Small data

The way we make decisions is really messy. But understanding why humans decide to do things is one of the great drivers of the current big data movement, so there are a bunch of algorithms trying to solve this puzzle for the benefit of $ociety.

One of these is decision trees. A decision tree is just what it sounds like, a group of paths of action you can take. Let’s say that you’re in the United States and want to take a long trip abroad. There’s a 50% chance you’ll go to Europe and a 50% chance you’ll go to Mexico. If you start in Europe, there’s a 60% chance you’ll go to North Africa next and a 40% chance you’ll go to Russia. The chance that you’ll start in the United States and wind up in Russia is a combination of the fact that you started in America first and went to Europe next, a multiplication of the two probabilities, 20%.

This decision tree we just made is called a training set. Data scientists take tons of these training sets and they run different sets over and over until the model knows the full set of options that a person has open to them. That’s how Amazon figures out what you might like to buy next based on other people’s purchases.

But just because someone’s likely path is Russia doesn’t mean they’ll go to Russia. Maybe they want to make a layover stop for Nutella in Italy and then they hear there are some great deals to go to Iceland, and maybe they can get to Canada from Iceland. Humans are impossible to predict and impulsive and don’t fit into training sets.

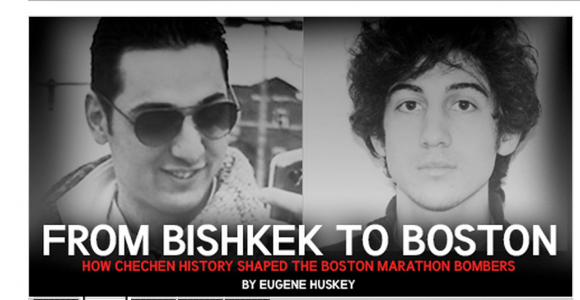

That’s why the media is going insane over the Tsarnaevs right now. Because the biggest question is, why would someone do something so awful? And the answer, based on the very few previous training sets the media has given us with since 2001 is that they are a Muslim extremist. If you are male, Muslim, Arab, and middle class, the odds are stacked against you. You’re already at 50%. If you are younger than 30, the odds go up. If you’ve ever attended a mosque, even higher. If you’ve done all that and spent time in Pakistan, you are 100% a terrorist.

But what if you have someone who committed an act of terrorism who doesn’t fit neatly into the decision trees and narratives the media has already pre-formed in our brain for terrorism in the United States?

It is the result of our story-teller nature. When facts don’t seem to go together, we collect more facts, just enough to form a narrative, even if the facts we can get are suspect.

You get the Tsarnaevs. They were ethnically Chechen, born in Kyrgysztan, and spent part of their lives there. But then they moved to Dagestan. What does that mean? What did they identify as? One of them has “Muslim” on his Vkontakte profile, but was he really Muslim, or just nominally Muslim, like most ex-Soviets?

Unless you understand Central Asia, these facts means nothing and have no context. You as a journalist might understand something, but your audience is American and they have even less context than you. (If you think I am being harsh on the American public, the Czech Republic actually had to come to America last week and say, hey, morons, we’re not Chechnya.)

Why did these men become murderers?

Maybe their decision to murder innocent people stemmed from a small incident in childhood when their mother told them offhandedly that they should always defend their Chechen identities and their father told them to defend themselves with fists if need be. Maybe this was a valid way to live in Kyrgyzstan, where ethnic minorities are still regularly manhandled. Maybe their father constantly suffered from looking for work because he wasn’t smart and didn’t know how to operate in the Kyrgyz system. Maybe he beat them as a result of the stress. Maybe they became extremely strongly Chechen as a result and viewed everyone else as outsiders.Maybe even when they moved to Dagestan, people made fun of their Russian accents, which weren’t Dagestani Russian accents.

Maybe, instead, they fit in perfectly but instead when they came to America they resented their parents for tearing them away from their friends.Maybe they had one interaction with an imam in Boston that started them down the path of Islam. Maybe they were born with mental health issues, something that’s brushed under the rug in ex-Soviet cultures.

Maybe none of this was true and they were raised in a bad family, inherently lazy, and were taught that humanity owed them something. Maybe living in a country that values women tripped them up. Maybe they were both demotivated slackers who didn’t want to go any further than a couple years of community college and, in their laziness decided national attention was the only way out.

It’s hard to say. Given enough time, we can get close to understanding the root cause. Humans are smart and can do decision trees better than computers, if they have enough context. But for now, our training models don’t fit this messy narrative.

Unfortunately, there is not enough time to go digging for context. People only read the headlines and maybe the lede paragraph of a newspaper item.

And, in the mad scramble to get eyeballs on the red area and put together facts faster than we can understand them, we get headlines like this:

and this:

With every additional neatly-packaged headline the media adds, it is fine-tuning our pre-existing training sets and doing the confirmation bias thing. We already have a list of people we need to watch out for: Arabs, Muslims, males, people wearing shoes, people in sunglasses and backpacks, immigrants, anyone from anywhere near Russia, and right, the Czechs, until we feel safe with nothing.

But the problem is that trying to figure out what happened is as much a small data problem as it is one of large probabilities and geopolitics of the Strong, Proud, Brave, Fiercely Independent Chechen People. It’s as easy and hard as going to the parents and asking, “Why did you raise your children to be horrible human beings?” and going to the remaining brother and asking, “How much of the responsibility of the fact that you are a monster are you willing to take on for yourself, how much do you attribute to the fact that you were probably constantly told how much better the Chechens were than every other people, and how much of it is due to the fact that maybe someone didn’t talk to you during a semester in college?”

But the human mind is so incredibly messy and takes so much time that by the point we have an answer, we’ve all already hugged our children and relatives, have instituted new safety checks in airports and at marathons, written editorials in newspapers, and have purchased our Never Forget memorial t-shirts.

But there are still hundreds of people whom are generating all the right signs in terms of small data, who remain unsolved, heading towards the end of their decision trees in a slow and frightening way.