Strata 2016 and the rise of New Data

Intro

The last time I attended Strata + Hadoop World was in 2013. The conference was held at the New York Midtown Hilton for just a little over two days. Back then in the Stone Ages of Big Data, there was no Kafka, Spark, or Tensorflow.

Many teams were just beginning to explore realtime as a possibility, and the data formats we most associate with Hadoop today, Avro and Parquet, were just starting to gain traction as Apache projects.

Some of the ideas of that year’s conference focused on the nascent field of data science. But, 90% of the talks were just about correctly configuring Hadoop clusters so they didn’t break.

This year’s Strata was held in the enormous, newly-renovated Javits Center, fully booked out for a packed week of workshops, talks, and networking events, including a party aboard the Intrepid . From the sleek, red signage everywhere cavernous conference hall, to the large vendor displays, some so elaborate that you could probably run a small startup out of them for a couple weeks, it’s amazing, and even alarming, to see how quickly New Data (as I call it, since it encompasses more than just Big Data) has grown up.

Comparing 2013 and 2016 with word clouds

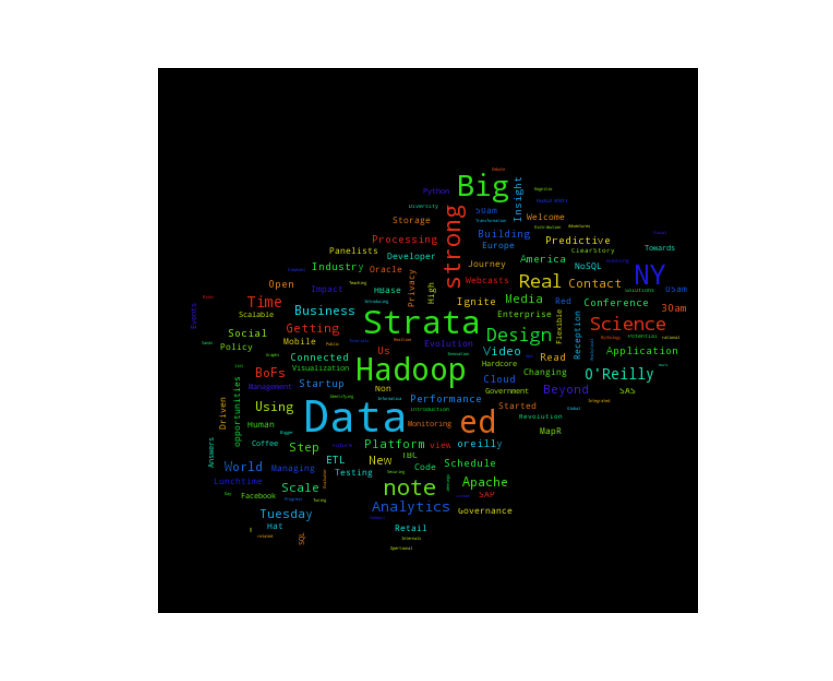

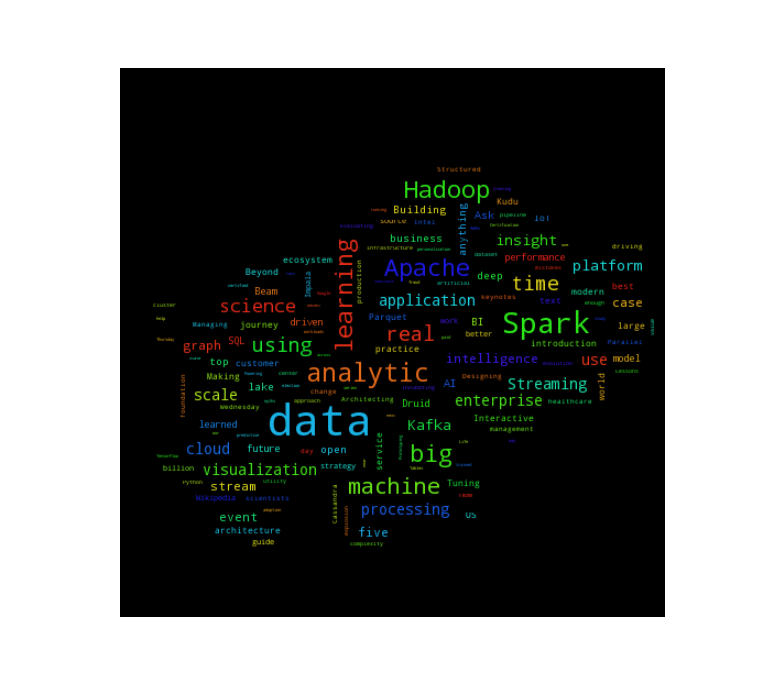

A quick glance at the titles of the talks confirms this. As I was working on this post, I wanted to verify that my impressions of the field from three years ago were correct, so I pulled the schedule of the first day of talks from 2013 and 2016, respectively. (all code for analysis can be found on my GitHub.)

