What should you think about when using Facebook?

Courbet, The Winnowers

TL;DR: Facebook collects data about you in hundreds of ways, across numerous channels. It’s very hard to opt out, but by reading about what they collect, you can understand the risks of the platform and choose to be more restrictive with your Facebook usage.

Translations

- Dutch translation here Big thank you to Ben!

- Portuguese translation here. Thank you to Ibrahim!

- Ukranian translation here

- French translation here

- Russian translation here

- Chinese translation here

Contents:

- How Facebook collects data

- What does Facebook know before you post?

- After you post: what Facebook collects about you

- What does Facebook do with your data internally?

- What relationship does Facebook have with marketers?

- What data does Facebook give to the government?

- What does Facebook track after you leave Facebook?

- What should I think about when I use Facebook?

- What should I do if I don’t want Facebook to have my data?

Facebook, for better or worse, has become our living room, our third place online. It’s the place where we talk to friends, sound off on the news, organize events, grieve over people we’ve lost, celebrate babies, engagements, new jobs, new haircuts, and vacations.

Facebook, the platform, has taken up such a large part of our mindshare and has started to serve as our pensieve. Because of this, it’s important to understand what Facebook, the company, is doing with our hopes, dreams, political statements, and baby pictures once it gets them.

And gets them it does. In 2014, Facebook engineers wrote that they have about 600 terabytes of data coming in on a daily basis.

For perspective, the size of War and Peace, the text is 3.1 megabytes. The 1966 Soviet movie version of War and Peace the movie is 7 hours long, or 8 gigabytes in size.

So people are uploading the equivalent of 193 million copies of War and Peace books, or 75,000 copies of War and Peace movies, every single day.

Facebook’s Data Policy outlines what it collects and what it does with that data. However, like most companies, it leaves out the actual points that tell customers what exactly is happening.

Frustrated by the constant speculation of where those keystrokes are going for every status update I write, I decided to do some research. All of the information below is taken from tech trade press, academic publications, and what I was able to see on the client side as a Facebook user. I’ve added to this post my own interpretations as a data professional working with user data for 10+ years.

If anyone working at Facebook wants to add corrections to this post, I would love to hear from them that they’re not collecting and processing as much as everything below says they are.

How Facebook collects data

To understand how Facebook data collection works, I drew a (very, very) simplified diagram. The user enters data into the UI (the application). This is the front end.

The data is then collected into Facebook’s database (of which they have many.) This is the backend.

The data that users see in the front-end is a subset of the backend data.

If you’re interested in more of the technical specs, there are lots of architecture diagrams on the googles. Facebook is at the cutting edge of working with big data, and their stack includes Hive, Hadoop, HBase, BigPipe, MySQL, Memcached, Thrift, and much, much more. All of this is housed in lots of massive data centers, such as one in Prineville, Oregon.

What does Facebook know before you post?

Facebook data collection potentially begins before you press “POST”. As you are crafting your message, Facebook collects your keystrokes.

Facebook has previously used to use this data to study self-censorship (PDF.)

