of first world benefits would drive us into deep morasses of guilt from which we would emerge only with 4.0 GPAs. One particular favorite of my mom was reminding me how she would take 45 minutes to bundle me up so we could go outside and walk kilometers to the nearest store to stand in line for food. On the way back, she frequently found that the elevator in our building was out of order and she would have to cary Baby V plus packages of groceries up nine flights of stairs, in the winter.

Once they got us out Russia, a guilt tactic was explaining to us in detail about how hard it was for them to emmigrate and leave everything behind, and that we couldn’t disappoint them since they had made a huge sacrifice for us. More importantly, we were not allowed to disappoint ourselves. We were not just representing who we were in school, but also our families and our culture. Oftentimes, it was the moms that drove this crusade, relentless, neverending, of making sure we had good grades, making sure that Russian/Jewish last names always showed at the top of the list, making sure we contributed to the household, and grew up to be decent human beings.

On top of the guilt, we also had the unfortunate pleasure of often being the children of the highly-educated. Although they were, in the difficult early years of immigration, hotel desk staff, pizza drivers, fast food cooks, nannies, and house cleaners, our parents, for the most part, were efficiently educated by the excellent Soviet system. In their past lives, they were economists and physicists, accountants and academics. Even if they weren’t, the Soviet system was such that someone with a high school education knew more than a 4-year college graduate in the United States. (My parents were frequently surprised at how we never read Theodore Dreiser in school and how I’d never even heard of him.) So they pushed and they pushed and they pushed.

I was horrible at math (still am). Unluckily for me, my mom has a Master’s in Math and Computer Engineering and, all the way up to 10th grade when we got to derivatives and she started to forget how to do certain things, we would sit together and parse out why I made mistakes, an exercise that oftentimes resulted in tears because I hated the way my mom explained things to me. Eventually, after working through countless problem sets and books from the library starting from third grade on, I got an A in high-level econometrics in college. This is not because I got good at math. This is because my mom taught me, through the school of hard knocks, a secret weapon: sitting on my ass and studying, until I understood a concept.

My upbringing was only 75% as strict as Ms. Chua’s daughters’ (no 7-year-old deserves to be yelled at for a whole day for not playing a piano piece,) but nevertheless, it fell into the framework of familial guilt and discipline that is so lacking in Western methods and that she outlines in her piece. When I was younger and my mom told me that my academic or personal performance had caused me to, “vimatat vse nervi,” or literally suck and unwound all the nerves out of her, I was afraid that she was going to die because I was causing her so much mental damage.

I hated the system (no TV during school nights; chores without an “allowance”-what the hell is an allowance, my dad asked. You should be grateful we let you live here without charging you; harsh punishments when grades were below the expected; and, the occasional slap when I got out of line or mouthed off.) I was terrified of my mother when I got bad grades and when I did something even slightly suspect. At some points I wanted to die or at least run away to my friend’s house, where movies and fast food treats were abundant and they didn’t have to do homework.

Looking back on that period now, I couldn’t be more grateful, and I hope I have the guts to raise my kids the same way. I don’t see any lasting “psychological” damage to myself as an adult: I love both of my parents very deeply and I love to spend time with them. I am moderately successful, have a career path, outside hobbies, and am self-reliant if need be, which is all I think my parents were asking for when they raised me the way they did.

But more and more lately, I’ve been wondering, how can Mr. B and I raise our nonchildren to successful? What was it about the way that my parents raised me that made me relatively successful and others not? How much of it was my own doing and how much of it was them? What if we fall prey to American parenting philosophies?

I’ve come to the conclusion from the WSJ article that I don’t want to be as harsh as Chua was. Making a child play a piece until she breaks down will hopefully not be my modus operandi. And kids should have sleepovers from time to time-I still remember some with very fond memories.

But I would not like my kids to be “soft,” at least the way I understand it. I don’t want them majoring in philosophy or Art History, at least on my dime, because there’s no way they’ll get a job. I know. I wanted to major in English (HA.) Luckily I was steered away because my mother wisely saw that my third choice of economics would be a much better investment. And now I can write, in my free time, on my blog (and make no money.)

I don’t want them to think that “trying their best” is trying hard enough if they’re not getting As. I don’t want them to think that, just because they’re “bad at math, ” like I am, that they have an excuse to slack. I want them to understand that learning problems can be mostly solved by a good hour or three of sitting on your ass-ness and studying. I want them to understand that getting an allowance is bullshit and that everyone contributes to the household equally. I want them to learn that quitting is bad for you and that you should always do things that make you proud of yourself. I want to teach them that sometimes doing things inside the system will make them suckers. I want to teach them that respecting your parents is important, and that your parents will be there for you forever, not just until you finish high school and they start redecorating your bedroom. And the way to do that is the only way I know how, the way I was brought up. Are there other ways that will yield the same result? Possibly. But I don’t know them and I’m not interested in pursuing them. I just know that my parents parented me correctly for the most part (like someone said, no one survives childhood unscathed) and gave me a huge gift in understanding how to navigate life so that I can do it myself and without their help as I get older.

Most importantly, I want to give my imaginary children the greatest gift that my parents gave me: the ability to see and understand both the Western and the Russian or immigrant system intimately from the inside and make the (ahem. Russian) choice for their own children. Because if we have kids, they will be the first generation born in America, and they’re going to lose some of that third-culture kid perspective that is SO important to me in understanding and defining my world. And I’m going to fight to make sure that they don’t and don’t assimilate gently into that good night. And maybe, in between piano lessons and temper tantrums, that’s what Chua was fighting for the whole time?

Anyway, if you were raised by Western/”Eastern” parents, what are your thoughts? What do you see as the primary difference between American parents and immigrant parents? Which path is worth pursuing (this section sounds suspiciously like an essay test.)