Our own personal telescopes

Yesterday, Mr. B and I went to see Les Misérables with friends. I’ve seen the musical on Broadway and I’ve fallen asleep to Stars on a lot of nights in high school (I’m one of those people), so I was expecting a lot. Meanwhile, Mr. B, who hates musicals, braced himself morally and physically. Les Misérables, even as a movie, is three hours.

But the thing about making a movie out of a four-hour stage musical is —at the risk of sounding like a huge snob and a person you’d never want to have lunch with— that it’s the same as handing someone a square of Hershey’s chocolate and saying, “Oh, here. This is Nutella.” Because you have to cut out parts for the sake of the audience, you lose all the sticky goodness. You also have to use big-name screen actors who, except in the case of Hugh Jackman, and Samantha Barks (Eponine), are not stage actors, so you lose the ooey gooey filling that makes Les Mis, Les Mis.

“Film acting has no momentum,” crazy John Malkovich muses in this interview. “[going from film to stage is] like being a musician who grew up playing the piano, and here’s a saxophone,” and he’s right. The film medium is not the right one for Les Misérables because there is a vitality missing that’s present in the stage versions that only Sascha Baron Cohen and Helena Bonham Carter managed to capture an edge of. But only a sliver.

Plus, Jesus Christ, the close shots.

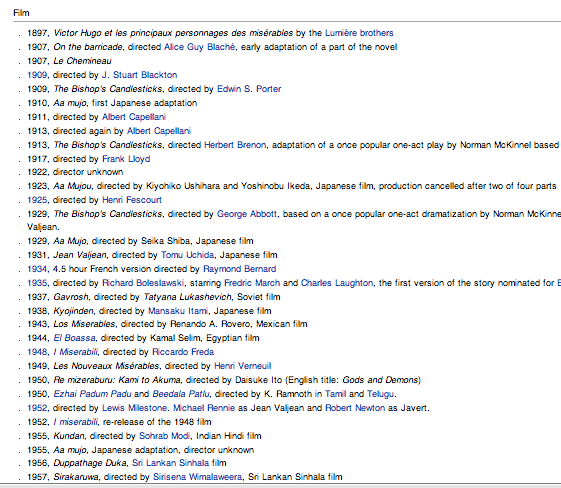

But the thing about great works of art, or any work of art, really, is that you are free to try and copy them as many times as possible, and the public will decide. I had no idea, but there are dozens of movie/screen adaptations of Les Misérables the book, from Sri Lanka, from Mexico, from Gavroche’s point of view, as vignettes. This is only about half of them:

There is really nothing new under the sun.

Here’s my theory about it. It has a lot of telescopes in it, because Mr. B bought one last year, so bear with me.

I like to think that all the world’s ideas are floating out there in the void (or in a series of tubes). Love, lust, betrayal, kings, identity, they’re all just tiny ideas, floating out there in the neural net of collective humanity. Writers or architects or painters or dancers or Jesus-Christ-the-close-angles director Tom Hooper reach out into that void.

Each person has a telescope that they use to see these ideas. The size of the lens of that telescope is the size of our life experience, the body we were born into, the country we were born into, the era we were born into. Using that telescope, we consciously and subconsciously pluck out the ones that matter to us most and give them our own twist.

The historical events Hugo depicted were not new. Desperation of the working classes as the the rich continue to be rich, redemption, love, and struggle, are all themes that have marked humanity since the beginning of time. Hugo just took a look through a 19th-century French telescope and wrote down what he saw.

Then, Boubil and Schonberg took their 20th century French telescopes and wrote the greatest musical of all time, based on that novel. Here’s my favorite rendition by my favorite Enjolras of my favorite song from Les Miserables, Red and Black (which is also a play on Stendhal’s novel of the same name):

Then, Tom Hooper took his really close-angle 21st century periscope and made the movie I somehow managed to sit through yesterday. Here’s Red and Black from that movie. Different, right?

That’s cool, Tom. I don’t mind your periscope.

But what I will say is that when Hugo was done writing the novel and waiting for reviews from his British publishers, he sent them a telegram. It said only, with baited breath, “?”

The British publishers replied back, “!”.

Tom Hooper, putting this out there, asked everyone, “?”

And I replied back, “(>_<)”.