The Case of the Broken Lambda

Vincent van Gogh, Still Life with Drawing Board, Pipe, Onions and Sealing-Wax (1889)

Table of Contents

- Holmes takes on a new case

- The Case of the Broken Lambda

- Holmes is on it

- How the error was fixed

- Conclusion

Holmes takes on a new case

Holmes and Watson were in Holmes’s study. It was a grey, damp winter evening in London, but the fire was burning merrily, and tea was on. For a time, they sat in contented silence together. Then, Holmes reached lazily for his pipe.

“Watson,” he said, taking a pinch of tobacco and gently tapping it into place. “Did I ever tell you about the peculiar case of heinous crimes against Python in the cloud that I encountered recently?”

“No, my dear Holmes, what was it?”

“The Case of the Broken Lambda,” Holmes said evenly, staring into the flickering flames. Watson felt a chill race down his spine, and reached for a poker to stoke the fire. He motioned for Holmes to continue.

“Well, it was back in ‘18 that a Datum Minder called me into her laboratory. When she opened the door, her hair was askance. She looked like she had not slept for several days, and her cabinet was littered with empty coffee cups and Dove chocolate bar wrappers with inspirational sayings on the inside. Soundcloud laid down a soft, thrumming beat in the background. She was at quite a low point.”

“I said, ‘Madam, how may I be of assistance.’ She just kept repeating frantically was that she needed this Lambda to go to prod at the end of the sprint, but that she just couldn’t get it to work. "

“I assured her that I was here to help her with all her engineering needs. After all, as I once said, when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be a Python packaging issue, and whatever the issue is, we’ll get to the bottom of it.”

Once she calmed down, she was able to explain her situation.

The Case of the Broken Lambda

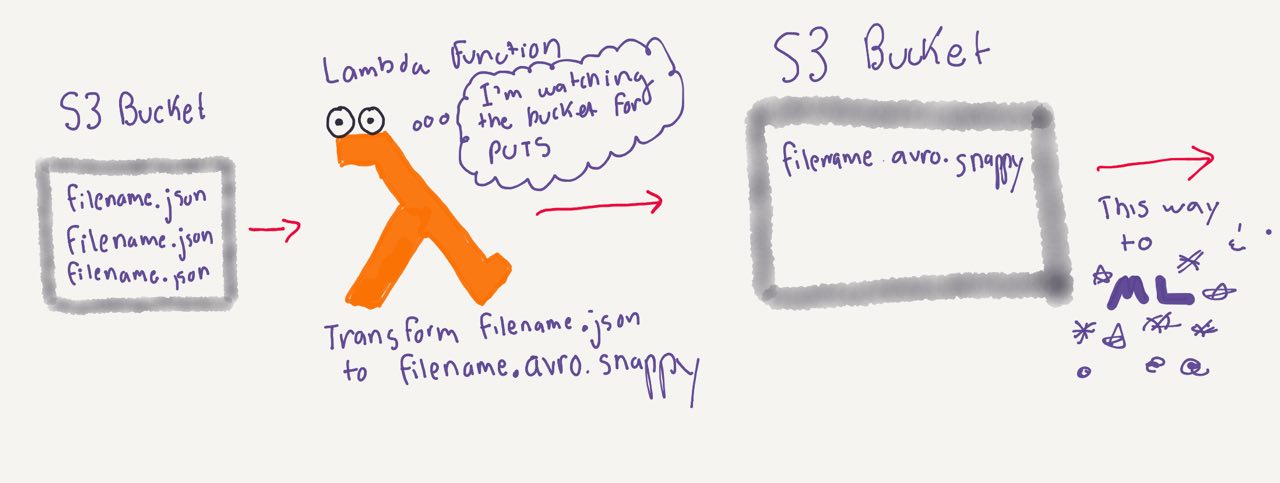

The case was this. At a high level, I’d been ingesting gigabytes of data per day in AWS. Eventually, I wanted to use that data to build machine learning models in Spark and TensorFlow. The data, however, was not in the format I needed. It was coming in as Snappy-compressed JSON files.

