The American dream as seen through Polly Pocket

I am six years old again and I’ve been in America for a year. My cousin has been in America for six months, and somehow by the benevolence of our relatives, someone gifts her a Jasmine Barbie. I see it in her room, where she is staying with our relatives who sponsored our trip to America.

I am six years old again and I’ve been in America for a year. My cousin has been in America for six months, and somehow by the benevolence of our relatives, someone gifts her a Jasmine Barbie. I see it in her room, where she is staying with our relatives who sponsored our trip to America.

“What’s that,” I ask, eyes wide. Soviet dolls were all huge, ugly, and vaguely mechanical in nature, like if you tipped one over, springs and sawdust would fall out, like they were manufactured at the Petrovodsk Rubber Tire Plant Number 3.

All of my dolls were named Nastya, short for Anastasia. All of them had stick-thin stringy yellow hair, like mine.

This doll was tiny and shapely,and she had huge almond eyes. She looked like my cousin. You could never name someone that looked like this Nastya.  “That’s Jasmine,” my cousin, who is six years older than me, says matter-of-factly.

“That’s Jasmine,” my cousin, who is six years older than me, says matter-of-factly.

My cousin is the sun to my moon. She is pretty, popular, and has beautiful black-brown straight hair and eyelashes that reach her cheeks. When she tilts her head sideways and laughs, the whole world smiles. She walks, dreamily, paints with watercolors I’m not allowed to touch, wears clothes I’m not allowed to wear, goes places I’m not allowed to go. I am short, little, and have an imagination that the real world can’t hold. I wear hand-me-down clothes that look weird. I’m annoying. The only way I can get anyone’s attention is by doing funny things, or saying funny things. It’s hard to think of funny things to say all the time, so I give up and read books.

“Can I play with her,” I ask, reaching up . She is encapsulated in the box she came in. Most Americans throw these boxes away, but my cousin has kept it, meticulously attaching each piece of clothing to its original twist-tie, organizing all the accessories in one place. “No,” she yanks Jasmine away.

“Can I play with her,” I ask, reaching up . She is encapsulated in the box she came in. Most Americans throw these boxes away, but my cousin has kept it, meticulously attaching each piece of clothing to its original twist-tie, organizing all the accessories in one place. “No,” she yanks Jasmine away.

“You’ll lose her earrings.” “I promise I won’t. I’ll stay right here.” She hesitates, then carefully unties Jasmine from her plastic exile and hands her to me. I am pure joy. I stroke her hair. I feel the fabric of the pants, the tiny plastic shoes that come with her. I’ve never seen the movie Aladdin, unlike my cousin, who, even though she’s been in America less than me, already knows everything and has seen everything, but I love Jasmine.

“I want her,” I say.

My cousin yanks her away. “You can’t have her, she’s mine.”

“Can I borrow her,” I say, breathily. “No, no, no!” My cousin leaves the room in a huff. She is used to getting her way. She calls her mom, my aunt, who calls my mom. They break away from their adult conversation downstairs, about how the hell they’re going to do something in this new country, and come upstairs to powwow.

“Let her borrow the doll,” my aunt says. “No, no” my mom says, firmly. “Stop being a bad girl,” she tells me. “Be polite, be nice.” Only bad girls ask for others’ toys. Nice girls don’t say anything, no matter how much they want something.

“Ok,” I say. I don’t like when my mom reprimands me. I try to color inside the lines my whole life. “She wants it, she’s smaller,” my aunt says. “Let her have this doll!” “No, don’t be ridiculous, we’ll buy her her own doll,” my mom says. My mom is proud. We don’t have any money yet, not even for a $12 doll. But she’ll be damned if she lets me borrow my cousin’s.

I start whining. We’re both only children, and we’re at an impasse. My mom leads me away with promises of dessert and tea downstairs. My cousin looks on triumphantly, but just as I’m about to go down the stairs she says graciously, “You can come play with her on weekends.”  I am eight years old and we have moved away from Philadelphia because neither of my parents could find jobs there but now we have some jobs.

I am eight years old and we have moved away from Philadelphia because neither of my parents could find jobs there but now we have some jobs.

We live alone, without family, without anyone except ourselves for now, and it’s just the three of us in a tiny apartment, and it’s close to Christmas, I think, although we don’t celebrate it.

I am still short, pudgy, not incredibly attractive, and still wearing funny hand-me-downs, but those hand-me-downs are now being replaced with 80% markdown clothes from two seasons ago from discount outlets, but at least now I have more teeth and I can write short stories.I write hundreds of short stories, two pages long, about ponies and a town called Maytown where everyone is always happy and it’s always – you guessed it – May.

Now it’s dark, and we’re coming back from a walk along the river. We take a lot of walks along the river because Russians love walking, and because it’s free.

It starts to flurry, and now we’re in the car, driving home. “Can we go to McDonald’s, please?” I beg my parents. Everyone else in my class goes to McDonald’s. I’m the only one who’s never been. “No, we have dinner at home,” my mom starts to say. I want to go to McDonald’s because every American does, but more importantly, because they have Polly Pocket.

Everyone in my class has Polly Pocket dolls. They come in with them, take them out of their perfect Jansport backpacks, next to their Lunchables lunches, next to whatever else their parents bought them that weekend. I want a Polly Pocket with my Happy Meal so bad.

“No, we have dinner at home,” my mom says.

“Please?” I say. I try to think of how to say this like a good girl, even though my heart is pounding in my chest. I’ve never gotten up the nerve to ask this before, and I am terrified I’ll be turned down.

