Should you replace Hadoop with your laptop?

Vicki’s note: I’ve given this talk at Data Philly at Sidecar and Software as Craft at Promptworks. To see all the slides and the code, check out the original deck here.

This talk is not meant to discourage you from pursuing distributed, NoSQL systems, but to get you to think about tradeoffs. Every technical choice is a tradeoff for another one, and it’s important to understand what you’re keeping and giving up in each scenario.

The video for the talk is here.

I’ve worked on three different Hadoop projects across three different companies over the past five years. It’s been interesting to see Hadoop go from a fledgeling technology, to one that’s going through its second round of architecture with the implementation of YARN in 2012, and now Spark. Many startups are rethinking their first round of Hadoop architecture, but what’s also cool is that Hadoop is just now getting to the point of really large-scale enterprise-level implementations, as well.

Some of the implementations I’ve seen have been really great examples of use cases for Hadoop, and some haven’t. As others have pointed out, you don’t always need Hadoop.

This talk is about exploring the idea of how far you can go with a single-node machine, aka your laptop, before moving to distributed, or even relational systems.

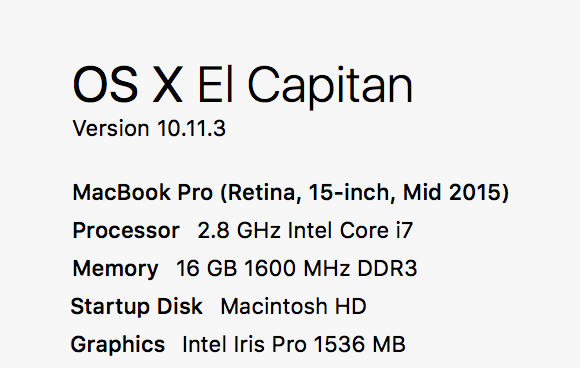

It turns out, you can go pretty far just doing big data analysis on a laptop with decent specs. All of my analysis for this talk was done on a mid-2015 Macbook Pro with 2.8 GHz Intel Core i7 processor and 16 GB of RAM.

There used to be a website up a couple years ago, which doesn’t exist anymore, called yourdatafitsinram.com, where you could enter the amount of data you want to store or process, and the site would tell you if you needed a distributed system. Most of the times, even in cases up to a terabyte, the site would tell you to buy a beefy standalone Dell commodity server.

I’ve taken the same idea here, based on what I’ve seen in industry and conversations with other smart people, to come up with an unofficial scale. As in a lot of distributed systems work, there are a lot of factors working together that make a distributed system work. In order to realize the benefits of distributed systems, you need to get through a lot of overhead first, overhead that doesn’t make sense to do if you don’t have a lot of data.

If you’re going even as much as processing up to 10 GB of data at a time, you probably don’t need anything more than a single, powerful server, which can potentially be just the tools that run on your laptop. Or, if you need more leverage, traditional databases like Oracle and Postgres, which is pretty much a miracle database that can even replace an entire ELK stack, run on a single server.

At the very lowest level of data volume, you can work with a program like Excel. Excel is fantastic because it is fast, and allows you to do almost anything you want while allowing point and click functionality. It’s also extremely easy to share (everyone has Excel,) and in addition to processing data, can make charts.

There are definitely reasons not to use Excel, including data errors that lead to serious problems in social science research and the financial industry, which is particularly prone to spreadsheet usage.

But the main problem with large volumes of data is that, around 250,000 rows, Excel starts becoming extremely hard to work with. Its specs say it can accept a million plus rows, but right around the quarter-million row mark, Excel spreadsheets become extremely prone to corruption. (I know from personal, painful experience.)

That’s when you can move to the scientific computing stack: pandas for analysis, cleaning, and processing, Jupyter notebooks for visualization, and command line for crunching. You can get pretty far with all three of these locally. The huge benefit, in addition to being able to manipulate more data, is reproducibility. You can re-run all of your data cleaning changes again and again without having to enter in cells using this “stack.” If you need your data to be structured or joined to other data at this level, you can put it in Postgres or MySQL locally.

The next step up is a powerful server.

Once you are processing data at the scale of a Google or Amazon, you need distributed systems.

For now, let’s see just how far we can get locally.

For this example, I did the classic MapReduce exercise of counting words. WordCount in distributed systems is a standard exercise, simply because it really showcases what distributed systems are good at. And, it shows a common business analysis case, particularly in business with lots of web logs: grouping and counting instances of things.

For this example, I decided to use Les Miserables, my favorite musical, and coincidentally, one of the top five longest books in the English language. (Also, if you haven’t seen this Polish mall rendition of “One Day More”, you are missing something special.)

Les Miserables is 655,000 words long, which turns into a 3.2 MB textfile. So, probably you could process one instance of Les Miserables completely in Excel.

