Commit to your lock-in

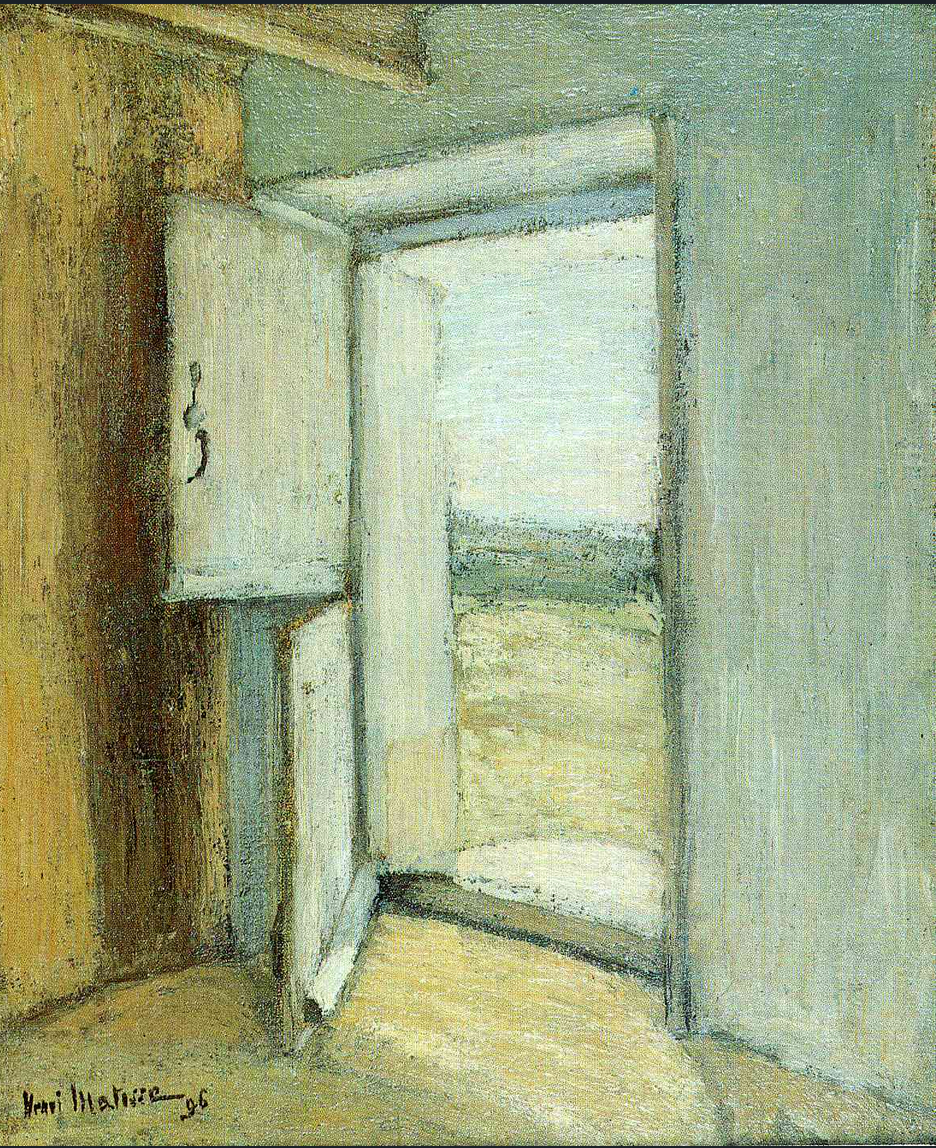

Open Door, Brittany - Henri Matisse, 1896

Open Door, Brittany - Henri Matisse, 1896A rising concern as companies continue moving infrastructure to the cloud is vendor-lock in.

For example, I recently came across a post from 2017 discussing the impact of Lambdas locking you into the AWS ecosystem.

“It’s code that tied not just to hardware – which we’ve seen before – but to a data center, you can’t even get the hardware yourself. And that hardware is now custom fabbed for the cloud providers with dark fiber that runs all around the world, just for them. So literally the application you write will never get the performance or responsiveness or the ability to be ported somewhere else without having the deployment footprint of Amazon.”

It’s true that there is something unnerving about putting all of your trust in a microservic-ey piece of code that runs in a given, custom run-time, with architectures that are hard to reverse-engineer, and take platform-specific triggers (PDF), like S3 calls, as input events.

That’s a fair assessment. But evaluating serverless functionality on its own, without looking at the alternative path, is not entirely fair. Let’s say you’re trying to solve the problem of cleaning up log files (by, for example, anonymizing or hashing customer IDs) that land on a minute-by-minute basis in S3 and puts them in a different S3 bucket (or other, vendor-neutral object storage location).

You can write a Lambda function that processes them and puts them in a different bucket. The vendor-neutral alternatives would be something like:

- Setting up a Spark streaming application to process the files and put them in S3 or another file system.

- Creating a complicated bash script that runs (potentially with the help of a scheduler like Airflow)

- Setting up a Kafka streams application

Each of these is vendor-independent (i.e. can run on an EC2/EMR instance, or in your own data center), but each also offers its own unique set of challenges, and locks you into that architecture moving forward. It’s possible your company won’t want to be on AWS in 2-3 years, and you’ll be stuck trying to figure out how to migrate Lambdas to a different architecture. But it’s also possible for Kafka or Spark features to break, for your Python program to become too inefficient, for Java 11 features to break on Java 12, and so on.

On-prem is a lock-in. Cloud is a lock-in. Every single language you program in is a type of lock-in. Python is easy to get started with, but soon you run into packaging issues and are optimizing the garbage collector. Scala is great, but everyone winds up migrating away from it. And on and on.

Every piece of code written in a given language or framework is a step away from any other language, and five more minutes you’ll have to spend migrating it to something else. That’s fine. You just have to decide what you’re willing to be locked into.

People try to hedge these bets by designing truly platform-agnostic, flexible applications. But, it takes a long time to design a truly generic solution, because humans are terrible at long-term forecasting trends. Who could have predicted that Hadoop only has a lifecycle for 3-4 years? Who could have foreseen the shift from SAS into R? Who foresaw the spiraling growth of the JavaScript community? It’s hard to design resilient applications for needs 6 months into the future, let alone something that will run in five years.

Code these days becomes obsolete so quickly, regardless of what’s chosen. By the time your needs change, by the time the latest framework is obsolete, all of the code will be rotten anyway. Maybe the Postgres database is still going strong, but Node isn’t in favor anymore. AWS and Google Cloud aren’t going anywhere over the next 5-10 years.

The most dangerous feature about these articles examining cloud lock-in is that they introduce a kind of paralysis into teams that result in applications never being completely fleshed out or finished.

In contrast to earlier decades, today we are cursed with an overabundance of technologies that mean that any project starts with a complete evaluation of what makes the most sense. It’s possible to mess up. Even the best senior developers make bad architecture and vendor choices. But the good ones also know that, in order to understand whether something is a bad choice, they need to make the current process work.

It’s possible to spend hours in architecture debates and reading the pros and cons on HN, but what counts most is having something working that you can evaluate. So, write your applications, spin up your Lambdas, keep an ear to the ground, but go to production first.

#cloud #engineering #aws #career advice #software craft