I, instead needed the data in Snappy-compressed Avro files.

The reason for this particular workflow is that compressed, serialzed data is cheaper to store and much faster to process downstream in almost all cases.

I needed these snappy-compressed Avro files to be available downstream for simple ad-hoc analysis in Athena, and then, further on down the workflow, in machine learning jobs through Spark on EMR, and Tensorflow on EC2.

Having the data partitioned by year-month-day through S3 prefixes (like so: outpath/year={year}/month={month}/day={day}/hour={hour}) means that data would then easier to query in partitioned Athena tables.

So, I was looking to write a simple AWS Lambda function in Python. The function would listen on an S3 bucket for incoming JSON files, take each file, introspect it, and convert it on the fly to a Snappy-compressed Avro file. It would then put that Avro file into a different, “cleaned” S3 bucket, based on the timestamp in the file.

The detailed workflow looked like this:

Input S3 Bucket triggers an S3 PUT event

Lambda listening to the bucket picks up the event as a JSON notification and:

- Parses out the filename

- Decompresses the JSON-snappy object

- Opens the JSON file object to get the timestamp for year/month/day of the event to later use in the output directory

- Creates an Avro writer file that converts the file to Avro using the

schema_writerand Avro schema associated with the data (for more on Avro conversion, read here) - Converts the file to Avro and compresses with the snappy codec.

Build the Lambda deployment package

Move package to AWS and test against an S3 PUT event

The idea for the Lambda was relatively simple. But, as is often the case with AWS, nothing ever is.

Getting S3 Input Events

S3 buckets generate PUT event notifications whenever files are added to the bucket. These events can be configured as Lambda triggers.

Events look like this (Here’s a sample event I pulled from Lambda’s library of sample event types, which you can see in the Lambda UI:

{

"Records": [

{

"eventVersion": "2.0",

"eventTime": "1970-01-01T00:00:00.000Z",

"requestParameters": {

"sourceIPAddress": "127.0.0.1"

},

"s3": {

"configurationId": "testConfigRule",

"object": {

"eTag": "0123456789abcdef0123456789abcdef",

"sequencer": "0A1B2C3D4E5F678901",

"key": "filename.json",

"size": 1024

},

"bucket": {

"arn": "arn:aws:s3:::mybucket",

"name": "sourcebucket",

"ownerIdentity": {

"principalId": "EXAMPLE"

}

},

"s3SchemaVersion": "1.0"

},

"responseElements": {

"x-amz-id-2": "EXAMPLE123/5678abcdefghijklambdaisawesome/mnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGH",

"x-amz-request-id": "EXAMPLE123456789"

},

"awsRegion": "us-east-1",

"eventName": "ObjectCreated:Put",

"userIdentity": {

"principalId": "EXAMPLE"

},

"eventSource": "aws:s3"

}

]

}

The Lambda would see one of these ObjectCreated:Put events come in and use it as input into the lambda handler event parameter. The parameter, once passed into the Lambda, would convert filename.json within the Lambda function’s temp space into an Avro file.

Writing the Lambda

The code below does all of that, in sequence.

It first imports all the Python libraries. Then, it sets up the lambda handler with

def lambda_handler(event, context):

It loops through each record present in the file with

for record in event['Records']:

Initially it decompresses the file with snappy:

uncompressed = snappy.uncompress(file_body).decode("utf-8")

and eventually writes to an Avro file with snappy compression. It moves that file out of the Lambda temp space and into a new file in a new bucket.

writer = datafile.DataFileWriter(open(tmp_file_location, "wb"), io.DatumWriter(), schema_writer,codec="snappy") writer.append(json_string)

It’s easy to see why Python Lambdas are such a popular all-purpose tool in the AWS ecosystem. There’s minimal boilerplate, and the code is extremely legible.