All of the code for the talk is here.

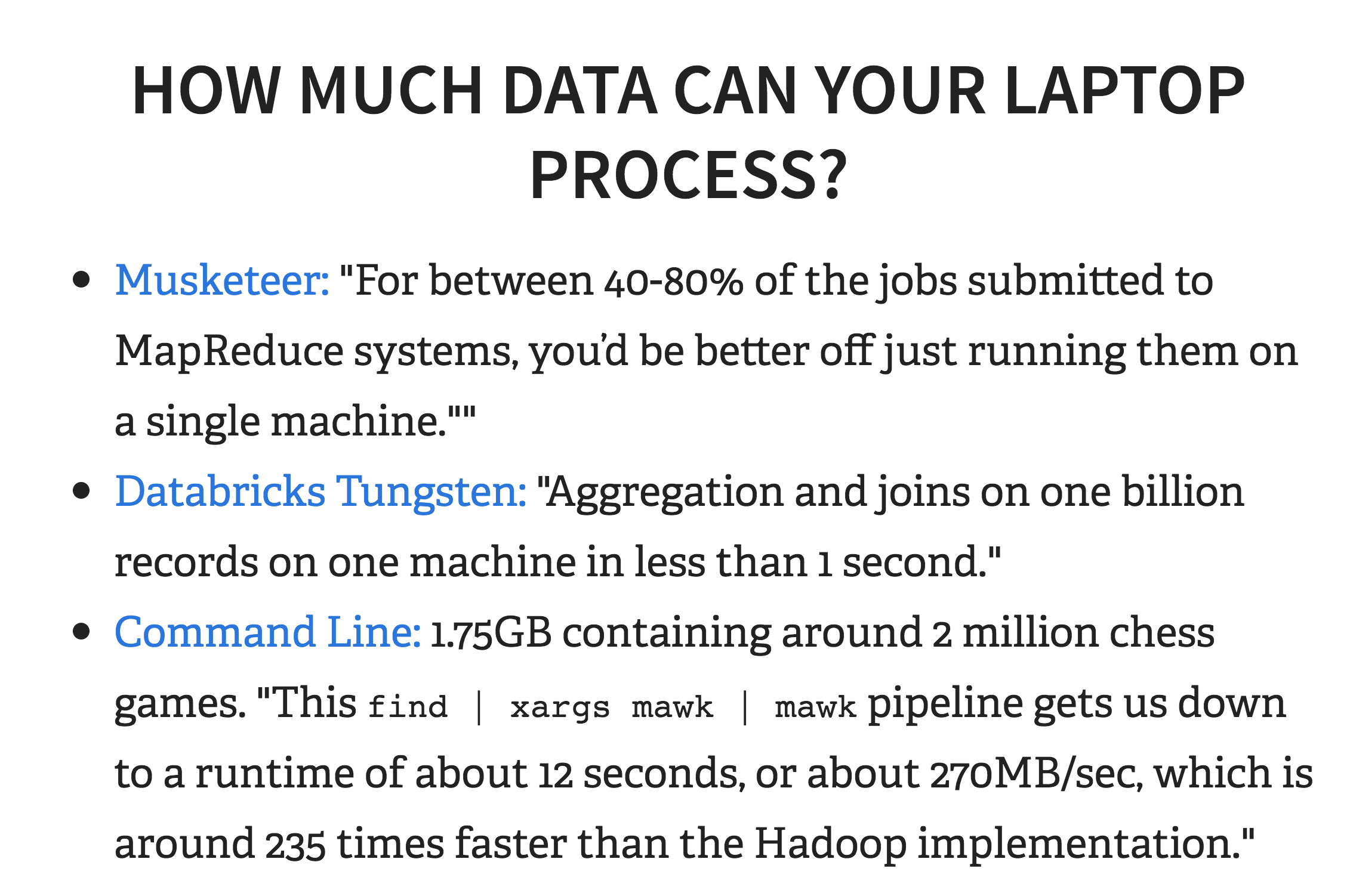

How much data can your laptop process in theory? Databricks, who was founded by the creator of Spark, released Tungsten, an execution engine for Spark, that theoretically can “take less than one second to perform the hash join operation on 1 billion tuples on both the Databricks platform (with Intel Haswell processor 3 cores) as well as on a 2013 Macbook Pro (with mobile Intel Haswell i7).”

There was also recently an experiment where the author processed “1.75GB containing around 2 million chess games” in 12 seconds by parallelizing Linux shell commands with xargs and mawk.

Given the right toolset and a bit of tweaking, you can often save a bunch of time of going to distributed systems by doing it locally.

Let’s take a look at our file, a standard text file.

vboykis$ head -n 1000 lesmiserables.txt

On the other hand, this affair afforded great delight to Madame Magloire.

