On #sochiproblems as I see them

from “Let Me Stay Overnight“

from “Let Me Stay Overnight“

When I was eighteen, my dad finally took me back to Russia. I had been begging to go since I was nine because I had been having dreams in where my grandmother and my aunt spoke to me in Russian and reminded me that it was my obligation never to forget the Volga. These dreams were intense and immense, looming over my childhood and saturating it with guilt.

Immigrants always wear an aura of survivor guilt that they’ve abandoned their countries, and even though I was only five when I left, it was imprinted into me with everything my family did. I was taken away from what was the worst country on Earth so I could live in America. I survived, and because of that, I needed to feel guilty the rest of my life that others had not been so lucky.

When the plane touched down at Domodedovo, I was overwhelmed. “That’s your birthland,” my father said quietly through the window. Russian doesn’t have an exact word for homeland, only birthland, which means the country and the language keep you umbilically close, almost hostage, even if you leave.

All of the emotion I had been feeling my entire life, about my Russian roots, about Russia itself came together and apart inside of me and I felt like I could burst. I sat, looking at the runway and the grass on the sides of it. It seemed so much more Russian, somehow. Everything seemed more inexplicably Slavic: the sky, the buildings, and me. “You need to get off the plane,” the Aeroflot stewardess said icily, not looking at me as she passed by in spiked heels.

That first night, I lay in my aunt’s apartment in Yaroslavl. I had played here as a toddler for countless hours, and everything was as I remembered it, but much smaller. I had only remembered it in my dreams for the past fifteen years, and I had to keep touching the couch to remember it was real. The apartment, one bedroom where my grandmother slept with my aunt and one living room, seemed smaller. The kitchen was just a stove, a fridge, and a tiny table where my dad listened to Soviet news broadcasts as he ate breakfast over 20 years ago. Everything had shrunk.

But the crickets outside seemed much larger. There was no air conditioning, so the windows were open to the stillness of the summer night and the distinct Russian summer darkness came in like ink through a sieve. Downstairs, in the stairwell that smelled like piss and thirty years of crumbling damp concrete, someone clanged up the stairs, and my heart raced for a second until I remembered the thick black door with two bolts that had survived the lawless nineties. I’m back, I thought, this is Russia, with a sense of anticipation and fear. This is mine, mine, this is who I am, me, me, me, my mind echoed into the darkness of my dreams.

Two or three days after we came, my aunt, my dad and I took a walk, across from the cluster of Khruschevki project buildings where my aunt lived, to the place where my dad grew up in the 1960s, in a set of barracks. On the way, a wild pack of dogs ran by in the distance of the field we were crossing. “Stay away from them,” my aunt said, furrowing her brow. “They’ve been known to bite. We heard about it on the news.” The two-story barracks in their old neighborhood were made completely of thick strips of wet, rotting wood. “There was no real electricity or bathrooms when we were growing up,” my dad said, deep in his past.

“We were all so close. We had 2 meters of space per person, in a room for four people, but we knew all our neighbors. Everyone knew each other, all the kids were out here, always yelling, always playing with each other. Then we finally got that apartment, after years in line. ” There were still clothes hung out to dry on the lower floors of the building, and a deflated ball laying near the sidewalk. The barracks were still inhabited.

We walked further, past a school that looked like it should be in a bombed-out third-world country. The brick was sweating, the windows were pale and lifeless, unwashed from the 70s, and the playground was sad and dilapidated. I thought it was abandoned, but the bright pastel drawings and cutouts of leaves and stars in the windows told me otherwise. We walked past a closed-down disco called The Clockwork Orange. There were broken bottles and cigarettes everywhere. The building smelled of the same cinderblock piss odor as my aunt’s stairwell, like every stairwell in Russia.

For the first three days I was simply in deep shock. I grew up in America, and I had never been anywhere this dirty, this depressing, this-I didn’t even have a word for it in English. But there’s one that exists in Russian: toska, a combination of anguish, anxiety, and melancholy, and finally, acceptance that most things won’t ever change.

It shouldn’t be like this, I thought. It can’t be like this. How is it possible that the country that has produced the greatest literary cannon of the 19th century still has people using outhouses? We had beaten the French, the Germans, and sent the first man into space. (Later, I heard the wry Russian observation, “We beat Germany but they’re still living better than us. Maybe we should let them beat us this time.”)

I had a feeling I didn’t know how to reconcile. It was the feeling of simultaneously feeling proud of Russia, of loving Russia to pieces, but also one of complete helplessness. How to even begin fixing something like this, a country where people still live in barracks that weren’t meant to outlast Khruschev? A country where it’s reasonable to expect to to get bitten by rabies-carrying dogs?