What was interesting from the get-go was the different formatting. The 2013 schedule only had a way to download by viewing the source HTML and parsing that. I gamely started with Python’s Beautiful Soup , but found the hidden tags, nesting, and tables (and some elements that were seemingly exported from an ics file into HTML) too much even for my veteran scraping skills, so ended up using html2text, which still works really well, and parsing out the titles from there. Understandably, this has resulted in some noise that I’ve cleaned up with hideous regexes I am embarrassed to make public. The 2016 schedule was super-easy since I’d already pulled it through ical.

A quick glance shows just how mature the industry has become, even with the types of buzzwords that are now surging as talk titles: “platforms” and “machine learning” and “streaming”, versus “ETL”, “design” and “processing” in 2013.

2013:

2016:

Three New Data trends

Based on the word cloud and my observations at the conference, there are a couple of big trends currently going on in New Data.

Kafka and Spark

It’s amazing how huge Kafka and Spark, particularly Spark, have grown, from nothing in 2013, to becoming drivers of platform growth for companies - and salary growth for data scientists and engineers. In fact, the latest OReilly data science salary survey found that knowing Spark was one of the most significant contributors to an increased salary in 2016.

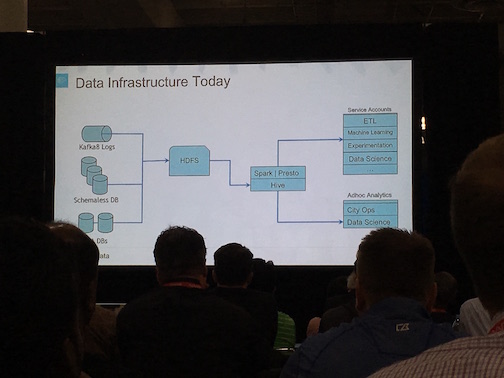

This is not surprising, given that Cloudera is officially headed to replace MapReduce with Spark on top of YARN in its distribution of Hadoop. The rise of these two tools means that the “average” new data ETL pipeline now looks something like this (sadly grainy) picture, which I took at a talk given by Uber, where Kafka feeds data into HDFS, where it immediately gets processed out further to data science applications. People have figured out that Hive (and even Presto to an extent) are slow, and have moved moved the processing downstream.

Realtime

The tremendous rise of Kafka and Spark have also given rise to realtime architectures that were simply not a possibility before. Twitter, a perennial favorite at these types of conferences, gave several talks about their new real-time streaming infrastructure with Heron, but social media companies relying on distributed systems to move massive amounts of pictures and text has been standard operating procedure for some time now.

What was particularly interesting was watching companies like Uber (and Amazon), who have physical inventory that they need to move around, talk about working through both the technology of massive distributed systems at the digital level, but also making sure that actions are reflected properly in the real world. Today, the number of companies trying to connect the digital to the physical is astounding. The focus on hardware, or “real-world” applications is only growing, particularly since YCombinator, which sets trends in the startup and tech industries, has started focusing on hardware.