# Package modules

import logging

import json

import urllib

from pathlib import Path

# Boto and OS

import boto3

import os

import tempfile

import datetime

# Snappy Decompression

import snappy

# Avro

from avro import io

from avro import schema

from avro import datafile

logger = logging.getLogger()

logger.setLevel(logging.INFO)

def lambda_handler(event, context):

# connect to S3

s3 = boto3.resource('s3', region_name='us-east-1')

# Production Connection

# s3 = boto3.resource('s3', region_name=os.environ['REGION_NAME'])

# Create an Avro data writer

schema_writer = schema.Parse(open("../lib/schema.avsc", "rb").read())

for record in event['Records']:

# use the S3 event put as a trigger

bucket = record['s3']['bucket']['name']

ingest_key = record['s3']['object']['key']

# create Avro file within lambda tmp directory

tmp_dir = tempfile.gettempdir()

# get filename without .snappy and .json extensions

filename = Path(Path(ingest_key).stem).stem

#set tmp filename to filename sans extensions

outfile_name = f"{filename}.avro.snappy"

tmp_file_location = f"{tmp_dir}/{outfile_name}"

# parse URL twice

key = urllib.parse.unquote(urllib.parse.unquote(ingest_key))

obj = s3.Object(bucket, key)

file_body = obj.get()['Body'].read()

uncompressed = snappy.uncompress(file_body).decode("utf-8")

json_string = json.loads(uncompressed)

timestamp = json_string['PTS']

if timestamp is not None:

datetime_ts = datetime.datetime.fromtimestamp(int(timestamp) / 1e3)

year = datetime_ts.strftime('%Y')

month = datetime_ts.strftime('%m')

day = datetime_ts.strftime('%d')

hour = datetime_ts.strftime('%H')

file_path = f"outpath/year={year}/month={month}/day={day}/hour={hour}"

writer = datafile.DataFileWriter(open(tmp_file_location, "wb"), \

io.DatumWriter(), \

schema_writer, \

codec="snappy")

writer.append(json_string)

writer.close()

# Move Avro file to correct folder

s3.Bucket(bucket).upload_file(tmp_file_location, file_path)

The next step was to zip up the Lambda executable and its dependencies to the Lambda console and test an execution against the test event above.

I should note that there are lots and lots of different ways to test Lambdas. My favorite one is this one, but sometimes going to the AWS console can be the path of least resistance.