“No-” my mom starts to say, but my dad overrides her. “Let’s go,” he says, nodding to me. He knows.

We get there. We are at a loss for what to order, so we all order hamburgers without fries, because it’s cheaper. “But the hamburger doesn’t come with the Happy Meal-” I start to protest. “You’ll be fine without it,” my mom says. The happy meal is more expensive. I eye the meat on my tray. I don’t eat red meat. “Go ahead,” my mom says. “I’m not making you anything at home.”

I put up a fuss. I’m a picky eater. The only way my mom got me to eat in Russia was to show me pictures from a picture book while she shoved kasha in my mouth. Eventually she gave up. At eight, I don’t eat: red meat, pork, cheese, pizza, olives, pickles, beets, or cabbage. I am a constant headache to cook for. My mom makes two separate meals, and tonight she is not having it. She’s exhausted from her new job.

“Eat it,” she says. “Eat it,” my dad says, raising his voice. Through the sting of tears, I take a bite of the hamburger. It is disgusting, because it is red meat. I chew another leathery bite, looking over at the happy meal display menu with the Polly Pockets, picking out which one I would take. Later that night, my mom boils pasta, sighing over the pot.

Later, under the New Year’s tree, I find the Polly Pocket castle. It is the biggest Polly Pocket, better than any of my classmates’. It even has a battery switch where you can turn the lights on. I have never been happier in my life. I bring it in the next day. Bam, I put it down on my desk, and all the other little girls crowd around it. “Wow, I don’t have that one,” they say, and I beam with pride. I know.

I am ten or eleven, and ready for a computer. “You can’t have a computer,” my dad says. Computers are really expensive and you have to pick out all the parts from a paper catalog that comes to your house. You have to spend time configuring the memory, the hard drive, the monitor.

I am ten or eleven, and ready for a computer. “You can’t have a computer,” my dad says. Computers are really expensive and you have to pick out all the parts from a paper catalog that comes to your house. You have to spend time configuring the memory, the hard drive, the monitor.

We’re not ready for a computer, although when we get one next year, it will become my universe.

I’m not wearing hand-me-downs anymore. We buy all our clothes in stores,mostly from the clearance section, but still in real live department stores where everyone I know shops.

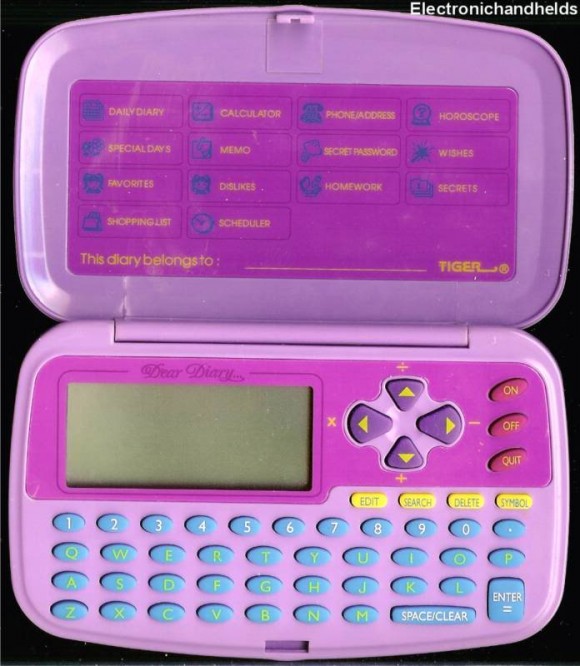

I set my sights lower, thumbing through the Toys R’ Us catalog. I can ask for things from the catalog now. I won’t get 90% of them, but I’ve built up a Barbie collection to rival anyone. I don’t have to share anything with anyone. The toys are all mine and I hoard them, greedy to own. In the catalog and on TV (we have cable tv now) I see it. Dear Diary. You can write anything you want in Dear Diary, and you can keep it with you. You can organize things. You can calculate things. And you can share secrets. I don’t know about the calculating, but I love writing, secrets, and being really organized. I want a Dear Diary.

But the Dear Diary is $40, so I have to save up some of my allowance for it, and we have to wait for what seems like months. “I just want to go to Toys R’ Us to look at it,” I say, burning with desire. “Ok,” says my dad, giving in. I look at the Dear Diary through its plastic clamshell packaging. “You still want it?” he asks. “You sure you don’t want something else?” Something cheaper, is the subtext. “No,” I say. “I want this.”

The day we buy it, I am giddy with joy. My own diary! When we get home, I rip it open. “Careful!” my dad warns. What if we have to return it? We have to keep the packaging in tact. I try to turn it on, but it doesn’t work. “Needs batteries,” I read in the pamphlet, my heart sinking. “We’ll get them tomorrow,” my dad says, but tomorrow is not soon enough for a kid with a diary, I need them RIGHT NOW.

So we go to the store again and shell out for super-tiny super-special electronics batteries. “Stupid toys, why don’t they come with batteries?” my dad grumbles, but I’m already absorbed in all the non-functionality of this non-internet-connected non-touch-screen PDA. I spend hours with it, typing my secrets and carrying it around the house. “Put that thing down, you look ridiculous,” my mom says,but she says it laughing. I am bursting with pride. I bring it in the next day. No one has a Dear Diary. I am the first one. No one else knows how to type.

***

I am 27, and I have my own job, my own house, and my own Macbook Pro, and sometimes I still can’t believe it. Thank you American toy industrial-complex, for the toys, to Buzzfeed for the trip down memory lane, and my parents, for the rest.