Halloween in the city of good and evil

Three days before we were supposed to fly out to New Orleans, I heard that a “Frankenstorm” was supposed to end life as we knew it on the East Coast. Two days before, the owner of the AirBnB apartment we were staying at in the French Quarter called us to say that the ceiling had flooded from the upstairs toilet. He wasn’t sure the level of damage because he was in New York himself. Did we want to move to a hotel or risk it?

Our trip to the Big Easy came pretty damn hard, but then again, nothing is easy there. Lafcadio Hearn wrote about the city,

Times are not good here. The city is crumbling into ashes. It has been buried under taxes and frauds and maladministraions so that it has become a study for archaeologists…

but paused and concluded that,

..but it is better to live here in sackcloth and ashes than to own the whole state of Ohio.

He wrote this in the 1880s. People have been living in New Orleans much in the same manner since.

But we landed at Louis Armstrong International without incident. Except, “Did you notice that,” Mr. B said conspiratorially in the terminal. We walked past a sign welcoming Plastic Surgery, the Meeting, to New Orleans for the weekend, tacked up over two pieces of plywood.

“What,” I said.

“Did you notice that everyone on the plane was drinking?”

“Like, liquor? The tiny amounts that they give you for $10?”

“Yeah, liquor. There was even a guy with his own flask right by his Coke,” Mr. B made pouring motions.

There is something distinctly different about the Southern United States. People often make jokes about how neurotic, high-strung, and Jewish the Northeastern population is, but I’d never noticed it until we landed in New Orleans that weekend. From the get-go, there was a sense of benign neglect throughout the airport, almost like it was falling apart, but at the rate of one tile a year.