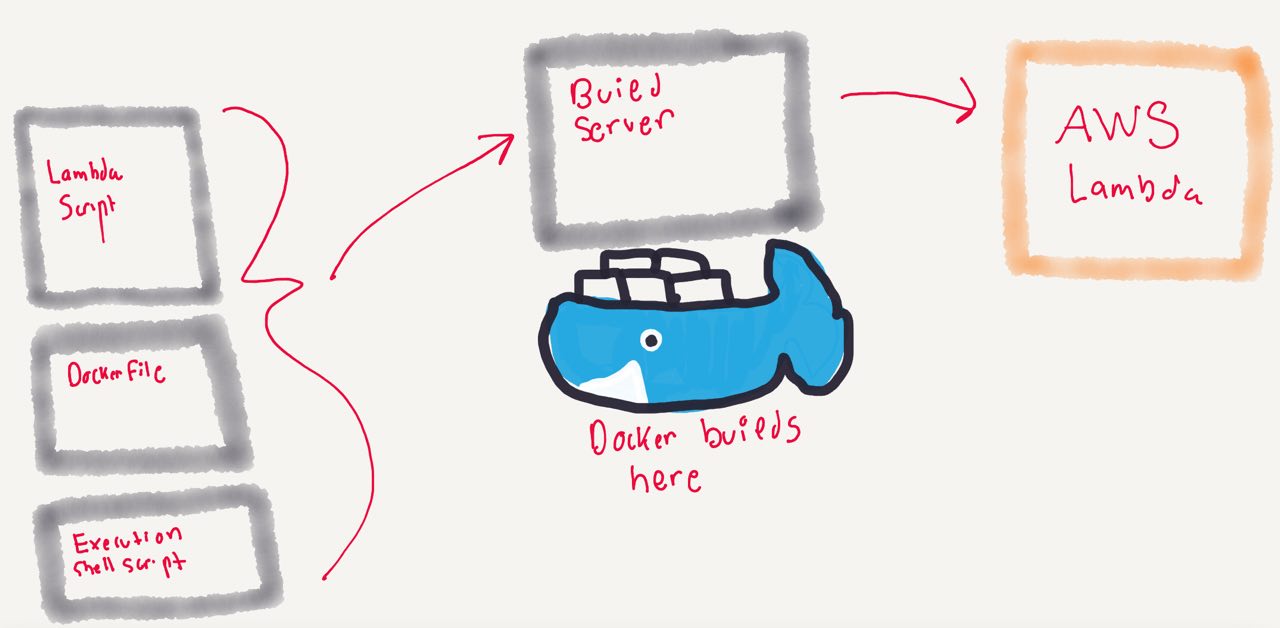

Building the Lambda Package

First, I created a virtual environment through Pipenv and zipped everything into the venv. I also included the Avro schema in the final zip file.

All of this ran through a CI flow that was kicked off when I pushed to the master branch of my GitHub repo.

The process looked like this:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

echo "Start script"

# Moving to top level of project dir

cd /usr/lambda

DIR=$(pwd)

echo "${DIR}/"

# Cleaning up the distribution directory

echo "Cleaning up/creating dist dir ..."

mkdir -p "${DIR}/dist"

# Create correct pipenv virtual environment

pipenv install

VENV_DIR=`pipenv --venv`

PYTHON_VERSION="3.6"

SITE_PACKAGES_DIR="${VENV_DIR}/lib/python${PYTHON_VERSION}/site-packages"

# zipping lambda into the zip file

cd "${DIR}"

echo "${DIR}"

zip -r -q --exclude="*.json" --exclude="*.git*" --exclude="*.pytest_cache*" "${DIR}/dist/lambda=.zip" .

# zipping dependencies into the zip file

cd "${SITE_PACKAGES_DIR}"

zip -r -q --exclude="*.git*" --exclude="*.idea*" --exclude="*.pytest_cache*" "${DIR}/dist/lambda.zip" .

# zipping schema into the zipfile

cd "${DIR}/lib"

zip -r -q --exclude="*.git*" --exclude="*.idea*" --exclude="*.pytest_cache*" "${DIR}/dist/lambda.zip" .

echo "Lambda package built"

For reference, my folder structure was:

lambda

├── Dockerfile

├── Jenkinsfile

├── Pipfile

├── Pipfile.lock

├── README.md

├── init.py

├── bin

build_lambda.sh

├── dist

lambda_function.zip

├── lambda

lambda_function.py

├── lib

└── tests

The Error

But, when I tried to trigger a test of the Lambda using the test JSON event as an input, the console gave me the following error:

"Traceback (most recent call last):

from _snappy import UncompressError, compress, decompress, \

ImportError: libsnappy.so.1: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory"

What was going on here?

The most important indicator was the exception type: ImportError.

This meant that something was weird in an imported Python module. Taking a look at the import statement, the Pipfile, and the error statement, the most likely culprit was the snappy library, used to compress the file at the very end.

What was wrong with Snappy?

