Refusenik

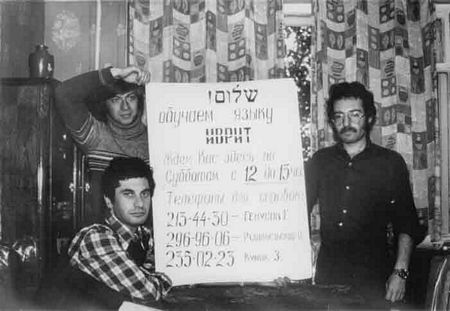

A couple weeks ago, Mr. B and I watched Refusenik, which is about Russian Jews who did not spend hours blogging about why Russians love Ferrero Rocher and misunderstanding song lyrics, but instead stood up to the full might of the Soviet government at the height of its power and tried to leave the country.

It’s insanely difficult to imagine the strength these people must have had inside themselves to do this, knowning full well they might go to jail. By the 1980s, everyone in the Soviet Union understood what the gulag might be like, for years on end.

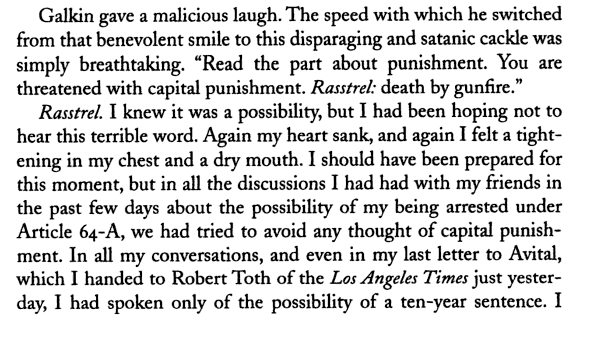

Natan Sharansky, who I’ve been lucky enough to meet in person, was one of these refuseniks. He spent nine years. NINE YEARS. in confinement.

It occurred to me just how cruel unjustified imprisonment is, not because of the starvation or the dysentery, but because they take away what you can never get back, those precious years of your only precious life.

After the movie was over, Mr. B and I wondered, as we usually do, if we could have done the same; spoken out against the government even if we held comfortable jobs or were prestigious national scientists.

After all my grandpa did it in 1980, when he applied to leave for Israel with his family. The Soviet government, of course, rejected his application, made him, my grandmother, my mom, and my aunt leave their jobs, and asked him to come to a Party meeting denouncing Israel as a disgusting and unproletarian place to live. While this was extremely beneficial to me because had my mom left for Israel when she was 18 I’d never have been born, it was not such a pleasant experience for them.

The answer we came to was, “No.” There’s no way I would have given up a cushy government job and a steady paycheck to speak out about something, even if I was absolutely sure that it was true. Even if it was my identity.

And I think that made me more scared and disgusted than anything in the movie. That I could allow myself to live a lie for the sake of a safe harbor.