Being a woman in programming in the Soviet Union

Vicki’s note: A couple weeks ago, I saw a really interesting clip on Twitter that showed students in the Soviet Union learning to program using pen and paper. My mom has often told stories about how she learned to program the same way, and I shared the tweet. Marie Hicks, a tech historian, reached out and asked if my mom would want to write about her experiences, and she did.

In 1976, after eight years in the Soviet education system, I graduated the equivalent of middle school. Afterwards, I could choose to go for two more years, which would earn me a high school diploma, and then do three years of college, which would get me a diploma in “higher education.”

Or, I could go for the equivalent of a blend of an associate and bachelor’s degree, with an emphasis on vocational skills. This option took four years.

I went with the second option, mainly because it was common knowledge in the Soviet Union at the time that there was a restrictive quota for Jews applying to the five-year college program, which almost certainly meant that I, as a Jew, wouldn’t get in. I didn’t want to risk it.

My best friend at the time proposed that we take the entrance exams to attend Nizhniy Novgorod Industrial and Economic College. (At that time, it was known as Gorky Industrial and Economic College - the city, originally named for famous poet Maxim Gorky, was renamed in the 1990s after the fall of the Soviet Union.)

They had a program called “Programming for high-speed computing machines.” Since I got good grades in math and geometry, this looked like I’d be able to get in. It also didn’t hurt that my aunt, a very good seamstress and dressmaker, sewed several dresses specifically for the school’s chief accountant, who was involved in enrollment decisions. So I got in.

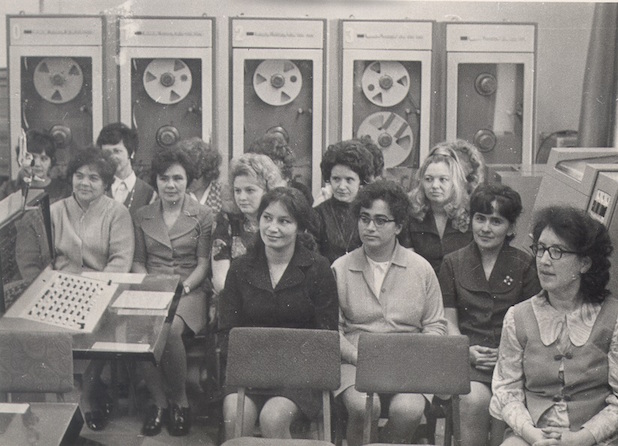

What’s interesting is that from the almost sixty students accepted into the program that year, all of them were female. It was the same for the class before us, and for the class after us. Later, after I started working the Soviet Union, and even in the United States in the early 1990s, I understood that this was a trend. I’d say that 70% of the programmers I encountered in the IT industry were female. The males were mostly in middle and upper management.

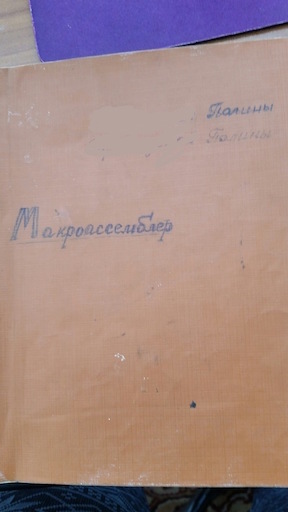

My mom’s code notebook, with her name and “Macroassembler” on it.

We started what would be considered our major concentration courses during the second year. Along with programming, there were a lot of related classes: “Computing Appliances and Their Organization”, “Electro Technology”, “Algorithms of Numerical Methods,” and a lot of math that included integral and differential calculations. But programming was the main course, and we spent the most hours on it.

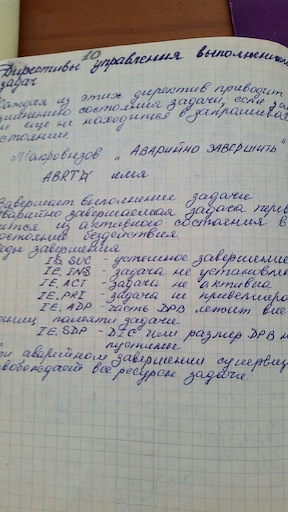

Notes on programming - Heading is “Directives (Commands) for job control implementation”, covering the ABRT command

In the programming classes, we studied programming the “dry” way: using paper, pencil and eraser. In fact, this method was so important that students who forgot their pencils were sent to the main office to ask for one. It was extremely embarrassing, and we learned quickly not to forget them.

