The crapshoot of writing for money

I read recently that Karen Russell, who wrote one of my favorite short stories, St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves, won a MacArthur Genius Grant, which guarantees the recipient $625,000 over five years, interest and tax-free, to pursue whatever it is the author was doing that resulted in the Genius Grant award in the first place. That’s $125k a year.

Once you subtract out health insurance, gas, rent, Nutella, and other miscellany, that’s a very nice $90k a year to write for eight hours a day. The MacArthur Foundation is paying Karen Russell $40 an hour to do nothing but work on her craft.

When I read articles like this at 6:23 am on Monday mornings, squinting into the artificial light of my phone as I force myself into consciousness, I get jealous. Because no one is paying me so I can stay at home and work on my book for eight hours a day.

I’ve had people suggest that I could quit my job to write, but that’s terrifying, and to me, not an efficient use of my time. Why would I give up my well-earned income for the sheer terror of falling of a cliff and seeing if I land with a writing career?

I started writing this post before Emily Gould wrote about being a writer and how much it cost her, and now that I’ve read it, I am even more grateful that, even though writing is everything to me, it’s not how I make money.

Emily writes that she tried to stay a writer by choice,

Besides a couple of freelance writing assignments, my only source of income for more than a year had come from teaching yoga, for which I got paid $40 a class. In 2011 I made $7,000.

I read somewhere that the average writer makes $1,000 a year. Today’s Billfold post only confirms it:

January 2014 stats:

Total earnings: $3,300.91

Completed pieces (all types): 150

Essays published: 3

Novellas rejected: 1

Everyone is suddenly talking about how choosing writing as a career will lead to poverty.

Thomson is not yet broke, but he’s up against it. The story of his garret is a parable of literary life in Britain today. Ever since the credit crunch of 2008 writers have been tightening belts, cutting back and, in extreme cases, staring into an abyss of penury.

“Last year,” said novelist [Paul Bailey, speaking to the Observer in 2010](http://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/mar/07/google-writers-ebooks-publishing “”), “was sheer hell”. Off the record, other writers will freely confide their fears for the future, wondering aloud about how they will make ends meet. Hanif Kureishi, for instance, recently swindled out of his life savings, told me how difficult his life had become.

I sympathize for the writers who are struggling to make ends meet. The panic and fear of not having enough for retirement, not knowing whether you’ll have enough in the bank for the next month, is palpable and real, and numbing.

But the fact that only superstars get paid a comfortable salary is completely understandable. Writing books is not accounting. It provides no tangible value, and you can’t do the work reliably on a day-to-day basis. You can’t just sit down and pound out a novel like you would a budget. You can’t know whether what you write will be good, and most importantly, money-wise, if people will like it.

The only people who value literature, who would die for it, are writers and hardcore readers, and there are not enough of either in the free market. Follow the money instead of the writing, and find that, for the general public, there is no value in content at sites that are not writing-centric, and the market is flooded with people trying to make their dreams come true,

Nobody respects writers, yet everybody wants to be one (probably because everybody wants to be one). Point is, you want to be a writer? Good for you. So does that guy. And that girl. And him. And her. And that old dude. And that young broad. And your neighbor. And your mailman. And that chihuahua. And that copy machine. Ahead of you is an ocean of wannabe ink-slaves and word-earners. I don’t say this to daunt you. Or to be dismissive. But you have to differentiate yourself and the way you do that is by doing rather than be pretending. You will climb higher than them on a ladder built from your wordsmithy.

which is why freelancers make, sometimes, less than 50 cents a word.

Writing is an art. Writing for pay is a crapshoot. And any writer worth their salt knows it.

You have days of caffeine-fueled highs, where every word is a jewel, and you have days where you can’t write worth shit and you’re fat and other writers with book deals are drinking cafe in Paris wearing Burberry and you’re at home in your sweatshirt with a hole in the armpit, staring comatose out the window, because your mind-palace feels empty.

At the end of three weeks of crying jags, you might have a piece ready. You might not. You might have moved in your chapter. The chapter might be in the trashcan. You might have purchased a typewriter out of desperation. Every writer, even the very best ones, go through this. The unfairness of the world is that it likes results. People who deal in might-nots don’t get paid for their effort.

Writers are insecure and vain and crazy when left to their own devices, without the real world to be tethered to which is why I would never let writer-me provide for myself. Writer-me made $335.26 last year.

It’s clear, that if you’re not a wunderkind writer who has already been published by the time you are ten, and you don’t like poverty, you should not rely on writing to make you a living.

The whole writing industry, both literary and journalistic, is shifting. There are hundreds of thousands of writers in the market. No one is paying. What can we, as writers do? We can wring our hands and make it paycheck to paycheck, proclaim that it is the lot of the writer to suffer, wait for the money to dwindle away.

Or we can quit spinning the roulette wheel of fate. We can refuse to play the crapshoot, and button up, and just get a real job.

So I pay myself to write. I put in the time at work, long hours of thinking and connecting the dots, when I could be -am obligated to be, according to writers who refuse to sully themselves with work- at home, in my hole-y sweatshirt, cup of tea in hand, staring out the window, wondering why my character decided to board a train bound for Siberia. I put in my time at my MBA so I can continue to do the same thing for years to come.

