The edge of glory

According to some reports, 8 million-some people were simultaneously watching Felix Baumgartner with bated breath yesterday as he made his leap from the edge of the world. Although my heart pounded with nervous adrenaline for the better part of an hour, all I could think was, “What kind of moron would willingly sign themselves up for something like this?”

I’ve asked that a couple times over the past year. The last time I asked it is when Mr. B and I were at Mt. Rainier, listening to an experienced mountaineer explain what it takes to reach the peak, and how many people he’d seen lost to the mountain.

He talked about ice flowes, snow blindness, and equipment malfunctions. He described the long and torturous last leg of the ascent and descent where you have to camp overnight on a sheer ice cliff, eat an energy bar, and then make the last eight-hour push to get to the top and then start back down. All of this part has to be done in the same day, because it gets extremely cold at the top, and if the cold doesn’t get you, the winds do.

What kind of idiot willingly signs themselves up for hanging to live by the sheer strength of their knuckles, praying for the mercy of winds? What kind of idiot paraglides, or bunjee jumps, or skiis tripple diamonds in Chamonix, or lives life as David Blaine?

I don’t understand these people. Or, at least I thought I didn’t until watching the free fall, when Vysotsky came to mind.

Vladimir Vystosky, my favorite performing artist of all time, in addition to being a talented actor, singer, and songwriter, was also a mountaineer, and many of the songs he wrote reflected the spirit of the mountainclimbing and the allegories to teamwork and the hard work of scaling a peak. One of these is one of my favorites, called Skalolazka, or “Female Mountain Climber, “, which sounds really awkward in English because there’s no feminine word for mountain climber, (alpinista?), but in Russian sounds endearing and charming.

You can ignore most of the translation in the YouTube because it’s pretty bad (i.e. climberette), but it gives a good overall mental image. The text starts:

I asked you, why are you going up into the mountains?

But you were headed to the peak, you were chafing at the bit,

You know, you can see Elbrus just fine from an airplane?

But you shook in laughter, and you took me up with you.

The song goes on to talk about how a relationship with someone is like climbing tandem in a harness, how one person supports the other, and how she challenges him as a climbing partner, a lover, and a friend.

I remembered this song because every time I listen to it, I think of myself. I haven’t done anything extraordinarily crazy in my life. I would be too terrified to go skydiving or even stand on that glass platform thing they have over the Grand Canyon now. The highest I’ve been is on a horse. Oh, right, and the earthquake at work.

But every weekend when I’m doing homework or in class, every morning when I’m writing my novel on the train, every Tuesday night when I’m at the gym, and every Wednesday night when I’m at Weight Watchers, I ask myself why. Why do I do all of this to myself? I could be perfectly content sitting on the couch, planning out my week based on fall previews, living life the way I understand most middle-class Americans to be living life. I can see Elbrus just as well from an airplane as climb it.

The answer is that when I live that way, I feel bored. I feel like I’m cheating myself. There’s more to life than New Girl and potato chips. There’s more to life than endless commutes and living in the suburbs. There is proving that you’re human and alive and you can travel at the edge of whatever boundary you set for yourself.

I think we all have something like this, a nagging voice that tells us there is something we want to do that is weird and excessive to other people, but that we simply MUST do or we’ll burst. It doesn’t have to be mountain climbing. It might be quilting an entire quilt, or making pasta for millions of people to see, or quitting your job and starting a farm in New Zealand,or fostering capybaras or even, say, running the Jerusalem Marathon (ahem). But there is always something that is tantalizingly far away and nagging and out of reach until we actually do achieve it and prove ourselves. We can’t be whole otherwise.

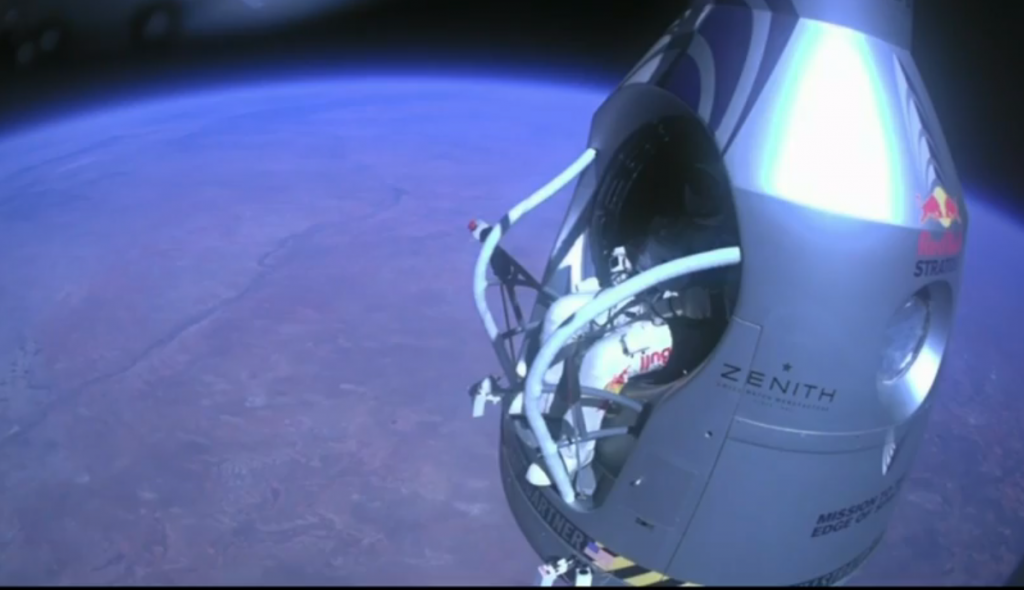

For Felix, that boundary was the stratosphere. I’ve read that there were hundreds of variables that could have gone wrong. First, there can only be a windspeed of two miles per hour or less to get the balloon, which is why they had to make three attempts. Each ballon is about as thin as your drycleaning cellophane, so they can’t be repackaged once inflated. Each one costs about $80,000 and has to be special-ordered. Yesterday, they were on their last balloon. If that one didn’t work, they’d have to back-order and wait three more weeks. This was a team of people who had all prepared five years for this day.

Then, once in the air, the first 4,000 feet were the dead zone. I.e. if he had to jump from there because of problems with the balloon, he wouldn’t have made it. Then, there was the visor fogging issue. Any one of the controls in the capsule. The air pressure.

On the way down, there was the issue of breaking the sound barrier. Losing all your internal organs. Going unconscious in freefall. Everything and anything, in milliseconds.

But then he was out of free fall and more than a tiny dot and floating and exhaling and then he was on the ground and there was the camera crew. Felix had done it. He had scratched his itch. He was, for the moment, satisfied.

What he did yesterday-probably moronic and completely useless on a scientific scale. But there is a reason 8 million of us tuned in yesterday: what it means to be alive instead of merely living.