I’m so happy for Ben Affleck

Why do we care about people we’ve never met?

Why do we cry over fictional characters that die? Why do we listen to gossip about our neighbors? And why do we skim the headlines of those magazines at the grocery store checkout line? What is it about human empathy that makes us this way?

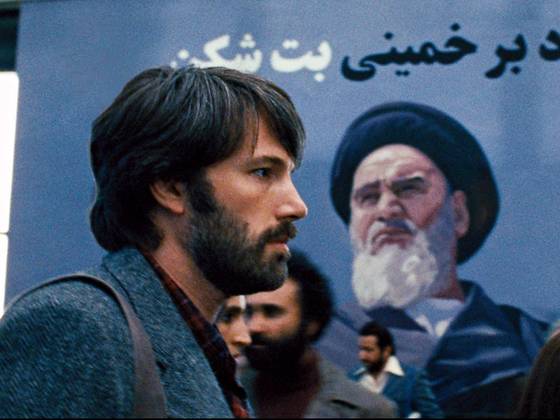

It’s something I’ve been trying to figure out after seeing Argo, Ben Affleck’s brilliant new movie about the Iranian hostage crisis of 1979.

The movie was so well-made and Affleck was so quietly brilliant in it that I wanted to cheer when it was over. I was so happy that Affleck’s career is back on track after the long national nightmare that was Gigli, and that he made a movie that felt like a solid BMW in a movie season that’s felt like flimsy toy cars.

It probably also helps that Mr. B and I saw Argo in a theater with a wine list.

The interesting thing is that as I was wondering why I was so happy for Ben, he was making me wonder the same question: why would people who had nothing to do with anything help and care about strangers?

The movie starts out with the storming of the American embassy in Teheran. We are there, inside with the consular staff and an angry mob waiting outside of the gates. You might not care about a few ambassadors and ther retinue in the newspapers, but when you’re put in their perspective, it immediately becomes terrifying. A mob doesn’t know people-reason, it’s its own organism, and you are American and you will die.

The first protesters break the gates and the deluge of angry people pour in, and the consular staff still doesn’t know quite what to do, but according to protocol they are in the back room, up to their knees, shredding documents like something out of Berlin in 1945.

Then the crowd is there, and they are escaping the building,and they are completely exposed Americans on the streets of Teheran.

They, according to the movie, flee to the Canadian ambassador’s house. Of course, real events transpired a little differently, but you gotta chop some stuff for the movie. Oh, and everything done-up in 1970s style, that decade I know so well in my subconscious: the outfits, the hair, the phones, the cigarettes. Everything is coming together like a good movie should.

All of a sudden, we’re in Washington, D.C., and we don’t care about the hostages anymore because we’re on another planet, one that’s much quieter and has stupid rules and protocols for how to deal with those pesky buggers overseas. But here Affleck is in charge and he pulls you along as he quietly plays Tony Mendez, the man who is going to save these people huddled in the middle of hell breaking loose.

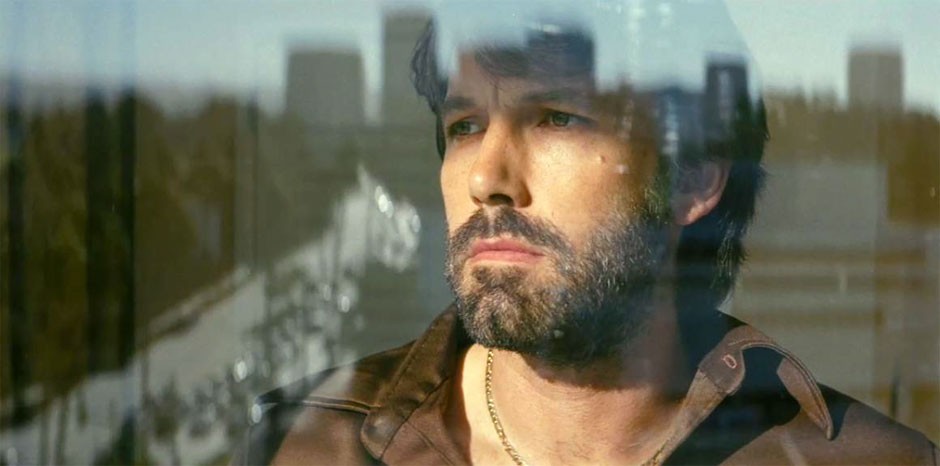

You are confident that Affleck will take you to a good place as the director, and you are confident that Mendez will get the hostages out because that’s his job, but also because he cares about humans. It’s obvious when one of his State Department counterparts suggests renting them all bicycles and having them pedal to the Iraq border as a first escape tactic. “200 miles on bicycles in the winter,” Mendez asks incredulously, in that one phrase making the whole United States government look ridiculous.

They just want to do something. He wants to do something well, because he knows there are real people on the line, and that’s the kind of person he is. He cares about real people, and he cares about doing his job well.

So he decides to go his own route and go under the pretense that he’s shooting a movie. Wired explains this well. After all, the movie is based on this article. He meets with two Hollywood people to get the thing going.

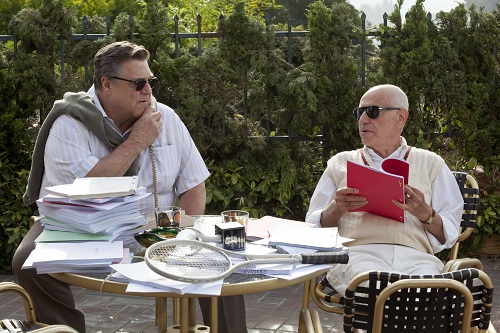

John Goodman and Alan Arkin are gems, just a pure pleasure to watch. They are veteran screen actors and they know exactly how to pull your strings.

They do all the Hollywood stuff. Mendez gets pushback from Washington. Then he doesn’t. Then the plan is off again. Then he fights for it. In the meantime, he’s trying to balance a separation from his wife.

In the meantime, these people are waiting at the Canadian ambassador’s house, helpless bait, their lives in the hands of others.

Then,finally, Mendez goes to Iran.

That nerve-shattering moment when his handler tells him he’s alone. He has no contacts. He either comes back or he dies. What makes people want to do these jobs? What made Mendez do everything he did in Iran to get the people out? Because you know he gets them out, but at what cost? That’s where the key of the movie lies.

How do people find the self-confidence they need in situations of extreme stress? When they are alone, and have no support? What made the Canadian ambassador and his wife hide six Americans, with no guarantee that they themselves wouldn’t be murdered?

What makes people tick, internally?

I’m still thinking about these questions.

Those mountains, those classic Iranian mountains, as the plane lifts off and your pressure is gone. They did it.

Don’t worry that I told you the ending. The movie isn’t about the ending. It’s about the process.

Can you look at the picture of the real Tony Mendez and understand what made him function the way he did? I can’t. People are amazing. They can do amazing things under pressure, surrounded by people who say NONNONO.

I’m guessing Ben Affleck was feeling some.

And he delivered.