"Good," said she to Mademoiselle Baptistine;

"Monseigneur began with other people,

but he has had to wind up with himself, after all.

He has regulated all his charities.

Now here are three thousand francs for us! At last!"

Let’s say we want to count the words in Les Miserables to see which character is the most prominent. If we have Linux/Mac, we can use command line tools to write a pipeline to process the data. The following command line pipe does a bunch of ETL tasks in the first couple lines (i.e. strips the words, converts them all to lower case, and puts each word on its own separate line.) It then does the meat of the map-reduce pattern here:

uniq -c, and outputs the text below.

sed -e 's/[^[:alpha:]]/ /g' lesmiserables.txt \ # only alpha

| tr '\n' " " \ # replace lines with spaces

| tr -s " " \ # compresses adjacent spaces

| tr " " '\n' \ # spaces to linebreaks

| tr 'A-Z' 'a-z' \ # removes uppercase

| sort \ # sorts words alphabetically

| uniq -c \ # counts unique occurrences

| sort -nr \ # sorts in numeric order reverse

| nl \ # line numbers

46 1374 marius

47 1366 when

48 1316 we

49 1252 their

50 1238 jean

It takes seconds.

That’s cool. But what if you have a LOT of these files? Like, say, 2000? (Which is around 6 GB of data.)

# Makes n number of copies of Les Miserables

INPUT=lesmiserables.txt

for num in $(seq 1 2000)

do

bn=$(basename $INPUT .txt)

cp $INPUT $bn$num.txt

done

Then you can optimize parallelization by invoking mawk and args.

