How to watch internet news

Ida Wyman, Newsboy with Checked Shirt, Los Angeles, 1950.

Twenty years ago, Neil Postman and Steve Powers wrote a book called How to Watch TV News that was assigned summer reading for my 11th grade economics/politics class. Ms. Beaver was one of the most important teachers I had, 50% of it stemming from the fact that she made us read this book and call bullshit on mainstream news.

The book was written at the dawn of the cable age, when there was no such thing as second-screen technology, DVR, Boxee, Netflix, YouTube, or news media to be consumed outside of print. But it still reads true. The second page says,

The fact of the matter is that television not only delivers programs to your home but, more important to the advertising community, it also delivers you to a sponsor. Advertisers and suppliers of programs spend a fortune slicing, dicing, chopping, and crunching numbers that will tell them what you are watching along with every bit of information about you they can get. They are not playing “Information Please.”

The kind of knowledge the advertisers seek give them power and the more they know about you, the easier it is to sell you something. Developers of interactive television boast that in the future they will be able to send specific commercials to their subscribers based on the household’s demographic composition.

That part is still off in the future, but it’s not as relevant anymore, because there is the internet. Cookies track every site we visit, and Google has, in a quiet, genius way, tied our identity to every one of their products. I am still holding out on the last bastion of privacy, Chrome, which you can sign into to synch across ALL of your devices, which means not only what you do in Google, but what you do everywhere is up for dissection. Fun.

Where am I going with this?

Right. The news is the news for a reason:

All this talk about news – what is it? We turn to this question because unless a television viewer has considered it, he or she is in danger of too easily accepting someone else’s definition-for example, a definition supplied by the news director of a television station; or, even worse, a definition imposed by important advertisers. The question, in any case, is not a simple one and it is even possible that many journalists and advertisers have not thought deeply about it.

Except that journalists think about it deeply today, when they try to phrase stories in a way that will boost clickthrough conversion rates that are so important to online advertisers. I do it all the time with blog post titles, except I don’t have advertisers, so it’s just to get people to click on content I think is interesting.

Which brings us to last week. On December 14, ostensibly the start of a slow news day before the holiday season, The Week posted an article called “The shocking number of deaths caused by falling TVs.” It was nothing more than a blurb, really, that mentioned a report which said,

41 people — mostly children — were killed by falling TVs in 2011

in bold letters. That same day, American military deaths in Afghanistan climbed past the 2,100 mark. Aside from those headlines, which were mere snippets at best, flickers in the deluge of global news, that Thursday was like most other Thursdays in America. 117 people died in traffic accidents. 71 people died as a result of gun-related deaths (suicide and homicide combined.) 13 people died as a result of food poisoning. The infant mortality rate was still an average of 6.8 deaths per 1,000 live births, 34th on the list of developed nations.

But I didn’t see any huge headlines, across multiple sources of media, loudly tracking every death of a TV falling on a child, or every food poisoning death, or of each one of the 71 people that were killed by weapons on Thursday, or multiple opinion pieces proclaiming we should have a national conversation about our policy in Afghanistan. Because none of those things would have generated the needed traffic, which is why they were all blurbs and buried 2-3 clicks into a site.

On Friday, everything changed.

A perfect news story, for journalists, is a Man Bites Dog story.

an unusual, infrequent event is more likely to be reported as news than an ordinary, everyday occurrence with similar consequences, such as a dog biting a person (“dog bites man”). An event is usually considered more newsworthy if there is something unusual about it; a commonplace event is less likely to be seen as newsworthy, even if the consequences of both events have objectively similar outcomes

And what could be more Man Bites Dog and than a school shooting? From the media’s perspective, there’s an element of suspense and surprise, just like in many Hollywood movies we’re used to, an element of injustice and tragedy, because the kids are so little that they were all innocent, an element of a plot twist, because the shooter was related to one of the teachers at the school, and an element of fear, because many adults in the United States are parents with children in public school systems. It could also provide emotionally-raw pictures of keyed-up kids crying, which, of course, get pageclicks.

