Our Father in Heaven, in the Kremlin

In December of 1812 when Napoleon was retreating from Moscow and the city was still smoldering from the great fire that Muscovites started to starve the French, Tsar Alexander I decided to build a cathedral as a thanks to God for saving the country from obliteration.

In the document he signed for the dedication of the church, he noted it was to be built

“to signify Our gratitude to Divine Providence for saving Russia from the doom that overshadowed Her.”

There were a number of problems with the construction of the cathedral. The first site was architecturally unstable. While a new location was picked out, a new czar, a conservative against the modern style of the original architectural plans, came to power, and everything had to be redrafted. A new spot was picked out, but unfortunately there was already a monastery there. The monastery was razed and by the time the construction was started, it was 1839.

That cathedral became known as the Cathedral of Christ the Savior and was completed only in 1860. After forty years of construction, the church was breathtaking. The inside was inlaid with granite, marble, and rubies. The outside domes glittered, gilded with electroplating. The church quickly became an important symbol of the state, as well as a gathering place for religious figures and a symbol of Moscow.

Less than a century later, Stalin decided that the new Soviet state did not have enough funds. He had been wanting to build a Palace of the Soviets on the site of Christ the Saviour for a long time (many of the other churches in Moscow and surrounding cities having been converted to potato storage facilities in light of the new policy of state atheism.) As a result of Stalin’s prodding, the economic department of the party investigated the situation in 1930, and found that the domes had at least 20 tons of gold “of excellent quality”, that

the cathedral represented an “unnecessary luxury for the Soviet Union, and the withdrawal of the gold would make a great contribution to the industrialization of the country.”

So in 1931, the Party first force-stripped anything of value from the church. Then they exploded it.

But because the Soviet Union ran out of money, then went into World War II, Stalin’s Palace of Soviets was never built. The empty spot served as a drainage ditch for some time, until Khruschev built the world’s largest outdoor swimming pool, the Moskva, in a country where the swimming weather lasts from early July to early August.

Once the Soviet Union fell in the early 1990s, a collection was taken up among the people to help restore the church to its former glory and donations poured in over 1993-4, despite the country being in the midst of a deep economic catastrophe. The cathedral stood once more.

In February of this year, Pussy Riot, a female Russian punk rock group that had previously conducted pop-up concerts in other public locations of Moscow, sang a song at the Cathedral. In it, they beseeched, in faux-Slavonic rhythm, for the Virgin Mary to drive Putin away from the country. After the video surfaced online, they were arrested and charged with hooliganism. Then, they were immediately jailed.

Their “trial” just wrapped up on Friday. In it, they were declared guilty and sentenced two years in Russian prison based on actions that would have gotten them community service or heavy fines in the United States.

But because it coincided with Putin’s “re-election” “campaign,” the government decided to target Pussy Riot and turn to the one thing the Russian government has always known how to do: rob people of their humanity, in this case, by putting the accused in a container known as “the aquarium”:

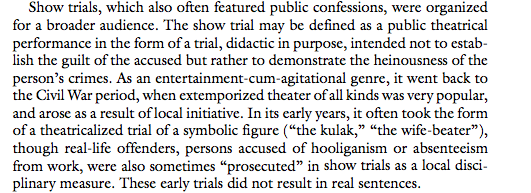

and conduct show trials that scare me in the way that, in order to conduct research for my novel I’ve only had to read the news from Moscow this weekend. Here is a screenshot from a book I’m reading right now about the 1930s:

These women have kept their humanity and read composed and thought-out statements given what they’ve been through over the past several weeks.

Were they right to do what they did? Would anyone want someone to come and desecrate a house of worship? No.

But, is it right to sentence three women, two with extremely small children, to two years in a Russian prison (which has a completely different meaning than an American jail) for what is essentially an Improv Everywhere performance?

Is it right to demean people, to remove every ounce of what it means to be human to make them feel small and insignificant against the crushing collective of the state? Is it acceptable to do this while the majority of Russian pop artists and directors and musicians stand by in silence because they are just glad it’s not them in the chair?

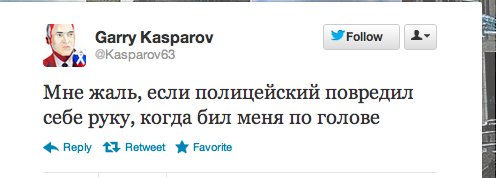

Is it also right to arrest national chess hero Garry Kasparov for the mere fact that he was speaking in front of the court house where the trial was occurring, and then to claim that he bit the very guard that hit him and shoved him into a police van?

At least he has still maintained his sense of humor so far:

“I’m sorry, if the policeman hurt his hand when he was beating me on the head.”

Is it right that the Orthodox church administration at Christ the Saviour proclaimed that Putin was a sign from God, and that the same administration probably collaborated in raising the stakes on their sentencing?

These questions are disgusting and unfathomable. But they are distinctly Russian, and have been asked over and over again for the past three hundred years, in different intonations, by different writers and thinkers. They read like something out of Master and Margarita, out of Crime and Punishment, out of the Bronze Horseman. We read these books and think, “How could such evil have existed in those times, and why didn’t anyone do anything about it,” and the answer is, because by making a stand, we subject ourselves to the full might of that evil, and through our silence, we allow it to spread.

The good news is that silently spreading evil is harder in the age of a 24-hour news cycle and Twitter, and we can combat ignorance and protest kleptocracy.

The bad news is that, no matter how much we think we know, history continues to cycle mercilessly and repeat in the same patterns as it has been for hundreds of years, and Russians seem particularly paralyzed in the constant ebb and flow of its currents.

In a way, the fate of Christ the Savior, and of Russian Orthdoxy, mirrors that of Russia – repeated hope on the verge of repeated destruction. Beautiful gold gilding, then explosions of epic proportions. Reinstatement, then collaboration with Putin’s government. Looting. Bureaucracy. The reduction of people to simple pawns that can be moved only by God and state, without any free will or predetermined self-destiny.

One of the largest ironies about Christ the Savior is that it was dedicated to the justice and mercy that God has shown the Russian people in the millennia that Orthodox Christianity has become Russia’s state religion.

But, once again, as has often been the case during Russia’s long and complicated relationship with its own vileness, God is, quite frankly, tired of Russia, and he’s out to lunch and a little short on mercy at the moment, else he would have heard the public prayer of the women in the cathedral in February, and, no doubt, the private prayers they have every night in their jail cells.