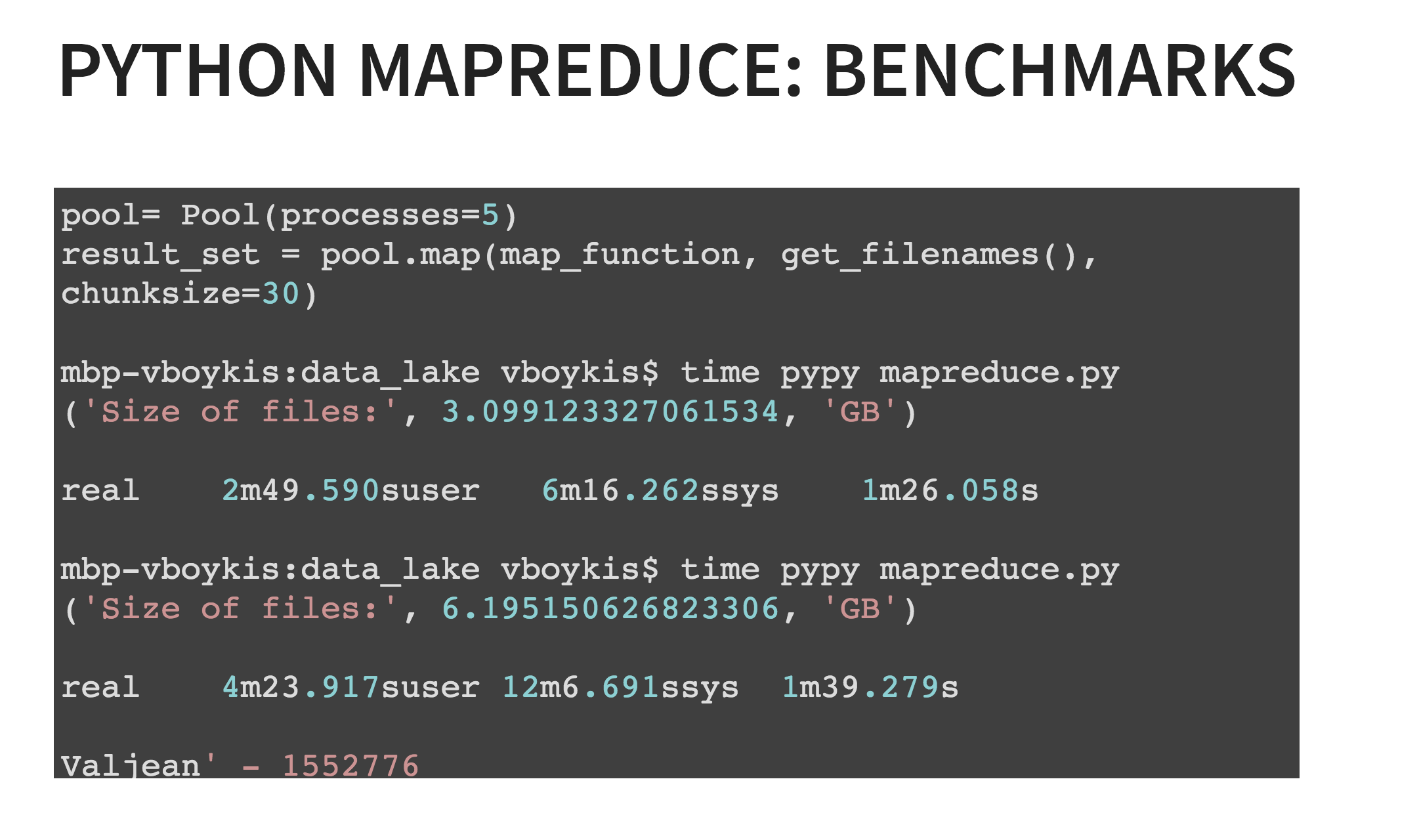

Or, you can move to Python by writing some Python code that MapReduces stuff. The heart of the code is the map_function, which looks at each single word in the text and adds them to a Python dictionary if it isn’t there already. (You could also use defaultdict.)

The other key part is the Pool object, which is part of the multiprocessing library in Python, which allows you to create parallelized Python tasks. Running both that optimization, and running programs with PyPy, means that you can process 6 GB of Les Miserables data in 4 minutes max on your local machine. (Of course, YMMV depending on settings, RAM, etc.)

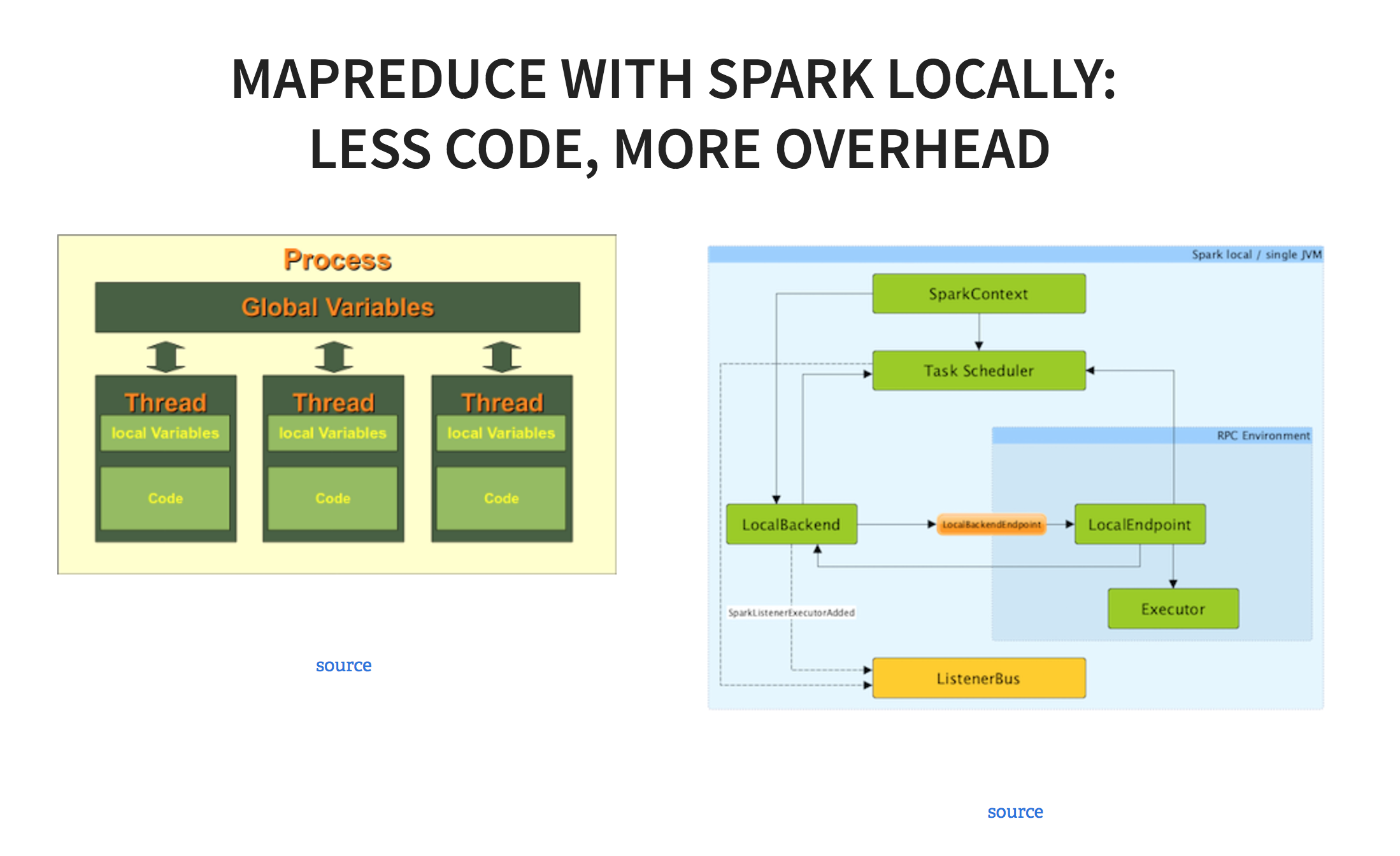

If you don’t feel like writing a ton of Python, that’s cool. You can also write a much shorter Spark job. You can run Spark locally and simulate multiple cores by setting the master to local and telling it how many threads you want to run.