And a third, uneasy feeling swept through me, and I recognized it right away: American smugness. Everything is so terrible here. It would never happen this way in America. How can people just take it? People would never be this okay with broken roads, heinous public toilets, and men staggering-drunk in the middle of the day where I was from.

And yet it seemed my aunt was proud of her city, of the fact that Yaroslav was part of the Golden Ring, the historic heart of original Russian Christendom. She was proud that The Scorpions, of Winds of Change fame, were rumored to come perform in Yaroslavl. How was this possible?

I had this feeling again when the hot water went off the second week we were there. Hot water always goes off in Russia for a month in the summer for “maintenance”. What, I thought as I my aunt calmly poured a cup of boiled tea water over my hair into the bathtub. How is this Russia, and how it it ok?

“I hate it here,” I told my dad after several days. “Yes,” my dad said. Despite having spent the first half of his life in Russia, it was beginning to weigh on him, as well. Russia weighs on you psychologically, like a heavy, wet blanket. “But don’t you dare say anything to your aunt. Mind your manners. Be good.”

“But why not,” I said. I was eighteen and stupid.

“You’ll hurt her feelings,” my dad looked at me, incredulous that I would even ask.

“Why can’t we talk about how we can fix the country?”

“Because you don’t understand anything about Russia. You’re an American. And if you say anything to your aunt I will be very angry with you.”

When we finally got back from that trip, and I entered America again, it felt like breaking through a tightly-sealed plastic container that was full of inky blackness at the bottom and ice cream and whipped cream and sprinkles at the top. I hadn’t realized how depressed I’d become in two weeks.

“How was Russia,” all my friends from high school asked eagerly.

“It was so gross,” I said, laughing. “Like they didn’t even have public bathrooms or hot water there, how gross is that?”

“Ewww,” they said, which was exactly the emotion I was hoping for. Shock at how bad things were, and admiration at me for bravely having gone through them.

But inside I was burning up with embarrassment for criticizing something I didn’t understand.

