The snarling crowd in the shadows watching us

By the time she died in 1886, Emily Dickinson had written over eighteen hundred poems. Only twelve were ever published in her lifetime, and they were published anonymously in the Springfield Republican, which, today, after significant infrastructure and population growth in the United States, has a circulation of 55,000.

So probably only 14,000 people received the newspaper that day when “The Sleeping” was published in 1862, and only a third of those, if that, ever read it. Five thousand people were only ever exposed to Emily Dickinson’s voice in her lifetime, and even that was anonymously and heavily edited to match publication style of that day.

When I was in seventh grade and memorizing tons of Emily Dickinson to make myself seem smarter to people older than me, I used to think this was incredibly unfair. How could someone so talented not want or need any exposure? How could she have died, unrecognized, unappreciated by anyone except her own family? She even asked her sister to burn all her manuscripts and correspondence, and it was only through a legal loophole that her legacy survived.

It used to be that there was nothing as unfair as a brilliant writer, toiling in obscurity. Now, it’s unfair that when we write, we face the universe.

That’s an exaggeration, but the recent explosion of viral content means that every time I write a blog post, I have to think about everyone that reads it: my family, my friends, my coworkers at the office, my coworkers at other offices, my dentist, people on Twitter, people on Facebook, people who repost my content in Japan or India or Korea with my blog name with my first and last name, out there in the internet.

This is obviously a choice. I chose to write, and I chose to write publicly, partly because of Penelope Trunk’s post . I could have hidden my last name, or even my first. When I first set up the blog, over five years ago, I toyed with the idea of blogging anonymously. I didn’t know much about security then, but I had a nagging feeling that, no matter how anonymous I was, I would always be found out.

What got me to thinking about how exposed we are in the modern world was this recent post experiment, where the author tries to start an anonymous blog. It outlines numerous steps he or she takes to be safe, up to parts that are extremely annoying to implement:

Most of the time I hide the stick in a secret location in the house. When I need to go somewhere and want to be able to update this blog, I’ll back it up to the hidden volume, and then securely erase the USB disk, so I can take it with me without fear. This is what I must do until the Tails adds its own function for ‘hidden volumes’.

But the author is already not anonymous in any way. They are clearly a native or near-native English speaker. They are tech-savvy, including knowing enough about both Tor and static-site generation using GitHub. And, they read XKCD comics. I’ve already created a pretty narrow profile of them in my head. They note that they counter identifying writing patterns by:

running all my posts through Google Translate. I translate into another language, then to English, and then correct the errors. It’s great for mixing up my vocabulary, but I wish it didn’t fuck up Markdown and HTML so much. Until this point, you might have assumed that English was my second language. But let me assure you, I will neither confirm nor deny it.

For the blog author, it’s an experiment. For most humans, it’s an impossible way to live. The danger of human nature is two-fold: the first is that we’re creatures of habit, which makes it easy to track our patterns, and second is that we are lazy. We’re not machines, and we’re not perfect.

The result is that now every time we post something, we’re posting it, non-anonymously, to a potential audience of over 20,000. 300 Facebook friends, each of which have 300 Facebook friends. Even when it’s only 100 that are possibly reading your posts, that’s a million people 2 degrees of separation away from you. Your private emails are no longer private. Assume someone’s reading over your shoulder, even your Angry Birds stats.

Once you are leading any kind of online life under what is even vaguely close to your real name, you have the potential to reach millions of people every day. And there’s no way to hide who you are, because that makes you even more visible. “The internet is no longer divided between a place between those who make, and those who consume,” writes Grace, and I agree with her, but for different reasons than she probably thinks. We are all creators now. We’re generating hundreds of millions of data points, sometimes unwittingly.

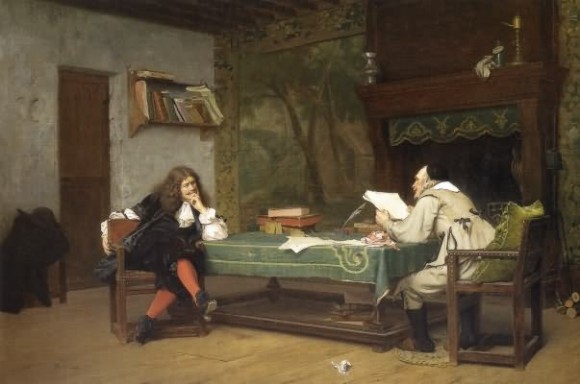

Every time I open up WordPress, I feel like I’m standing in a darkened club, front of an open mic in front of an enormous audience. There are a couple tables up front with friends and family, cheering (some are really loaded up on mojitos, so they’re being extra-loud). The rest of the audience is whispering among each other, not paying attention, flirting, filing their nails as I choose my words carefully. If I say the right thing, the people up front laugh and titter, and some people around them tap their shoulders, “Hey, who’s that up there. She seems interesting and funny,” and they tune in. Otherwise, they stop listening.

But if I say something that is absolutely true for me, that makes me feel vulnerable, or something funny that other people don’t think is funny, if there is even a breath of scandal, the entire audience snaps to attention and starts talking to directly to me or throwing tomatoes, and now there is a mob. Sometimes there’s a mob even when you don’t consciously evoke one.

I’ve deleted hundreds of drafts that I’ve started writing for exactly this reason. I’ve started drafts that are funny, sad, and angry, really, a number of drafts whose only commonality is that they are 100% what I believe or am going through, unfiltered by my fear of the snarling audience in the shadows.

Now they are, like Dickinson’s letters, gone.

If only we were fortunate to be able to delete other data before it makes its way through the crowd and the crowd buzzes in a murmur and rises to a roar, wanting to consume us.

It’s a really exhausting way to write, and, as Emily would probably say, a harder way to live.