The researchers write,

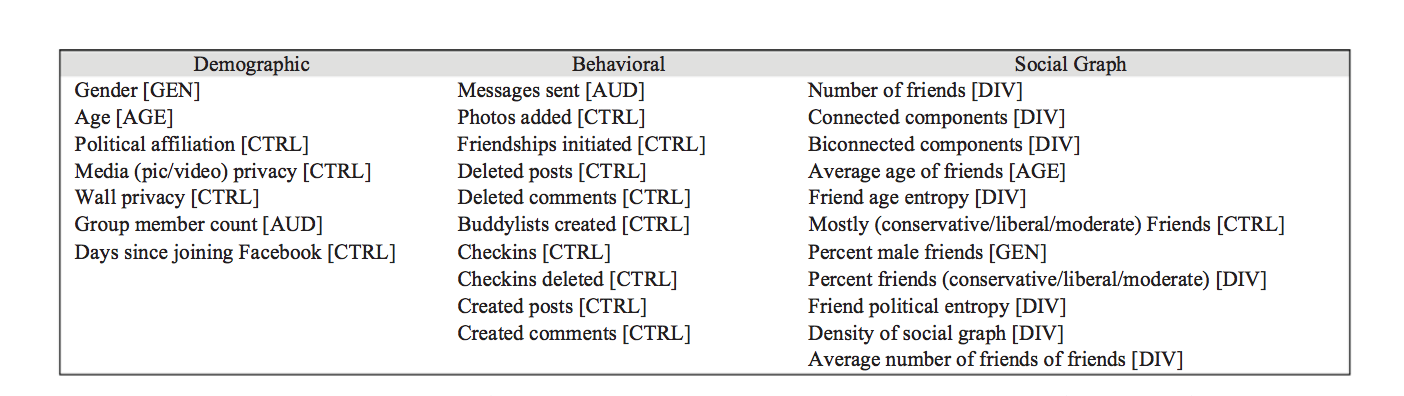

We report results from an exploratory analysis examining “last-minute” self-censorship, or content that is filtered after being written, on Facebook. We collected data from 3.9 million users over 17 days and associate self-censorship behavior with features describing users, their social graph, and the interactions between them.

Meaning, that if you posted something like, “I just HATE my boss. He drives me NUTS,” and at the last minute demurred and wrote something like, “Man, work is crazy right now,” Facebook still knows what you typed before you hit delete.

Here are the data points they used to conduct their study:

Something of interest here is: deleted posts, deleted comments, and deleted checkins. Just like there’s no guarantee that things you didn’t write won’t be stored, there’s no guarantee that,if you delete data, the data is actually deleted.

So, even if you delete a post, Facebook keeps track of that post. Facebook keeps track of the metadata, or the data about your data. For example, the data of a phone call is what you actually talked about. The metadata is when you called, where you called from, how long you called for, etc.

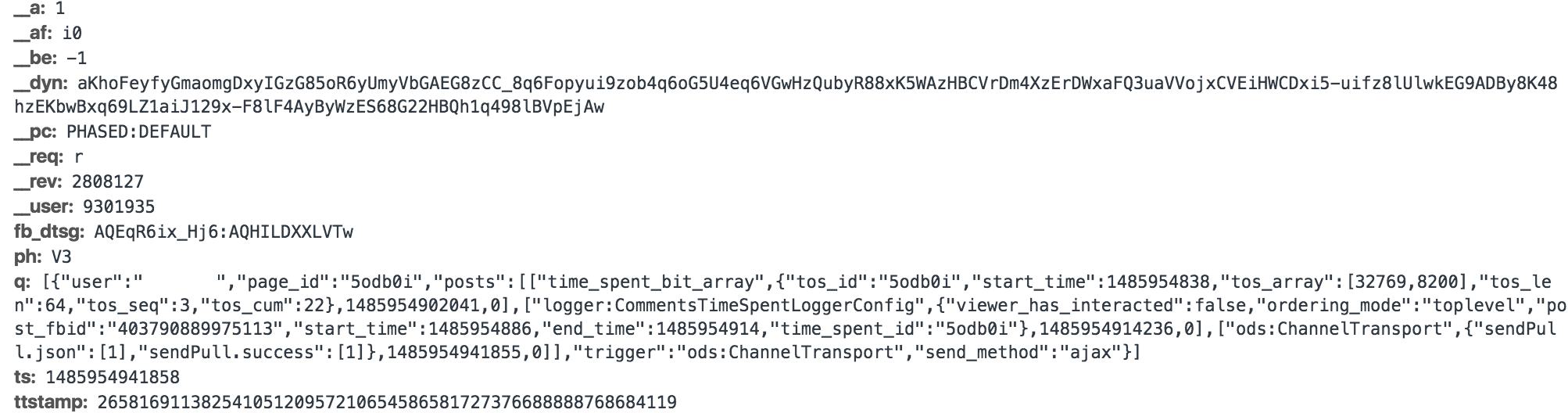

For Facebook, metadata is just as important as real data, and it uses that data to make extrapolations about who you are. Using Developer Tools on Chrome, it’s relatively easy to see the plethora of data passed to Facebook from your client to their backend via xhr. I’m not a front-end ninja (but would actually love to talk to one to see what else we could pull), but from one image, you can see that facebook is tracking the time you spend doing …something? Not clear what, but it probably figures into time spent on the site, which Facebook reports out.