***

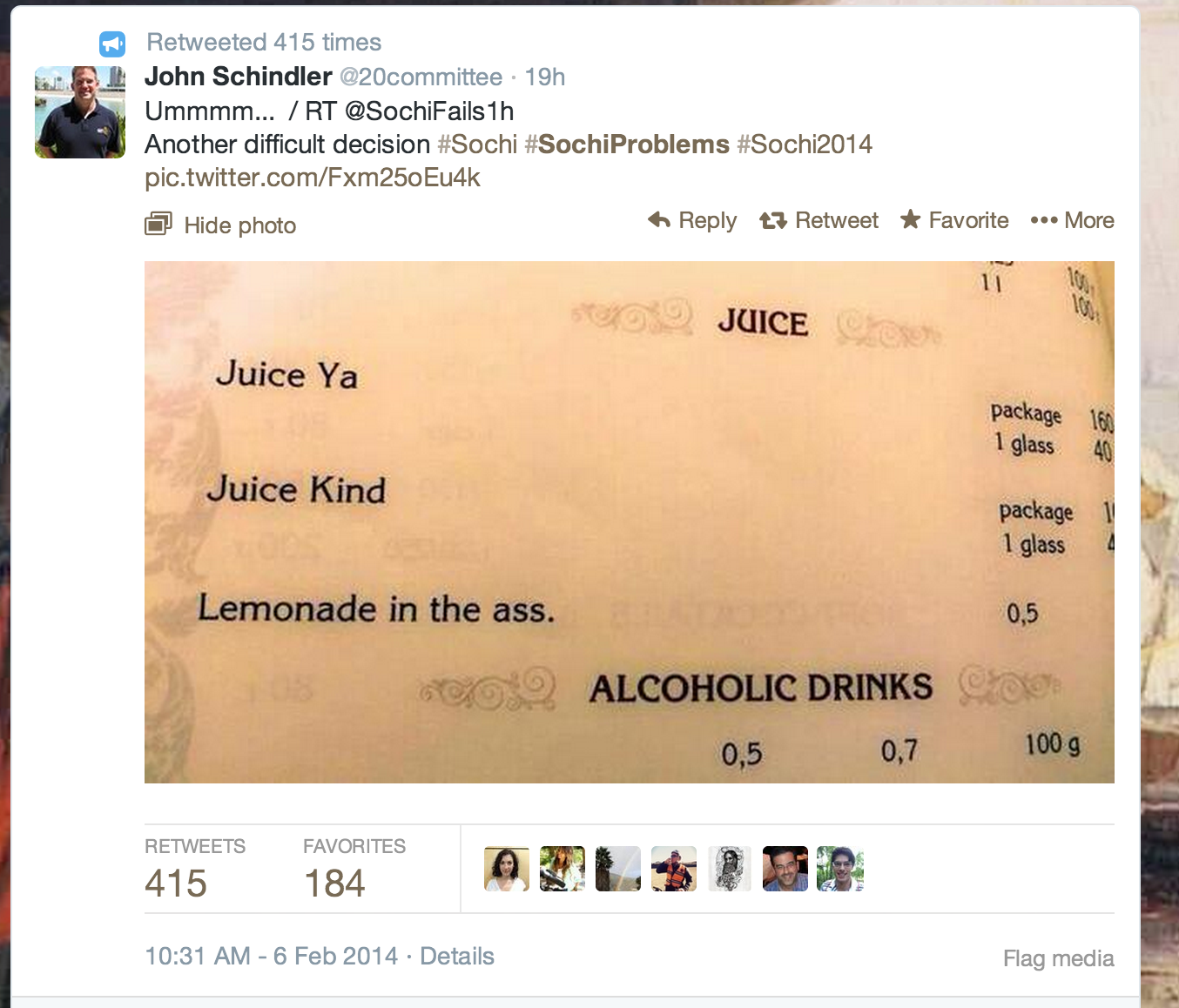

This duplicity of emotions is something the Western journalists teeming into Sochi and taking pictures of broken door handles and faucet water that looks like someone pissed out apple juice will never understand or be able to explain.

It’s not their fault, but they don’t understand that they’re missing the first two emotions: an overwhelming sense of love and obligation to the country, and a nuanced, detailed intuition about how things can be made better. Hence, when they process the unfinished hotel rooms and the unspeakable amount of public money that’s been stolen to build the world’s most expensive but worst-looking games, all they can come up with is, “Haha, this menu says ass on it.” (Ass. is the abbreviation for assortment in Russian.)

Added to this perfect storm is this feeling of exhibitionism, that they want to show the West how bad it really is in Sochi, without context, which is why they’re busy taking pictures of broken hotel rooms and writing sympathy pieces about how all of the stray dogs in Sochi are going to be rounded up and killed.

As opposed to…what? There are no shelters in Russia, and there is no system or culture of volunteerism due to the forced volunteerism everyone was made to do in the Soviet Union, so it’s a false dichotomy, a ploy from Americans, who are born pet-lovers, to hate those Evil Russians.

The more incredible and backwards-seeming the news from Russia, the more retweets journalists get, and there’s nothing journalists love more than being the center of attention. If they’re in it, it means they’re doing their job correctly. It’s, as Julia Yoffe said zlaradstvo, an evil glee, a kind of schadenfreude.

Within hours of arriving in Moscow yesterday, Russian friends, even the Westernized ones, those who are openly, viciously critical of the Kremlin, have expressed their hurt at the Western blooper coverage of Sochi. A whole lot of their tax money has been spent on something they may not have wanted and in ways they find criminally wasteful, and, yes, their government has not done much to endear itself to the West of late, but they’re puzzled by why the Americans and the British are so very happy that the details are a little screwy, the way they generally are in Russia.

The word they use is zloradstvo, literally: evil-reveling.

I’m more than thrilled that attention is finally being called to how fucked up Russia is; it’s only something I’ve been talking about for years. And it’s fine to make fun of something, but when that something is not your own, not something you understand, babies, goddamnit, you’ve got to be kind as Kurt Vonnegut would say. And kindness from journalists means adding context and not being sensationalist. Not playing the Ugly American Broadcaster.

And it’s very easy to be unkind in the face of unmitigated public attention.

Which is why the best people covering the Olympics are not any of the reporters that have been retweeted millions of times. Some of the best coverage so far has been by my perennial favorite, ViceTV, who first went to the sprawling Olympic complex, and then to the people displaced by its creation, who now live seven in a room and use an outhouse very much like the one nearly every family member I know did until at least the early 1960s. They also did a six-part piece on being gay in today’s Russia which I could only watch the first part of because of how cruel it is.

Unfortunately, in a mass public media event, being stupid and sensationalist is the only thing that will get you noticed, which is why the symbol of Sochi is now the toilet, instead of the people actually still going to the bathroom outside, instead of the hundreds of state officials paid to take bribes, instead of the underpaid laborers of the Olympic village, instead of the fact that the president of Russia owns a $200,000 watch while parts of Siberia have intermittent heating in the winter.

It’s hard to encapsulate context in a tweet,though, which is why this is the news we get.

Yes, there are Sochi Problems at Sochi, but they’re not the ones you see on the surface, and hopefully I did a good enough job explaining why.

Let the games begin.