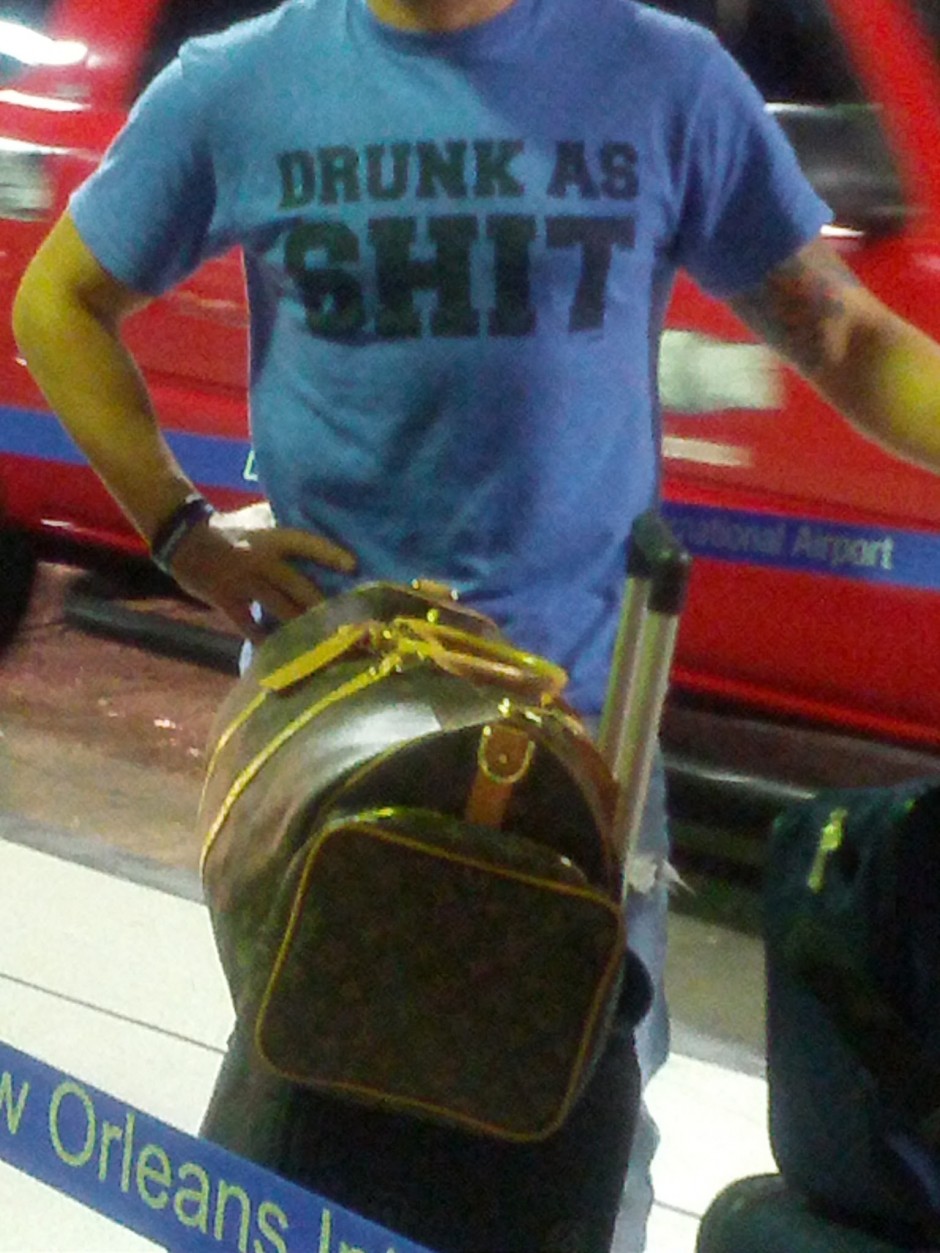

Listless passengers waited near walls stapled together with foam. Plastic clung to metal posts fluttered in the late October breeze. A man with a fake Louis Vuitton carry-on wore a shirt that screamed, “DRUNK AS SHIT” and waited patiently for a taxi.

“New Orleans is,” my hero Ignatius J. Reilly had mused, ” a comfortable metropolis which has a certain apathy and stagnation which I find inoffensive.” Time moved slowly here. The luggage belt moved slower.

Finally, we were in a cab and the palms in front of the terminal waved us a lazy goodbye as we passed. The road was dark and a full Halloween moon lit billboards for Mardi Gras float museums and alligator farms as Ella Fitzgerald played quietly on the radio. I began to get angry at the cab driver for creating shtick so we’d pay more, but I had begun to realize I didn’t care.

The French Quarter was still and paper ghosts fluttered above iron latticework and yawning shutters. Everything was tranquil, the calm before the Halloween storm, the calm before Sandy, the calm before winter. We’d decided to risk it with the AirBnB place. We walked through an iron gate into a cozy courtyard. The stairs were outside, like a Roman countryhouse. A tiny fountain trickled over ferns. A light was on in an apartment on the ground floor, where we could see an older man sitting in a rocking chair, sipping a bourbon he carefully poured from a glass decanter. Birds fluttered in multiple birdcages arranged neatly around his room. It was some grade-A Glass Menagerie-type shit.

The apartment itself was luckily fine, just a bit of water damage to an inch of the kitchen. The leak was much smaller than the owner had worried about, although the apartment itself did smell like hundreds of years of brine, like history. It had been impeccably renovated to include high ceilings, all-white leather furniture, and granite countertops, the unmistakable signs of yuppies. But, there was an enormous window that looked out onto the nearby rooftops and felt old. Its shape, the fact that it was imperfectly created to fit into the brick, at a time when large, airy windows were considered necessities, not luxuries, betrayed it. The fountain downstairs tinkled melodically.

We threw our bags down and headed out for dinner. The neat, darkened grids of the French Quarter were empty save a couple of women passing by in evening dress. Tall portable heaters flickered lazily near cafe chairs scattered outside. A brisk breeze was coming off the Gulf. We passed St. Louis Cathedral, silhouetted in spiky shadow. I took blurry obnoxious cell phone selfies.

The restaurant was an old carriage house with attached servants’ quarters and people sat outside at tables lit by tiny flickering candles while the steady clatter of silverware formed a comforting background din. The cocktails were fresh, the dinner was fresher. Time moved extremely slowly, in a way I’ve only experienced once before, on a rooftop in Israel.

I had no idea where I was, only that my friends knew of this hot music club and you had to go through a sketchy building and up three flights of stairs, onto the roof of a Bauhaus building in South Tel Aviv. Everyone was smoking hookah and the smoke wafted into my nostrils. Someone had played a guitar in the distance. I smelled the sticky-sweet nachla smoke and looked and looked at the stars.