Incidentally, this is true for account deletions, as well.

Since Facebook has so many systems and so many places where data can co-mingle, as a former Facebook consultant writes,

To answer the first part of your question, “Could you pay Facebook to properly delete all your information?”, assuming “properly” means completely wipe away any trace that you ever existed on Facebook, the answer is no.

Similarly, with deleted posts, there’s no guarantee that Facebook doesn’t even keep the post itself on the backend database; just that it won’t show up on the client-facing site.

Once you actually do write a post, upload a picture, or change any information, everything is absolutely fair game for Facebook’s internal use in research, reselling to marketing aggregators like Acxiom, and to give to the United States government, through agencies like the NSA, through its PRISM program.

After you post: what Facebook collects about you

Facebook obviously collects all of the data you volunteer to them: your political affiliation, your workplace, favorite movies, favorite books, places you’ve checked in, comments you’ve made, and any and all reactions to posts. Facebook allows you to download a subset of the data they have in their database about you.

In my personal subset, I was able to see:

- photos I uploaded and photos tagged of me

- videos

- everything I’ve ever posted to my own timeline (including events I indicated interest in, what people posted to my timeline, memories shared,)

- friends and when I became friends with them

- All of my private messages

- Events I’ve attended

- Every single device I’ve ever logged in from

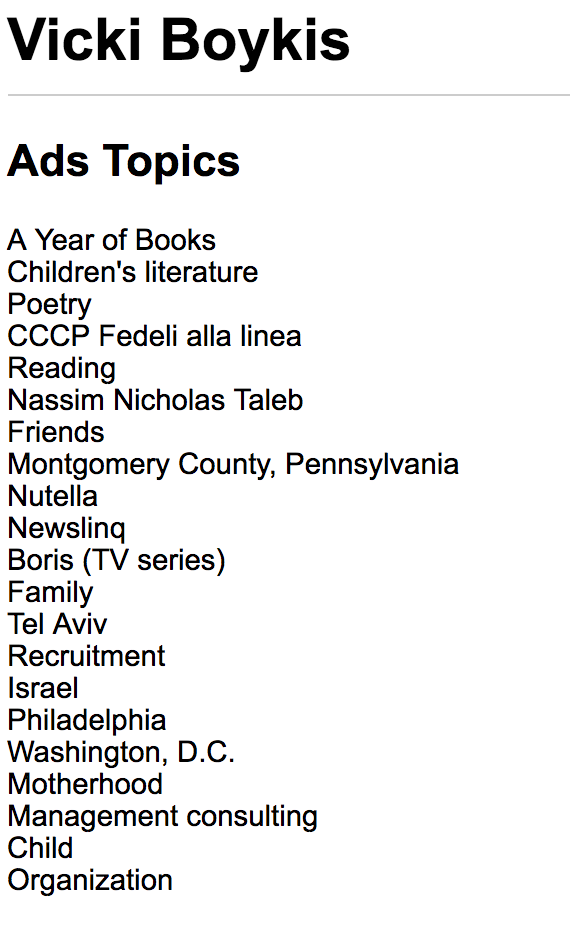

And, which ads I would be interested in. This is not something I put in myself. This is something Facebook generated algorithmically based on every single thing I’ve posted:

But we’ll get to that in the advertising section.

In addition to the data and metadata, Facebook also tracks intent. One of the ways it does this has already been explored: unposted statuses. Another is heatmap tracking of engagement during videos.

