Book Review: Salt: A World History

It’s been a while since a book review, hasn’t it?

I picked this up at my local library because I like histories of things, I like food, and I LOVE salt. So does Mark.

Salt is, as you might have guessed, about the history and importance of salt in human life and how it’s shaped our politics and cuisine over the past 2,000 years. It’s not quite linear, instead being broken up by civilizations and jumping back and forth throughout history.

The first half of the book is mainly about how humans and animals need salt to replenish nutrients in our bodies and how animals started finding salt in nature, which humans followed. The reason for this is that carnivorous animals don’t need salt in their diets, as they get it from meat (Kurlansky writes that Masai warriors supplement this need by drinking the blood of the animals they slaughter). Domesticated animals do need to supplement it, which is where the great search for salt began in human life.

Salt is also basically a miracle crystal:

As a result, until people learned that they could produce salt synthetically, huge battles were waged over it. Many towns and cities are built around salt formations, and salt paths that lead to salty water or salt licks (a term you shouldn’t Google Image Search). Once people realized that you could form salt by evaporating sea water or mining it, whole industries and civilizations formed around it. Kurlansky starts by describing how salt in China led to the discovery of gunpowder and the creation of elaborate bamboo pipe systems that laid the ground for the first public utilities.

Later, he talks about how Egyptians salted their mummies, how Phoenecians traded salt, which resulted in the spreading of the Phoenecian and Roman alphabet, about the saltworks in India and their role in India’s independence, how the American revolution and French revolution resulted from salt taxes, and lots of interesting tidbits and history. If you read this book, you get a world cultures refresher, as well as Trivial Pursuit winner for life.

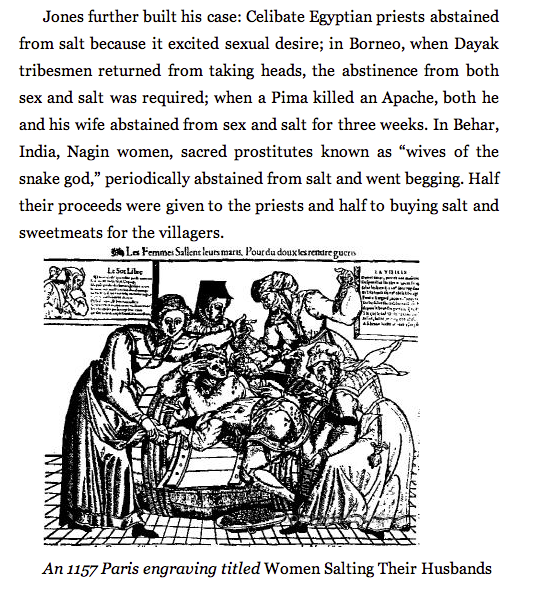

Kurlansky also has pictures of people salting other people:

Here’s a cool recipe you can try with your kids:

After reading this book, it’s amazing to me how much of our traditions come from salt. During a Russian wedding, you’re supposed to eat bread and salt, and bring bread and salt into a new home. In Judaism, you dip the challah in salt on Friday nights to symbolize your commitment to God (or whatever. Real Jews can fill in my information that I was too lazy to Google here.) We throw salt over our shoulder to bring good luck, and I put tons of salt on my scrambled eggs to make sure I have an awesome day. Kurlansky also outlines words that come from salt; for example, sal is salt in Latin, which made its way to soldier in French, because at one point soldiers were paid in salt. Salary comes from the same root, meaning “Worth his salt.” It’s even more obvious in Russian. The Russian word for salt is sol’, soldier is soldat. Not everyone likes word nerd tidbits, but they always blow my mind.

This book is so in-depth, and such an interesting read even though it tackles what could possibly be a tedious subject. If you’re looking for a beach read or something to read on a long vacation that will impress your nerd history friends after you’re done, this is it. It also has some cool recipes, one of which I actually tried with mahi-mahi (Sardinian fish, layered with tomatoes, onions, lemon, and salted thoroughly, doused in olive oil and left in the stove for about half an hour.)

There are a couple of minuses. The main problem with Salt is that reading it is a little like watching Anthony Bourdain mercilessly eat his way through Morocco or El Salvador before you’ve had dinner. You are constantly hungry. Because Kurlansky always talks about salting things like cod or pork, about including salt in bread production, even in wine production, you get the idea, and he includes recpies (from as far back as the 1500s) to indicate how important salt was in preservation. Also, I skipped over some parts of the book that talk about salt production and chemical processes because they’re not as interesting. At times, the book plods on (after all, it is almost 500 pages.) But in general, a great read.