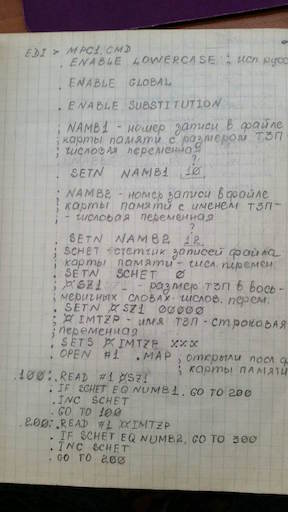

Paper and pencil code for opening a file in Macroassembler

Every semester we would take a new programming language to learn. We learned Algol, Fortran,and PL/1. We would learn from simplest commands to loop organization, function and sub-function programming, multi-dimensional array processing, and more.

After mastering the basics, we would take exams, which were logical computing tasks to code in this specific language.

At some point midway through the program, our school bought the very first physical computer I ever saw : the Nairi. The programming language was AP, which was one of the few computer languages with Russian keywords.

Then, we started taking labs. It was terrifying experience. You had to type your program in entering device which basically was a typewriter connected to a huge computer. The programs looked like step-by-step instructions, and if you made even one mistake you had to start all over again. To code a solution for a linear algebraic equation usually would take 10 - 12 steps.

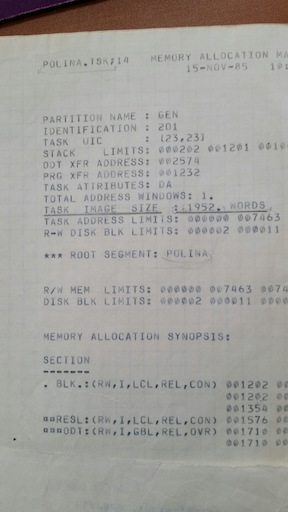

Program output in Macroassembler (“I was so creative with my program names,” jokes my mom.)

Our teacher used to go for one week of “practice work and curriculum development,” to a serious IT shop with more advanced machines every once in a while. At that time, the heavy computing power was in the ES Series, produced by Soviet bloc countries.

These machines were clones of the IBM 360. They worked with punch cards and punch tapes. She would bring back tons of papers with printed code and debugging comments for us to learn in classroom.

After two and half years of rigorous study using pencil and paper, we had six months of practice. Most of the time it was one of several scientific research institutes existed in Nizhny Novgorod. I went to an institute that was oriented towards the auto industry.

I graduate with title “Programmer-Technician”. Most of the girls from my class took computer operator jobs, but I did not want to settle. I continued my education at Lobachevsky State University, named after Lobachevsky, the famous Russian mathematician. Since I was taking evening classes, it took me six years to graduate.

I wrote a lot about my first college because now looking back I realize that this is where I really learned to code and developed my programming skills. At the State University, we took a huge amount of unnecessary courses. The only useful one was professional English. After this course I could read technical documentation in English without issues.

My final university degree was equivalent to a US master’s in Computer Science. The actual major was called “Computational Mathematics and Cybernetics”.

In total I worked for about seven years in the USSR as computer programmer, from 1982 to 1989. Technology changed rapidly, even there. I started out writing programs on special blanks for punch card machines using a Russian version of Assembler. To maximize performance, we would leave stacks of our punch cards for nightly processing.

After a couple years, we got terminals with keyboards. First they were installed in the same room where main computer was. Initially, there were not enough terminals and “machine time” was evenly divided between all of the programmers during the day.

Then, the terminals started to appear in the same room where programmers were. The displays were small, with black background and green font. We were now working in the terminal.

The languages were also changing. I switched to C and had to get hands-on training. I did not know then, but I picked profession where things are constantly moving. The most I’ve ever worked with the same software was for about three years.

In 1991, we emigrated to the States. I had to quit my job two years before to avoid any issues with the Soviet government. Every programmer I knew had to sign a special form commanding them to keep state secrets. Such a signature could prevent us from getting exit visas.

When I arrived in the US, I worried I had fallen behind. To refresh my skills and to become more marketable, I had to take programming course for six months. It was the then-popular mix of COBOL, DB2, JCL etc.

The main differences between USA and the USSR was the level at which computers were incorporated in every day life. In the USSR, they were still a novelty. There were not a lot of practical usage. Some of the reasons were planed organization of economy, politicized approach to science. Cybernetics was considered “capitalist” discovery and was in exile in 1950s. In the United States, computers were already widely in use, and even in consumer settings.

The other difference is gender of this profession. In the United States, it is more male-dominated. In Russia as I was starting my professional life, it was considered more of a female occupation. In both programs I studied , girls represented 100% of the class. Guys would go for something that was considered more masculine. These choices included majors like construction engineering and mechanical engineering.

Now, things have changed in Russia. Average salary for software developer in Moscow is around $21K annually, versus $10K average salary for Russia as a whole. It, like in the United States, has become a male-dominated field.

In conclusion, I have to say I picked the good profession to be in. Although I constantly have to learn new things, I’ve never had to worry about being employed. When I did go through a layoff, I was able to find a job very quickly. It is also a good paying job. I was very lucky compared to other immigrants, who had to study programming from scratch.

#computing history #career advice #community #engineering culture #writing