Trying to make sense of all the data

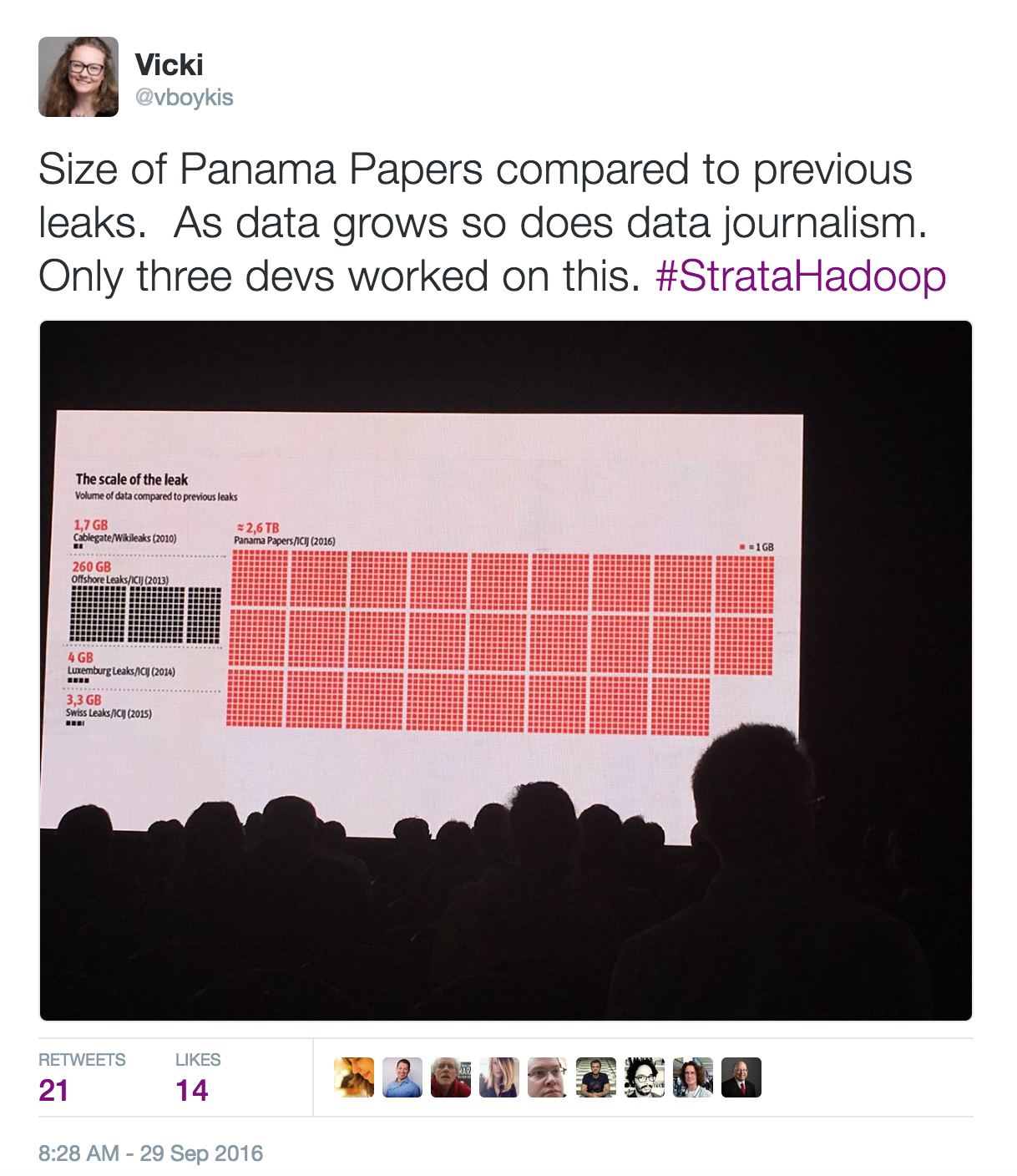

Something that has not changed, though, is that, no matter how large or small the data is, people need tools and mental models to make sense of it. And data is only getting larger. A talk that astounded me was Mar Caba speaking about the Panama Leaks. As a non-profit, the center investigating the papers only had three developers to work on almost 3 TB of data.

In this case, it’s both about the size of the data, and the amount of industry knowledge needed to ask the right questions (how offshore bank accounts work, politics of different countries, how to come up with newsworthy data points.) But at most companies, even if they don’t have as much data, the struggle is, as it always has been, to understand what the data is telling them. In 2013, platforms like Platfora and Cloudera’s Manager interface for writing Hive queries were trying to recreate the business intelligence environment that came before big data.

Today, companies are hiring as many as nine data scientists (per a Pinterest presentation) to understand the trends they’re seeing and to be able to make product decisions. Sometimes, as that presentation shows, even scientific-minded individuals highly trained in technology, can come to radically different conclusions.

A couple more presentations in this vein, including a talk called “Why should I trust you? Explaining the predictions of machine-learning models” makes me believe that while we are starting to reach tool maturity in data engineering, data science is still in the very nascent stages and has a while to go before processes and frameworks are fully-established.

Interestingly enough, even as data science grows and the questions around it become important in most industries, Strata is becoming less important for data scientists to attend. All of the ones I surveyed saw it as “too big” and “too commercial” and “not technical enough”, in favor of smaller, local meetups on specific technologies, conferences like MMDS, Spark Summit, and SciPy.

The New Data culture

In many ways, New Data is more entrenched, and yet more unsure of itself than ever before.

In one of the keynote talks on the second day, Alistair Croll, said something that really struck me: Usually technology is used “on” us, before it is used “by” us, and his example of this was the current wave of machine learning and AI algorithms that sift through the data we provide them, instead of us having the agency to have access to the data ourselves.

For the past five years or so, the New Data industry has been all about ingesting, egressing, processing, crunching, building models, and trying to get ahead of the massive deluge of data we now have access to, without stopping to think about whether we need the data and what it means.

The ongoing fallout of Edward Snowden’s data revelations have made many citizens question what the government is storing. But, they have also impacted companies and individual technologists. Maciej Ceglowski, who owns Pinboard, has been giving talks on this issue, including a keynote he gave at Strata in 2015, in which he encouraged companies to look at data as a liability, in that the more you have to store, the harder it gets to keep it secret and safe.

Several of the keynotes at Strata this year focused on the same themes of data as a tool for social responsibility (a theme echoes in the industry as a whole by practitioners like Cathy O Neil, who talks of ethical algorithms), and on the importance of not trusting data that has been pre-analyzed (Jill Lepore’s excellent talk on why polls are bad..

In this way, while companies continue building out tools for speed and scale, business stakeholders are also starting consider the implications of what they build and ask for, and it will be interesting to see where the give-and-take of “build it because we need it and we can” intersects with “how does this benefit the organization or society.”

I’m excited to see where this push and pull takes New Data this year, and what kinds of talks will be at Strata in 2019.