It is true that I love what I do. I was lucky enough to get into tech when it was booming. But eight hours a day of concentrating hard on work means all your creative juices fly out the window by 6 PM and you just want to watch a TV show, man. And there’s another day of your life wasted because you have no completed novel. And then there are hours and hours of homework, writing term papers when you could be making flesh and blood people out of words on paper.

If you are a writer with a day job, it’s true that the job pays you, but you pay the job with your time and your attention, and, for waiters and baristas, with your physical energy, and this is what Writers with a capital W don’t like doing.

Virigina Woolf said a woman needs a place of her own to work without distractions, which include money. But not every person has a rich, mysterious (and handsome, of course) benefactor waiting to swoop in. So, I work so I can pay myself to be undistracted with bills at 6 a.m. on a Wednesday before work, or at 7 PM on a train headed to New York. I get paid, and I pay in return with my time. I have to be my own MacArthur Foundation, because the alternative is just too bleak.

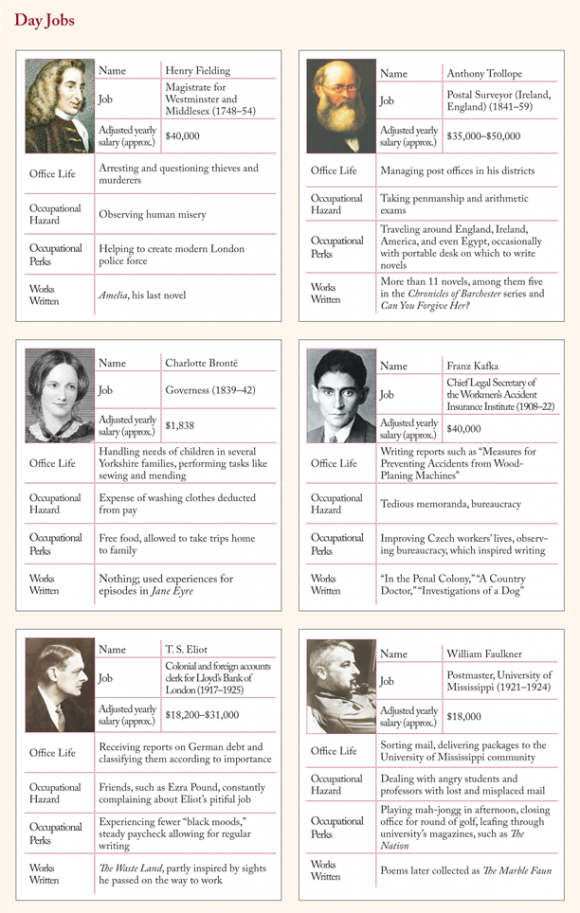

I am not alone. Anthony Trollope wrote two hours every day for twenty years before going to his job at the post office. Kurt Vonnegut worked at IBM. Faulkner, a postmaster.

What about women, with children? Tina Fey, cranking out Bossypants while she was in the middle of a career and child-wrangling.

JK Rowling says,

Whenever Jessica fell asleep in her pushchair I would dash to the nearest cafe and write like mad. I wrote nearly every evening. Then I had to type the whole thing out myself. Sometimes I actually hated the book, even while I loved it.

Lev Grossman, one of my favorite writers, has one of the most successful sci-fi/fantasy novels of the past ten years, and he still holds down a day job at Time Magazine. He writes,

[…]In the mornings I work from home for an hour or two before I go into the office. Not because there’s any particular reason for me to do that, except that by the time I hit the subway rush hour is over, which means I can probably get a seat, and if I get a seat I can crack open my MacBook Air and steal 20-25 minutes of writing time.

I’m always on the lookout for little gaps like that in my schedule: anytime I can get a block of 10 minutes or more, I take it. I write in waiting rooms. I write in cars while other people are driving (this is very boring for them, but I do it anyway). I write while pasta is boiling.

Sometimes when I’m taking care of my kids they fall asleep, or lose consciousness for other reasons. The second they do I’m at my keyboard. Ninja writer strikes! Then I go back to changing diapers.

Writing, the holy of holies, need not be separate from the secular art of making a day-to-day living for yourself. Both can go hand in hand, until you’re good enough for the MacArthur Genius Grant, or even start getting published regularly, I think.

I, personally, am not there yet. I might not ever be. It’s slow going, for sure. The 6:23 wakeup call gets me every time. And some days, I don’t write anything at all because I am just exhausted and wrung out, and can’t concentrate enough to jot down a single word as I’m drooling, scrolling mindlessly through Facebook.

But, nothing is guaranteed. Everyone prioritizes their worries. My way isn’t better than anyone else’s. My worries are making my mortgage payment and health insurance. I will pay to make those go away so that my real, nagging, deep-dark worry is that I won’t write what I want to before I die.

But I’m fine with this compromise, even though the novel nags at me every day, begging me to come back. “There’s no money in poetry, but there’s no poetry in money, either,” Robert Graves, the British poet, said, but he and his wife also got divorced because the stress of not having enough money was wearing them thin.

Which way to go? What to do? Everything’s a crapshoot, really. If you’re a writer, you’ll intrinsically lose something either way. Life is all about tradeoffs. Whatever you decide to choose, when you choose it, stick to it, with grit and panache. Sometimes, real life is the hardest thing about writing fiction.

Thanks to Ivan for reading this draft.