vboykis$ time ./bin/spark-submit --master local[5]/ spark_wordcount.py

sc = SparkContext("local", "Les Mis Word Count")

logFile = "/lesmiserables*.txt"

wordcounts = sc.textFile(logFile).map( lambda x:

x.replace(',',' ') \

.replace('.',' ') \

.replace('-',' ')\

.lower()) \

.flatMap(lambda x: x.split()) \

.map(lambda x: (x, 1)) \

.reduceByKey(lambda x,y:x+y) \

.map(lambda x:(x[1],x[0])) \

.sortByKey(False)

print(wordcounts.take(10)) #print first 10 results

sc.stop()

The upside is that this code is much, much faster to write. The downside is, that, since Spark is optimized for distributed systems, it spawns up a bunch of processes that listen to various parts of the architecture. The essence of Spark is the driver program that manages a number of different worker threads(in this case, 5) As a result, it takes a long time to run - 26 minutes for this particular job.

So there are a number of ways you can do raw data processing on your laptop, of at least 6 GB at a time. The next question is whether you want to process this much data to begin with. In some cases, particularly if you’re dealing with a ton of homogenous log data, it might make sense to take samples. The government does a lot of sampling., as do polls. Random sampling can be a very effective way to get the data you need, if your sample is large enough. If you have a total of 50 customers and sample 25, and all 25 are in California whereas your population is nationwide, it won’t work, and the sample will be extremely biased and will give you an incorrect answer.

However, in a lot of cases, gathering more data comes at an expense: more data is more accurate, but it also takes more time to process. You have to decide whether the extra time to set up an entire architecture to ingest all of your data is worth the extra decrease in margin of error, which tells us the difference between the sample and the population if the data is unbiased. The larger the sample size is, the more you’ll notice the margin of error decreases and the sample gets closer to the population, but the growth is exponential, so it slows down.

Here’s a script to calculate the correct sample size. You can run it and play around for yourself to see that even extremely large sample sizes don’t offer that much of an increase in accuracy.

So far, I’ve talked a lot about small, undistributed, relational systems. If you’re thinking about moving to big data, it’s important to understand what those systems can give you over distributed systems like Hadoop or Cassandra.

Those systems can’t give you data integrity or normalized naming conventions. I like to offer the analogy of traditional databases as shelves of books in a library: the books are organized in a specific order. It may take a very long time to put all the books away because you have to look up where each one goes alphabetically on a shelf, go to that shelf, and put the book in the right place, then repeat all over again. But, it’s very easy to look something up. This is the main concept behind schema-on-write: you predefine how you want your data to be organized, and then you organize it. Distributed data systems, like Hadoop’s HDFS, on the other hand, operate on a schema-on-read paradigm, which means all of your data is unorganized until the very minute you need it, which is when you create it on the fly. I liken it to ripping all the pages out of the books, and putting them in a pile on the floor. It’s very easy to move this pile, but very hard to find what you want in it unless you specify a structure, like sorting pages by book name, or page number, or the like.

As a result of this paradigm, it’s very hard to perform traditional SQL-like analyses on distributed systems unless the structures are created on top of the data in HDFS, which means analysts can lose time as they wait for engineers to pre-define Hive tables. You’re also losing out on consistency in a tradeoff for eventual consistency, which means it’s very important to understand that distributed systems are not like traditional file systems on your computer (like the one processing the Les Miserables data,) and not like traditional databases, either: you can’t keep track of transactions in the same way.

And, as I’ve been mentioning all along, there is a lot of overhead with the amount of components a distributed system requires to work correctly. By the time you start up Hadoop, you might have already run your “command line job,” and in fact, a recent paper found that almost every distributed system is configured in an unoptimal way such as to incur “COSTS” as compared to single-threaded systems.

There are also tons of benefits of distributed systems, which is why many companies are using them. First, they allow for much better storage of unstructured data, which relational systems and traditional file systems do not. These can include things like call center recordings, video, images, and XML blobs, which don’t play well with relational systems at all. They also provide for more reliability in that if one node goes down, the Name Node or manager redirects to the replicate copies of the data. This is how AWS (until recently), and Netflix remain up 99% of the time. Here’s a good comic about how data replication works in Hadoop. And, because the systems are architected in such a way to handle a lot of concurrent traffic, they’re great if you have lots and lots of concurrent users.