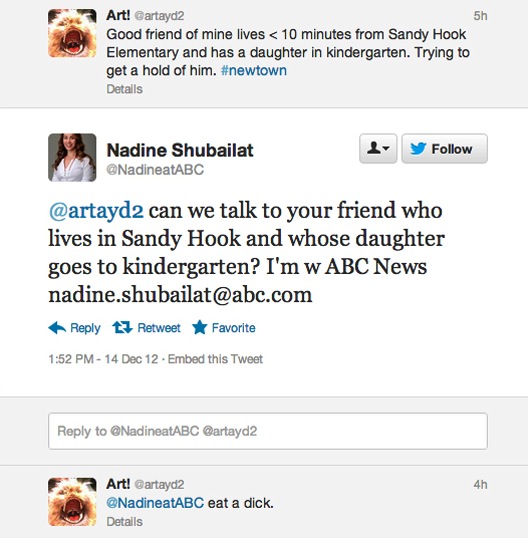

On Twitter, it was even more fun as news outlets decided to go for the full scoop and interview children,

and families of victims:

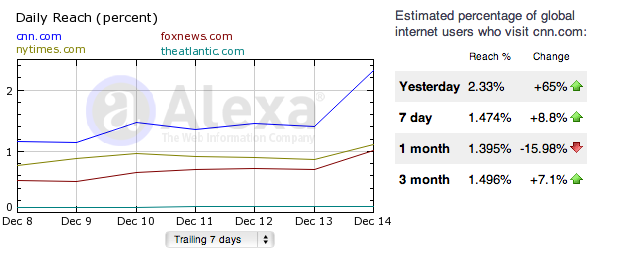

As a result, the news outlets had a field day. Traffic to CNN was up 65% day over day, during a weekend, when no one is reading news online.

Was it worth it, sensationalizing the death of people under the age of 10? Of featuring them in interviews? Of speculating and sensationalizing autism? Of making constant mistakes in reporting to get the actual story? Of instantly driving the debate in only one of two directions: mental health and gun policy?

For Buick, or whoever was the advertiser that day in the right-hand corner, oh God, oh God yes.

For our national psyche, absolutely not.

Why is the death of 20 children on one day more worthy of news than the children who died because the TV fell on them, or children that die slowly of malnutrition because food distribution in America doesn’t work, or children who die in childbirth?

Why are they being martyrized?

Roger Ebert gave a review about 10 years ago which has been going around lately, where he criticizes our media culture for glorifying murderers. He writes,

Let me tell you a story. The day after Columbine, I was interviewed for the Tom Brokaw news program. The reporter had been assigned a theory and was seeking sound bites to support it. “Wouldn’t you say,” she asked, “that killings like this are influenced by violent movies?” No, I said, I wouldn’t say that. “But what about ‘Basketball Diaries’?” she asked. “Doesn’t that have a scene of a boy walking into a school with a machine gun?” The obscure 1995 Leonardo Di Caprio movie did indeed have a brief fantasy scene of that nature, I said, but the movie failed at the box office (it grossed only $2.5 million), and it’s unlikely the Columbine killers saw it.

The reporter looked disappointed, so I offered her my theory. “Events like this,” I said, “if they are influenced by anything, are influenced by news programs like your own. When an unbalanced kid walks into a school and starts shooting, it becomes a major media event. Cable news drops ordinary programming and goes around the clock with it. The story is assigned a logo and a theme song; these two kids were packaged as the Trench Coat Mafia. The message is clear to other disturbed kids around the country: If I shoot up my school, I can be famous. The TV will talk about nothing else but me. Experts will try to figure out what I was thinking. The kids and teachers at school will see they shouldn’t have messed with me. I’ll go out in a blaze of glory.”

In short, I said, events like Columbine are influenced far less by violent movies than by CNN, the NBC Nightly News and all the other news media, who glorify the killers in the guise of “explaining” them. I commended the policy at the Sun-Times, where our editor said the paper would no longer feature school killings on Page 1. The reporter thanked me and turned off the camera. Of course the interview was never used. They found plenty of talking heads to condemn violent movies, and everybody was happy.

Poynter recently did a round-up of bullet points related to the shooting, a primer for journalists.

They note,

Schools are safe. After days like this, it can be hard to remember that schools are usually the safest place for a child. School violence has been in a steep decline since 1990.

Gun ownership is down but so is support for gun restrictions. The popular thought is that mass shootings will produce a movement toward stricter gun control. History indicates that is not true. Pew Research shows us that support for gun control changes very little after big incidents.

I couldn’t believe this when I read it, because that’s not what we’re constantly told. We’re consistently told to have a national conversation about gun regulation (so why didn’t we have one before?), consistently told that school shootings are extremely common in the United States, and consistently spoonfed statistics and data that will result in pageviews, not actual national dialogues.

We are taught to react immediately, without thinking. Without going through the slog.

“The television screen is smaller than life, “Postman writes.

It occupies about 15 percent of the viewer’s visual field….It is not set in a darkened theater closed off from the world but in the viewer’s ordinary living space. This means that visual changes must be more dramatic and extreme to be interesting on television. A narrowing of the eyes will not do. A car crash, an earthquake, a burning factory are much better.

Or a school full of terrified small children.

The Poynter article concludes with the comment that, “This story will take weeks to unfold.”

For advertising revenue, Sandy Hook already has.