In addition to everything it knows about you, it also knows everything about your friendships. All of this is to say, Facebook knows quite a bit about you, even if you don’t flesh out your profile or actively post to the site.

What does Facebook do with your data internally?

Facebook does quite a few things with the data it collects.

First, it conducts simple queries on information to improve site performance or to do business reporting (for example, what was the uptime on the site, how many users does Facebook have, how much ad revenue did it make today?) This is true for every single company anywhere.

However, with Facebook, there’s a twist. It has an entire engineering team dedicated to building tools to make data easier to query with SQL-like language built on top of Hadoop, with Hive, and, although Facebook claims that access is strictly controlled, some accounts say otherwise.

Paavo Siljamäki, director at the record label Anjunabeats, brought attention to the issue when he posted, on Facebook, that on a visit to the company’s L.A. office an employee was easily able to access his account without asking him for his password.

Here are some more accounts of Facebook employees accessing private data.

Second, Facebook conducts academic research by using its users as guinea pigs, a fact that is not mentioned in the Data Policy, which is interesting, given that on Facebook Research’s main page, a header reads, “At Facebook, research permeates everything we do.”

It has a pretty large data science team (41 people at last count. ) To put in perspective, a similarly-sized company of 15,000 might have 5 data scientists, if it’s really trying to aggressively push a data science research program.

However, as late as 2014, there was no process to keep check on what kind of data was accessed, and for what kind of studies. As a former Facebook data scientist wrote,

While I was at Facebook, there was no institutional review board that scrutinized the decision to run an experiment for internal purposes. Once someone had a result that they decided they wanted to submit for publication to a journal, there definitely was a back and forth with PR and legal over what could be published. If you want to run a test to see if people will click on a green button instead of a blue button you don’t need approval. In the same way, if you want to test a new ad targeting system to see if people click on more ads and revenue goes up, you don’t need institutional approval.

While he goes on to note that this is normal at most software-as-a-service companies, most SaaS companies also don’t granularly collect the most intimate details of peoples’ lives over the course of over a decade.

He goes on to note,

The fundamental purpose of most people at Facebook working on data is to influence and alter people’s moods and behaviour. They are doing it all the time to make you like stories more, to click on more ads, to spend more time on the site.

While this is understandably a goal of most websites, you may want to think twice about spending more than 40 minutes a day on a site that is aimed to undermine you emotionally.

In addition to Facebook mining text and studying our emotions, it also manipulates them.

The News Feed is prime for manipulation, specifically because Facebook has engineered it to be as engaging as possible: it’s synaptic sugar to our nervous systems. Facebook wants to make sure you spend as much time on the Feed as possible, and to this end will spend more time surfacing pictures of babies and other happy things, as well as news items that generate controversy and outrage, over normal statuses like “I had breakfast today.” that don’t garner reactions.

This is how today’s so-called filter bubble got started. Because people click on things that are interesting to them, Facebook shows only things that engage people, meaning that other points of view, friends, and images, are omitted from a person’s Facebook Feed diet. For an excellent example of how this works, check out Red Feed, Blue Feed, which shows how differently liberal and conservative Facebook feeds look.

What else are they studying? The rate at which gay people come out, to start with. How do they know this? “Over the past year, approximately 800,000 Americans updated their profile to express a same-gender attraction or custom gender.”

A lot of Facebook’s studies center on graph theory; that is, how we relate to our friends; in other words, it’s performing anthropological research on subjects that have never consented to it.

For example, recently, the data science team published a study on the social ties of immigrant communities in the United States, where the researchers use the following data:

We limited our analyses to aggregate measures based on deidentified social network data for people from the U.S. who used Facebook at least once in the 30 days prior to the analyses. We used the home town specified by the person in their profile to determine the person’s home country.

Furthermore, we also restrict our analysis to people with at least two friends currently living in their home country and another two friends currently living in the United States. Our results are based on a sample of more than 10 million people who satisfy these criteria. Throughout the paper, all references to people on Facebook will implicitly assume these constraints

These are the studies we know to be public. What else are they doing under wraps?