A big business case for distributed systems is the shared aspect. Oftentimes, businesses have siloed data that can’t mesh well together and will start the case for a data lake, which can bring in lots of different kinds of data.

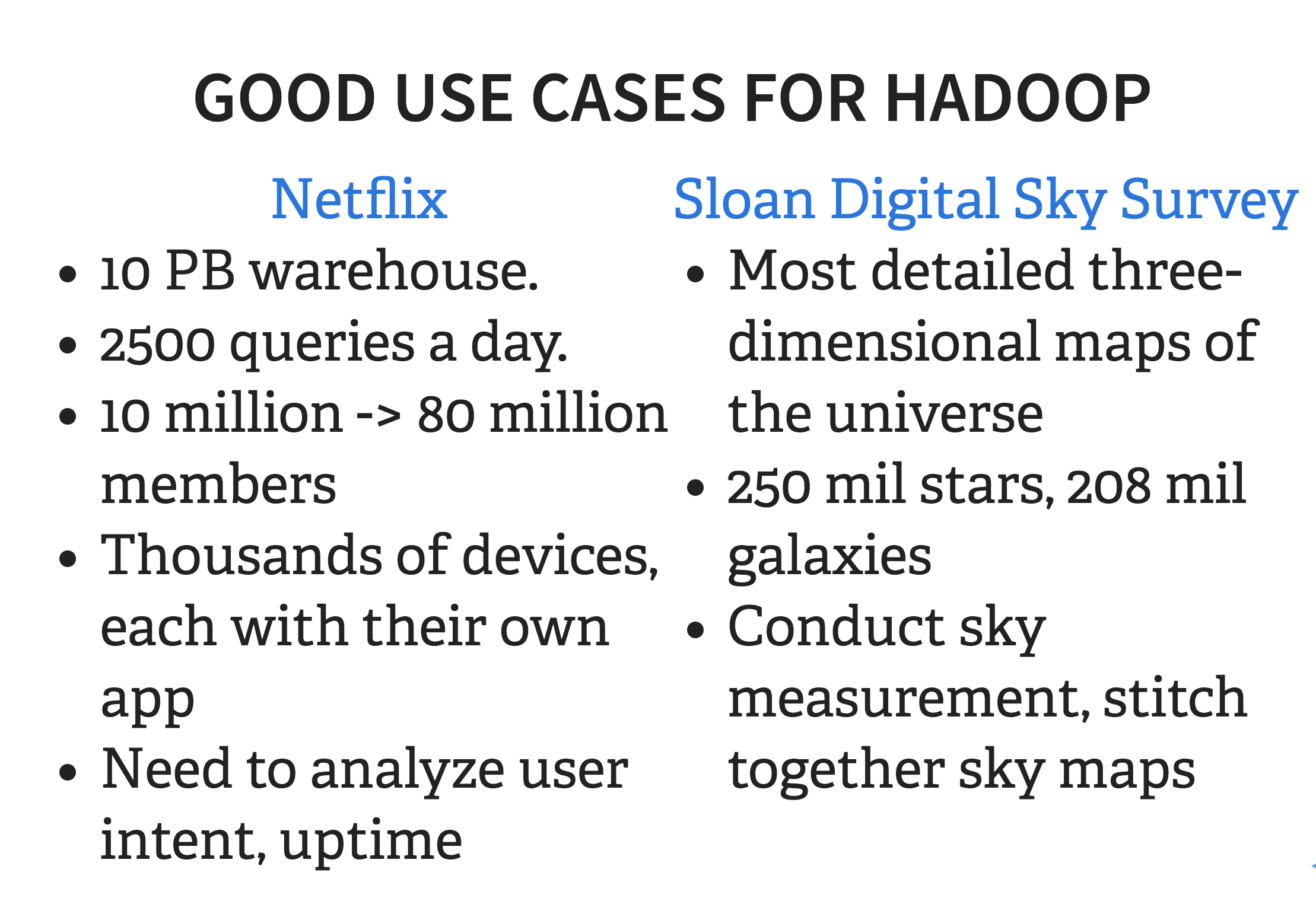

Some really good examples of cases where Hadoop makes sense are Netflix in the commercial space, and Sloan Digital Sky Survey in the academic space. These are both cases where there are hundreds, maybe even thousands of users, querying and transforming datasets that are terabytes to petabytes in size, and growing. Netflix needs to have 99% uptime reliability so it can provide streaming video constantly, and the digital sky survey needs to be accessible to lots of scientists looking for the most accurate star maps for publication-quality data.