Investigating Snappy errors

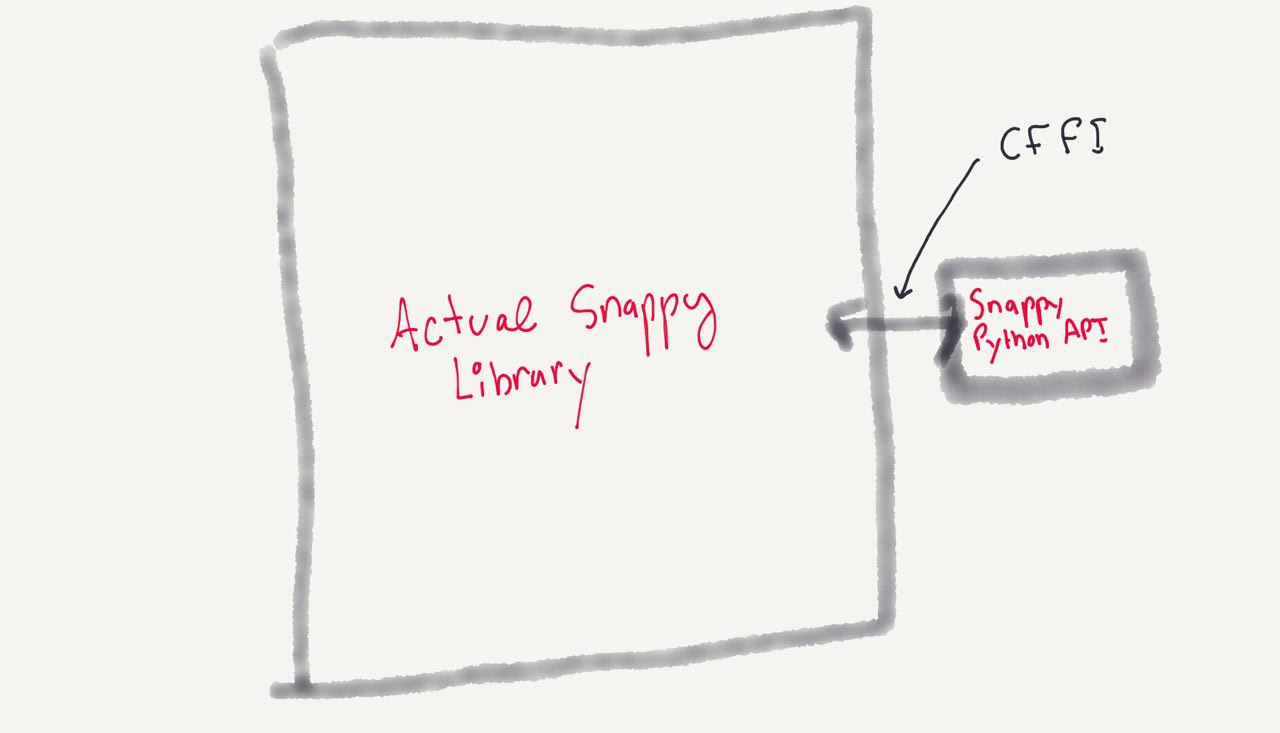

Snappy is a library that compresses and decompresses files. In the case of this package, it decompresses from json/snappy. It was initially build by Google in C., but has bindings to several other languages ., including Python.

The issue with the Python version of the module is that it has C extensions. In this case, Python is a wrapper, or API on top of C, which does most of the actual work of compressing the file.

When Python libraries with C extensions are used in any given environment, they need to be compiled on an environment that exactly matches the host environment, (in this case, the Lambda.) For snappy specifically, it needs to be built as a 64bit x86 Linux-compiled library. The environment the Lambda runs on is the same as the Linux public AMI. and the instructions say,

If you’re using any native binaries in your code, make sure that they’re compiled against the package and library versions from this AMI and kernel.

What wasn’t loading specifically was cffi, the actual C module that allows Python to talk to C.

It turned out that this was seemingly commonly-known issue., and that I should have been looking really at the dependency on cffi.. What this means is that, in theory, every Python package that has C dependencies needs to put everything in a Docker container to build the binary, put the Docker image on a build server, and have the build server send the compiled package to AWS.

The Linux AMI docker image is available on Docker, but Amazon Linux Extras, which makes Python available is still relatively new, so people have had to resort to Dockerfiles lile this one., where Python is installed through wget or curl.

With Python, having to build C dependencies, and AWS Linux’s lack of Python availability (up until recently),there are too many layers where something goes wrong.

By the end of the project, this was where I was: with a broken Lambda that didn’t compile, dozens of shell scripts, and a very long and ungly Dockerfile.