Another thing Facebook likes to study, is, understandably, faces. Every time you tag yourself in a picture, Facebook recognizes you and will adjust accordingly.

Facebook encourages users to “tag” people in photographs they upload in their personal posts and the social network stores the collected information. The company uses a program it calls DeepFace to match other photos of a person.

This program, called DeepFace, is a fantastic way to get more accurate tags. This is also a fantastic way to violate someone’s privacy. For example, what if you don’t want to be tagged? Like, if you’re at a government protest? Or, even, simply, if you went to a concert with one friend instead of the other and didn’t want to let one know?

Unfortunately, privacy of movement soon won’t be an option. Facebook is working on ways to identify people hidden in pictures. The Facebook paper on DeepFace notes that, “The social and cultural implications of face recognition technologies are far reaching”, and yet does not at all talk about the possible privacy dangers with having your face tagged, for example,

“We could soon have security cameras in stores that identify people as they shop,” she says.

How do they know all of this?

Because this is all data we give them voluntarily, with each time we post a status update, each time we upload a picture and tag it, each time we message with a friend, check in at a location, with each single time we log into Facebook and the system generates a message to be saved to the database, “Hey, this person is now in the Facebook universe”, which now includes Whatsapp and Instagram.

Shadow profiles

What does Facebook do if you don’t share as much data as it likes? It creates shadow profiles, or a “a collection of data that Facebook has collected about you that you didn’t provide yourself.”

As the article states,

Even if you never provided them, Facebook very likely has your alternate email addresses, your phone numbers, and your home address – all helpfully supplied by friends who are trying to find you and connect.

Even worse, Facebook collects, basically..your face.

One recent lawsuit focuses not on email addresses or phone numbers, but instead “face templates”: whenever a user uploads a photo, Facebook scans all the faces and creates a “digital biometric template”.

All this would be concerning even if Facebook collected the data just for itself. But then there are the external vendors.

What relationship does Facebook have with marketers?

Facebook’s Data Policy notes that it partners with other vendors to collect data about you:

We receive information about you and your activities on and off Facebook from third-party partners, such as information from a partner when we jointly offer services or from an advertiser about your experiences or interactions with them.

It collects “roughly 29,000 demographic indicators and about 98 percent of them are based on users’ activity on Facebook.”

Roughly 600 data points, meanwhile, reportedly come from independent data brokers such as Experian, Acxiom and others. Users reportedly don’t get access to this demographic data obtained from third parties.

In addition to collecting all the details you volunteer about yourself, such as full legal name, birth date, hobbies, religion, and all the places you ever went to school or worked, Facebook also makes assumptions about things it doesn’t know so it can [share that data with Acxiom, and other advertising powerbrokers to more effectively target to you.

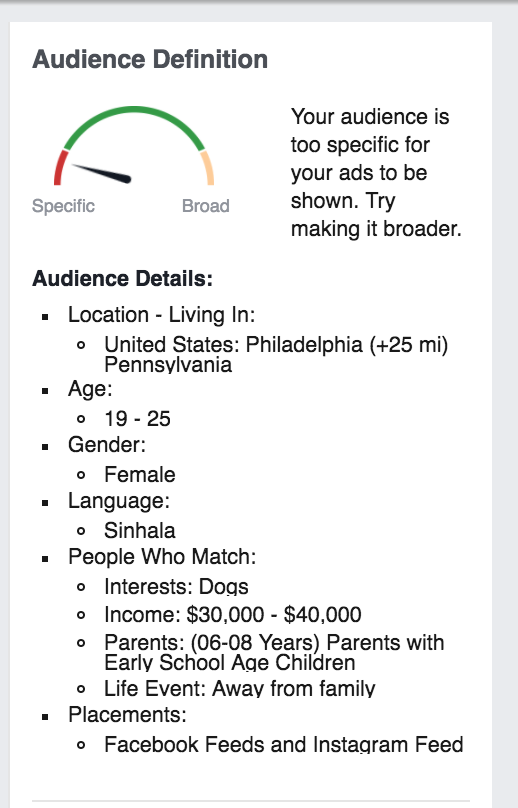

For example: household income, which it then uses to create a data profile to sell to marketers, who are, after all, its paying customers. Marketers can then buy fine-grained profiles that include any and all of the following:

Location, Age, Generation, Gender, Language, Education level, Field of study, School, Ethnic affinity, Income and net worth, Home ownership and type, Home value, Property size, Square footage of home, Year home was built, Household composition.