With great power, comes great responsibility. Distributed systems are complicated! If you do decide to go the Hadoop route, there are a number of things that need to be configured to make the system work correctly. First, there is a lot of admin overhead. You need to have one to two people who really know what they’re doing and understand all the layers where things can go wrong: Linux Filesystem, Hadoop, Networking, Application Layer (Spark, Hive, etc.) There’s also an entire authentication/authorization/security component that’s important to understand, as well. And, as with any complex system, you’ll need a lot of people to manage it: one architect, two developers, and one or two analysts, at a very minimum.

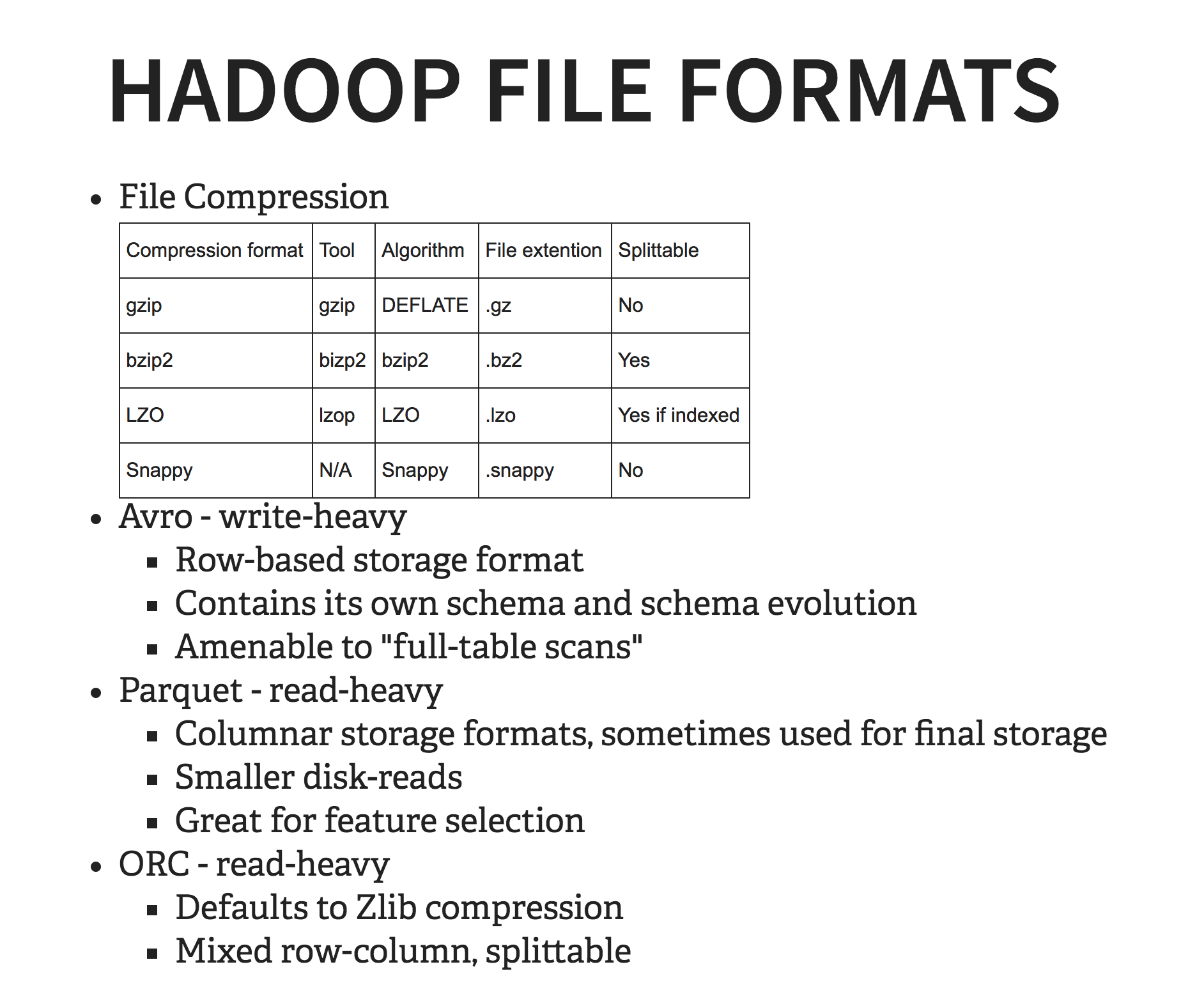

There are also a couple of internal things you’ll need to be very familiar with: Hadoop file formats, and optimal languages for Hadoop.

There are a LOT of Hadoop file formats. The most common ones are Parquet, Avro, and ORC. Each of them has their pluses and minuses,and each is suited for different use case, which will depend on how, ultimately, the data is being used, which goes back to that schema-on-read concept I mentioned earlier. Each also works better with a different compression format, which is fun. Here’s a great site that does a fantastic job giving an overview. The main thing to remember here is that you want to conduct tests on the actual sample data that you’ll be using.