I felt something essential in myself unwinding. There is nothing like sitting outside underneath a cypress tree in late October, eating fried crawfish. Nearby, a genteel woman wearing an expensive scarf leaned forward over her wine glass to talk to her date, a man in a blazer. At the next table over, two girls in costume were showing Instagram pictures to a guy wearing a bowtie.

That night, after walking up the quiet steps, past the iron gate, and the moonlight looking brightly into the the demilune window, we fell asleep to the noises of the fountain outside, trickling into the ages. Sandysandysandy, whispered my subconscious, but the fountain trickled on and on and I fell asleep.

***

New Orleans has had its struggles early on in the 18th century when it was claimed and reclaimed by the French and the Spanish, survived purchase by the United States, an influx of Hatitians in the early 1800s, and the Battle of New Orleans in 1812. The street signs are still in Spanish, sometimes.

By the mid-1850s, it was doing its thing, growing its own culture. It bypassed yellow fever epidemics, the Civil War, and numerous breaches of the levees, life that was essentially like living at the edge of an overflowing bowl. In order to compensate for a life lived constantly at the margin, New Orleans learned how to relax.

We relaxed everywhere in New Orleans.

We relaxed at Woldenberg Park, where we froze our asses off as we tried to run off the dinner from the night before. The park was named for a Jew who became prominent in the South for selling and distributing liquor to New Orleans, and then later for selling and distributing Judaism to New Orlenean Jews. It also, as is obligatory for every city in the United States, had a Holocaust memorial.

We relaxed here for breakfast. The line for Cafe du Monde was super-long, so we shrugged and skipped it. Why see a must-see destination?

For the first time of any of our vacations, we had no real itinerary. Nothing kills vacation like being a tourist on one.

We walked the riverfront. The Mississippi was at low tide, but still there in the distance, vaguely threatening. The wind was harsh and we bought, ironically, Scottish scarves.

Mark Twain had visited New Orleans a couple months after and a couple hundred years before us. He’d walked the same riverfront, seen the same river draining from hundreds of miles of the United States in the same river basin. He’d written,

It has been said that a Scotchman has not seen the world until he has seen Edinburgh; and I think that I may say that an American has not seen the United States until he has seen Mardi-Gras in New Orleans.

In theory, we weren’t that far off.

We ate slowly at Drago’s, a restaurant recommended by a coworker with ties to New Orleans. Drago’s is a New Orleans institution, founded by immigrants from Yugoslavia.

We relaxed at the Cathedral, where we peeked in the cracks in the large, weathered doors to see a Catholic wedding taking place.

We took whimsical selfies near the statue of a man who mass-murdered hundreds, if not thousands of people and almost beat someone to death by caning.

We took tours of the French Quarter and took pictures near colorful brick fronts cleaned up to their original glory.

We took the old, old trolley up St. Charles Avenue, where all the rich people live (we spotted three synagogues along the way,) to Tulane University, where we watched Indian exchange students play cricket on the lawn.

All of the houses on St. Charles were decorated to the hilt for Halloween.

We went to jazz restaurants where old Italian men played the accordion live while we drank cocktails. Music doesn’t sound as good ever as when it’s live. It flows through you. Or maybe that was the alcohol. But at some point, it doesn’t even matter anymore.

We people-watched on Bourbon Street over Halloween weekend in the dark. Some of those people were cross-dressed men. Some were undressed men. The street was crowded and full and it was as if everyone was in on some sort of secret that we all shared.

We watched Argo in classy movie theaters.

We prayed for things at Marie Laveau’s tomb, even though we didn’t touch it, because we weren’t sure what the cross in voodoo would have to do with the residue from the Wailing Wall. Don’t cross religious streams. We went to Voodoo museums.

And finally and most importantly, we visited Ignatius, who probably subconsciously inspired me to visit New Orleans when I read about him last year:

Ignatius had written,

The only excursion of my life outside of New Orleans took me through the vortex to the whirlpool of despair: Baton Rouge. . . . New Orleans is, on the other hand, a comfortable metropolis which has a certain apathy and stagnation which I find inoffensive.

As we made our narrow escape on the first of two standby flights into the path of Sandy, Pontchartrain gleamed quiet and blue and the ripples of sunlight winked a low, casual smile at us.

We agreed with Ignatius.