Don’t Share This

I’ve been thinking a lot about privacy.

You always read those stories about how we don’t have privacy anymore in the media because of data, and how Zuck said privacy doesn’t exist anymore, and how now you can put people into privacy holes in the Gooch (this essay, which I constantly link to, is still one of my all-time favorites about the tech industry.) If you have your name linked to your entire online identity like I do, you think about it extra-hard because there’s no advice on how to be private after you become public.

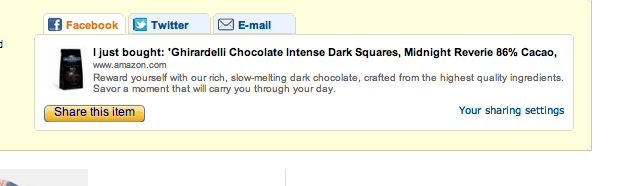

But something has specifically triggered alarm bells for me. For some time now, Amazon has been letting you advertise what you’ve purchased, immediately after you’ve purchased it. Here’s one from something I bought last night:

The first time I saw this feature come up, I was scared out of my mind. I think was buying this. Who wants the whole world to know that you’re buying a scale? Or one of the numerous other private things you can buy from Amazon? Underwear? Weight loss pills? Cream for when you have a pimple breakout? Food in bulk?

Buying these things in and of themselves is not embarrassing. Amazon is benignly watching you via its recommendations engine and sifting through the data it collects on every page you visit. That’s fine, and anyone who knows anything about how data tracking works understands that your existence on the Internet starts with Google, Facebook, and Amazon, and only goes from there. You can browse anonymously, but there’s no point anymore.

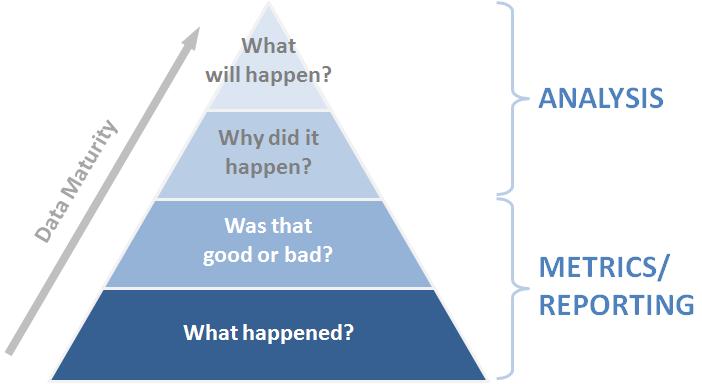

Some of the ways this data is analyzed is efficient and scarily accurate. As most data scientists (me!) know, though, data is messy and inefficient, and unless you really know what you’re doing, it can be an immense struggle to create linkages and make a model of a person from raw numbers that you get. For example, that story about how Target figured out a girl was pregnant before her father did probably took years of analytics, and they couldn’t do it at all before they had Target.com. As a data analyst almost anywhere, you will spend 80% of your time establishing the data and standardizing it, and only 20% of your time really digging into figuring out what will happen.

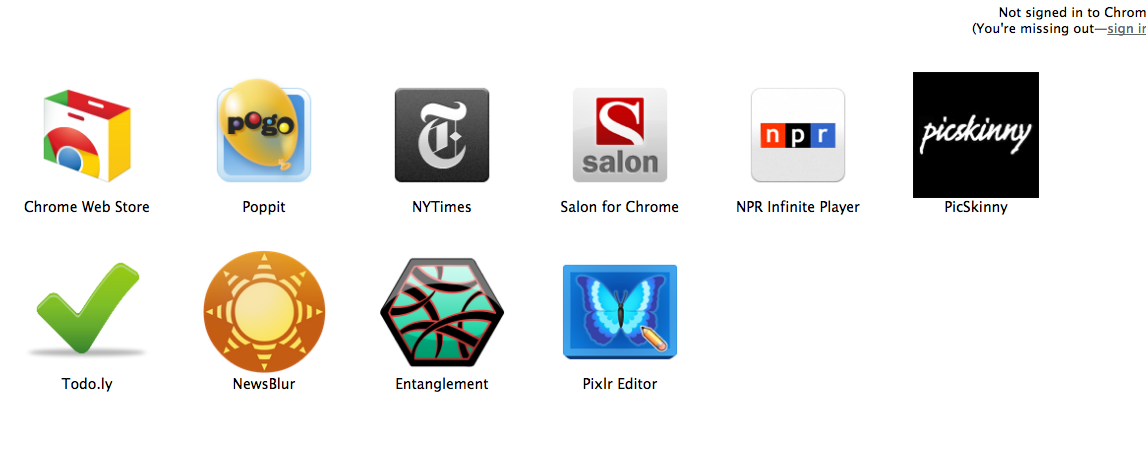

The really scary part is when companies scale to the peak of the pyramid and hit the golden 20%. They then change your understanding of what they know about you and how that knowledge can get to other people. I freaked out when Amazon offered me the option to share my purchases, and when Google Chrome offered me the option to sign in, I knew immediately that they wanted to link my browsing history everywhere and had the capability, which I didn’t realize they had before:

I was also made extremely uncomfortable when Quora, a company I was beginning to really like, changed its settings recently to allow anyone to see what questions you’ve viewed, and that to view anonymously you have to opt out or completely log out of Quora altogether. I then found out that Quora is made up of ex-Facebookers, and it began to make lots of sense.

Privacy, as I understand it today, then, is not sharing or withholding information, but the understanding that YOU have the power to share or withhold your own information before the settings change on you and everything you’ve viewed is exposed. That’s why I’m comfortable posting to my blog that I bought a HUGE amount of dark chocolate to crumble into my Greek yogurt, but I don’t want to tweet it through Amazon. As long as I’m on Vickiboykis.com, I have power over the information.

And then, I saw this quote on Hacker News, which really made me think:

Privacy is basically a historical accident belonging to the few hundred years in the west where transportation tech got ahead of information technology.

And I would say that’s essentially true, as well. My understanding of history right now is highly skewed towards the Russia of the 1930s, which was one of the worst times for human privacy in the history of mankind. Not only did everyone have to live in highly collectivized apartments, often sharing kitchens and bathrooms between groups of families (and yes, there was no sex in the Soviet Union,) but everyone was constantly suspect and many houses in Moscow were wiretapped. Many people were followed in Black Marias until they lost their mind. In the Czechoslovakia post-Soviet crackdown of the 70s and 80s, ordinary citizens were constantly targeted and photographed.

And yet, the only people who were genuinely unhappy about the Soviet Union were the minority of dissidents. Of course, we’ll never know how many people were really hurt by the lack of privacy, but having talked at length to various family members about it for research, I realized that the only people who were truly unhappy about life in the Soviet Union were those who knew something else, or who understood really that the Soviet Union was a police state. Not everyone did, and not everyone knew the capabilities of the government, and not everyone knew they were being photographed.

Which is to say, we live in a benign sort of data dictatorship today, hoping that it takes Amazon, Google, and the others, a long time to get to the really scary 10% of the pyramid. But maybe, inadvertently, we’re already there.