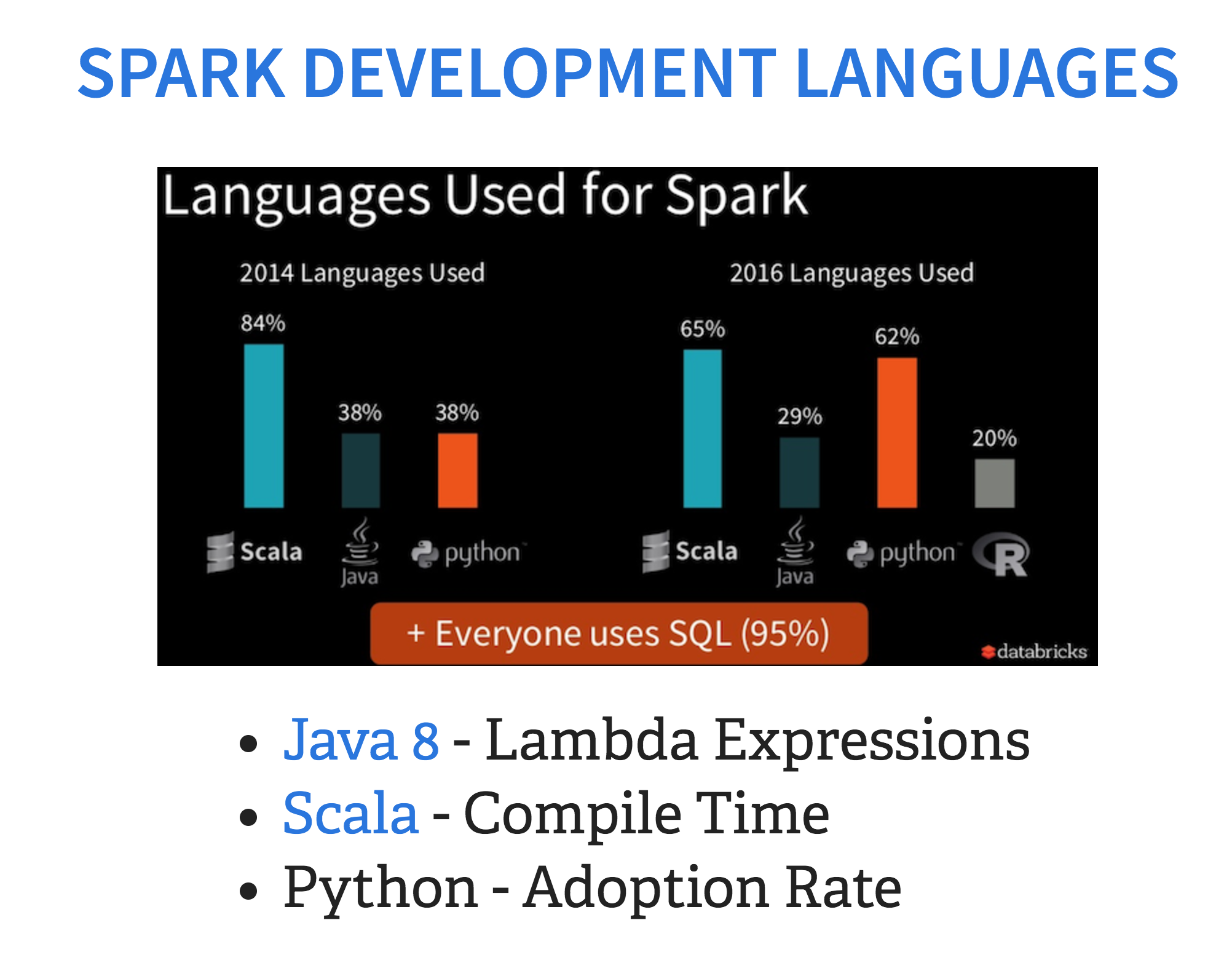

There is also a huge debate about which programming language is best suited to Hadoop development, particularly now that Spark is going to play a much more important role in the Hadoop ecosystem. Particularly for Spark, there is a huge debate about whether to use Scala or Python with regards to speed. It depends. If you’re developing ETL applications, the answer is usually Scala. Although, with lambda expressions coming to Java 8. If you’re already a Java developer, it may be faster for you to get started that way. If you’re doing machine learning, Python will probably be more familiar and more flexible. There is some debate about Python being slower than Scala, particularly since Spark is written in Scala, but you have to factor in the time to learn the development language as well as compile time.

That’s the end of the talk, but only the beginning of your journey in distributed systems. If you only take one thing away, is that every design choice comes with a tradeoff, some of which might initially be invisible to the naked eye. Hopefully this gives you a good place to start.

Good luck :)

Icons: made by Freepik from Flaticon are licensed by Creative Commons BY CC 3.0