How does Facebook know this? By making some assumptions about you based on the data it knows and what it gets from Experian and the like.

This data can then be used to target Facebook users in the form of ads. The kinds of targeting you can do on Facebook tells you a lot about the data they keep behind the scenes. For example, you can not only target by location/age/gender/language, you can also do hobbies and life stages (i.e. just engaged, engaged 6 months ago, children in early school age). It’s possible to target someone this narrowly and still it have reach a certain number of people (in my example, it was 100-200).

This data can then be resold downstream, where it’s blended with other data that exists about you through credit cards and other marketing sources, to create sites like this that will try to build out a full profile of you. There is no easy way to get out of this, because once data is created, it’s much harder to delete. This is why one of the primary concerns of privacy activists is getting companies to bulk-delete data after a certain period.

Facebook also has the right to use your, and your child’s if they’re under 18, pictures in ads.

What data does Facebook give to the government?

We don’t know everything that Facebook gives to the government. Facebook does have a Government Reports page, which hasn’t been updated since June 2016. We do know, however, that government is asking for more and more information.

That data leads to a report which shows how much data was accessed and how many users were impacted, but doesn’t say anything additionally about the kind of information given, or what kind of agencies were accessing it (local, state, FBI/NSA).

| Country | Total Requests for User Data | Total User Accounts Referenced | Total Percentage of Requests Where Some Data Produced | Content Restrictions | Preservations Requested | Users/Accounts Preserved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 23,854 | 38,951 | 80.65% | 0 | 31893 | 56714 |

Mark Zuckerberg even issued a statement, saying,

Facebook is not and has never been part of any program to give the US or any other government direct access to our servers. We have never received a blanket request or court order from any government agency asking for information or metadata in bulk, like the one Verizon reportedly received. And if we did, we would fight it aggressively. We hadn’t even heard of PRISM before yesterday.

Again, here it’s important to read between the lines. Direct access to servers is not necessary to send bulk files. It’s also not necessary to know about PRISM by that name.

It’s also hard to know whether the NSA is collecting data from Facebook in some other way. In Europe, at least, lawsuits are underway on this issue.

But for now, just assume this surveillance is ongoing.

What does Facebook track after you leave Facebook?

Outside of Facebook.com, Facebook tracks you through Single-Sign On.

If you log out, Facebook also tracks you through cookies. As their privacy policy states,

We collect information when you visit or use third-party websites and apps that use our services. This includes information about the websites and apps you visit, your use of our services on those websites and apps, as well as information the developer or publisher of the app or website provides to you or us.

Facebook also is trying to track, or already tracking, how your cursor moves across the screen.

As early as 2011, it also began tracking how you move across the web if you’re still logged into Facebook.

Facebook keeps track of where you are on the web after logging in, without your consent. Nik Cubrilovic dug a little deeper, and discovered that Facebook can still track where you are, even if you log out. Facebook, for its part, has denied the claims.

It’s safe to say it collects your browsing history to enrich ads.

What should I think about when I use Facebook?

What does this all mean? Essentially, it means that every single thing you do on Facebook, and if you’re logged in, on other websites, is potentially tracked by Facebook, and saved on their servers.

To be clear, every company currently does some form of this tracking of users. There would simply be no other way to measure operations. But Facebook has quite clearly been tiptoeing outside the bounds of what is ethically acceptable data business practices for a while. Even if Facebook is currently not doing some of the things I mentioned (capturing pre-posts, messing with the News Feed,) they’re doing very similar work and there’s no guarantee of privacy or not being used in an experiment. It also means if you’re not active on Facebook, you could still be tracked.