Holmes is on it

“As she finished her story, the Datum Minder turned to me with immensely sad eyes. ‘Surely you must know, Mr. Holmes, of a way around this error? I can’t sleep. I can’t eat. I can’t deploy my Lambda.’ "

“I sat for a long time at her bureau, assembling the facts of the case. I thought about all of the layers of errors that had happened. I thought about the Lambda runtime environment. I thought about Snappy. I thought about the Linux 2 Docker issue. I thought about Python packaging. After a spell, finally I realized that I had gotten in so deep as to lose my sanity.”

“Well, it looks like you have quite a case here,” I said to her with utmost gravity. She looked at me with hope in her eyes.

" ‘And, as I have said, there is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact. And the obvious fact here is that this problem is much better suited to you solving it rather than me mucking about.’ ‘But,’ she began to protest, but I held up a hand for silence. ‘This is why they call you the Datum Minder and pay you the big bucks. Good luck, dear,’ I said, and took my leave.”

How the error was fixed

The fire had gone low, and only glowing embers remained. Watson shivered as he prodded them with the poker. “So what did you do, Holmes? Surely you didn’t leave the poor lass hanging?”

“Oh no, I went quite far away so she couldn’t ask me any more questions about Python packaging in the cloud. Fortunately, she had connected at that point with a European fellow named Gügl who seemed to be getting her to where she needed to go.”

“A month or so later, I decided to call on her and make sure she was still alive. She was, and seemed in much better health. Her complexion was much-improved, she had luster in her eyes, and her Lambda was deployed to production. ‘What did you do,’ I asked. "

“Oh, I ended up rewriting the Lambda in Java, a language that we now have several Lambdas running on. Usually, I wouldn’t recommend Java because it’s a hellscape of types and boilerplate Factories, but in this particular case, it made sense. The everything-in-one nature of the JAR file allowed me to simply include xerial as a dependency in my Maven POM.

“The inclusive nature of the JVM as a package manager and platform allowed me to ship the project without even having to Dockerize it, and we are now happily converting events left and right.”

“Of course, there are downsides. Java is a much harder language to write Lambdas in. I mean, just look at this code to generate the handler and connect to AWS:”

import com.amazonaws.auth.DefaultAWSCredentialsProviderChain;

import com.amazonaws.services.lambda.runtime.Context;

import com.amazonaws.services.lambda.runtime.LambdaLogger;

import com.amazonaws.services.lambda.runtime.RequestHandler;

import com.amazonaws.services.lambda.runtime.events.S3Event;

import com.amazonaws.services.s3.AmazonS3;

import com.amazonaws.services.s3.AmazonS3ClientBuilder;

import com.amazonaws.services.s3.model.GetObjectRequest;

import com.amazonaws.services.s3.model.PutObjectRequest;

import com.amazonaws.services.s3.model.PutObjectResult;

import com.amazonaws.services.s3.model.S3Object;

public class TransformToAvro implements RequestHandler<S3Event, String> {

private static AmazonS3 s3 = AmazonS3ClientBuilder.standard()

.withCredentials(new DefaultAWSCredentialsProviderChain())

.withRegion("us-east-1")

.build();

}

“And the other downside is the warmup time, if that’s important to you - it’s longer for JVM-based projects. "

“The upside, however, is that everything goes together.”

“Of course, as soon as I wrapped up the project, I found a potential work-around, in this lambda-packages library. But, I haven’t tried it yet, and I’m not quite sure how to get started with Zappa or what kind of overhead that involve. Additionally, the library doesn’t build snappy exclusively - only cffi. Which, hypothetically, should solve the problem, but may not.”

“Given my time constraints, what I had to work with, and other Lambdas that we had that were already written in Java, Java ended up being the answer. If I had to do it again, with an unlimited schedule, I’d look into Zappa.”

Conclusion

Holmes and Watson sat in the darkness, the tea gone cold, the pipes put aside. “I don’t know how she did it, Watson,” Holmes said, shaking his head. “But I do know that, after hearing that story, I decided to retire from cloud consulting entirely. It’s far easier to investigate murders than Python package conflicts in the cloud.”