Every single like you gave a post, every friend you added, every place you checked in, every product category you clicked on, every photo, is saved to Facebook and aggregated.

Aggregated how? Hard to say. Maybe as part of a social experiment. Maybe your information is being passed over to government agencies. Maybe individual employees at Facebook that don’t necessarily have the right permissions can access your page and see your employment history. Maybe that same employment history is being sent over to insurance companies.

This includes all private groups, all closed groups, and all messages. And, as Facebook points out, There is no such thing as privacy on Facebook.

Essentially, what this means is that you need to go into Facebook assuming every single thing you do will be made public, or could be used for advertising, or analyzed by a government agency.

What should I do if I don’t want Facebook to have my data?

Facebook started as a way for college students to connect with each other, and has eventually gotten to the point where it’s changing people’s behavior, tracking their usage, and possibly aggregating information for the government.

The problem is that each person, whether he or she uses Facebook or not, is implicated in its system of tracking, relationship tagging, and shadow profiling. But this is particularly true if you are an active Facebook user.

So the most important thing to is to be aware that this is going on and give Facebook as little data as possible.

Here is a list of things I do to minimize my exposure to Facebook.

Not everyone will do what I do. But the most important thing is that, even if you decide to continue using Facebook as you’ve done, you’re aware of what Facebook is doing with your data and are empowered to make the tradeoffs that come with being social.

- Don’t post excessive personal information.

- Don’t post any pictures of your children, especially if they’re at an age where they can’t consent to it.

- Log out of Facebook when you’re done with it on your browser. Use a separate browser for Facebook and a separate one for everything else.

- Use ad blockers

- Don’t use Facebook, particularly Messenger to organize or attend political events. If you need to organize, use Facebook as a starting point, and then get on another platform. Recommended Platforms: Signal is the gold standard for private chat right now. Whatsapp is ok for group chat, but, I don’t recommend because it’s tied to Facebook’s system of metadata. Telegram is also good, but not as good because it’s closed source. Again, it depends on your level of risk. Here is more on these platforms.

- Don’t install the Facebook app on your phone. It asks for a lot of crazy permissions.

- Don’t install Messenger on your phone. Use the mobile site. Messenger is blocked on mobile now, so use the workaround of enabling the desktop site on your browser.

It’s very sad that a social network that’s done so much good is also the single worst thing about the internet, but until people leave the platform or apply some kind of economic pressure on it, nothing will change.

For my part, something I personally as a data professional have done is send Facebook recruiters that email me the following message:

Dear Recruiter,

The way Facebook collects and uses data, including:

- reselling user data to advertising companies like Acxiom,

- tracking user browsing,

- facial recognition,

- the creation of shadow profiles,

- and particularly social science experimentation like emotional contagion*,

- the use of algorithms in the News Feed to create a filter bubble

- and, most importantly, give access of the wealth of data Facebook has made available to government bodies like the NSA

has made me not only strongly oppose working there but has made me strongly evaluate my usage of Facebook, because I never know how every keystroke I enter into the system will be used.

If Facebook as a company is committed to changing direction and

- using data to fight some of these issues

- actively working on ways to delete unnecessary data*

- actively working on private, secure communication that is not party to government interference

- and actively working on ways to prevent private customer data from being shared to unnecessary third parties

I would love to know.

Sincerely,

Vicki

We are social animals, and we are wired to want to connect, want approval, want to share, and want to organize on the platform where everyone else is, and this, for now, is in Facebook’s advantage. Additionally, it’s hard to say that Facebook is all bad: it does connect people, it has helped organize meetups and events, and it does make the world more interconnected.

But, as Facebook’s users, we and our data are its product. And, as we understand more about how this data is being used, we can still play on Facebook’s playground, by its rules, but be a little smarter about it.

#social #data #web dev #engineering #computing history