The attic and the basement of apps

Building the Winter Studio. Ekely, Edvard Munch, 1929

My dad can do everything with his hands. From building shelves, to installing sump pumps, to fixing busted Soviet radios from the 1970s, there’s no problem he can’t solve.

Recently, my husband and I undertook what I envisioned as a really small house project: adding three shelves to a hallway closet to better store shoes and coats.

But when we went to the home improvement store, we were completely lost. What kind of shelves did we need? What kind of nails? What would we mount the shelves on? Would they hold the weight of shoes?

My husband can tell you everything you need to know about designing web services that serve millions of concurrent requests per day. I can tell you everything about Python dictionaries.

Neither of us can tell you the anything about nails.

I called my dad.

“We need some help,” I said, and he drove over to the store. He sized up the picture I showed him of the closet. “That won’t work for yours,” he said immediately. “We’re going to need some wood to support the shelves. We’re also going to need to cut the shelves because the dimensions you measured don’t match. Do you have a miter saw?”

Every time I watch my dad undertake a home improvement project, I’m amazed that he immediately knows the way forward in the project. How does he know he needs a saw? How does he know what kind of saw? How does he know what to do to wood?

“How do you know what you know, dad,” I usually ask him, trying to create a mental decision tree for understanding how to pick and assess tools, and his answer is always, “Experience.”

But, I have no framework for understanding the basics of home improvement, so his decisions and questions come across like the incantations of a wizard.

I have the same assessment of Martin Kleppmann after reading his much-lauded “Designing Data-Intensive Applications.”.

Kleppmann very clearly knows absolutely everything there is to know about distributed systems, from soup to nuts. The amount of topics he covers in his book - from - from text encoding, to database data structures, to partitions, - is truly staggering. But I came away disappointed, because what I was really looking for from the book was a set of heuristics that would tell me how to start at the basement of a distributed system and work my way up to understanding how the various components fit and work together. What I wanted was a blueprint for how to build a house, and what I got instead were comprehensive chapters on different power tools.

The author knows everything about distributed systems, but the book doesn’t give a good base for how to think about all of the various parts holistically. For example, the first chapter starts off talking about data-intensive versus compute-intensive applications, and moves immediately into SLOs, SLAs, working with load, and maintainability. The second chapter covers data models, and the third has us building database indexes from scratch using hash indexes and B-trees.

I’ve been working with data for all of my career so far, so the high-level concepts felt intimately familiar. Indices, ACID, network faults, batch and stream processing are things I encounter every day working with large machine learning products.

I work, as most of us do, in the attic of the house of computer science. My level of abstraction is the Kinesis stream, the JSON returned from an API, a Jupyter Notebook running in Sagemaker, an HDFS volume, a compiled JAR, a Tableau chart.

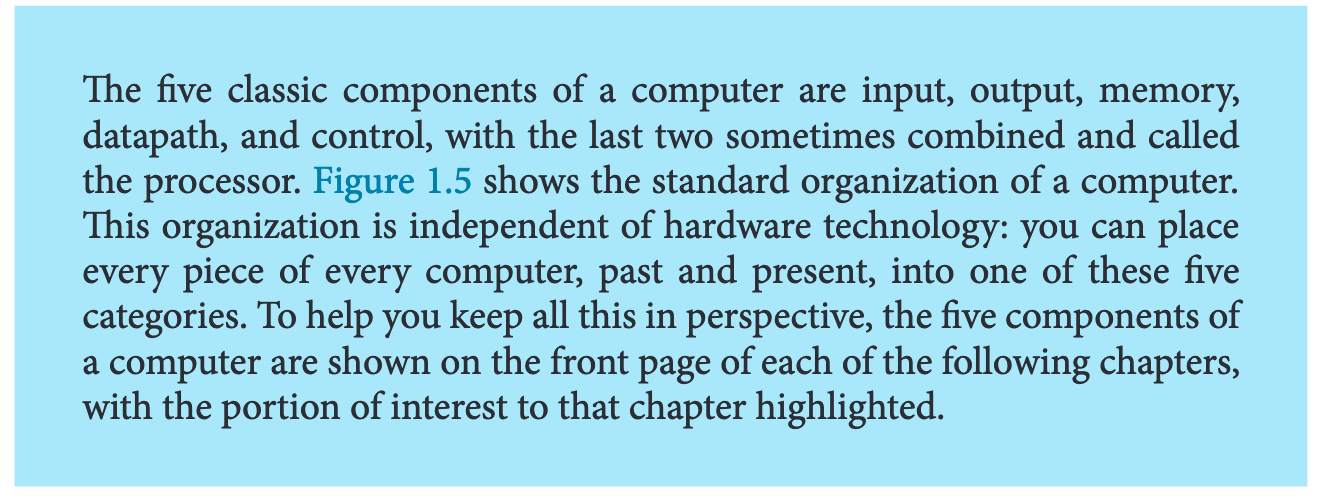

What I really wanted instead of separate chapters on semi-related concepts was something that related and tied all these concepts together. Something along the lines of “Computer Organization and Design” by Patterson and Hennessy, which starts out like this,

This is probably the easiest and most building-block level mental model about how a computer works.

But why are these parts of the computer organized this way? Because computers, at the hardware level, operate using electricity. Electricity transmits signals in ones and zeros (being turned on and off). Computers capture those ones and zeros, and translate them into higher-level abstractions. This is from the wonderful (but also extremely detailed “Code” by Petzold.)

Ones and zeroes operating on circuits are in basement of the house of computers. Theoretically, you can go lower, into figuring out the equations and atoms that power them, but for our purposes, let’s start here.

Those ones and zeros have to go in somewhere, something has to happen to them, and they have to leave somewhere. Or, they have to be stored somewhere.

So, a computer is essentially a machine that takes ones and zeroes and does something with them. What can do things to manipulate that electricity?

Code, which is translated into electronic signals that send instructions to the hardware. That is, software. As Alan Perlis writes in the foreword to Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs,

Unlike programs, computers must obey the laws of physics. If they wish to perform rapidly—a few nanoseconds per state change—they must transmit electrons only small distances (at most 112feet). The heat generated by the huge number of devices so concentrated in space has to be removed. An exquisite engineering art has been developed balancing between multiplicity of function and density of devices. In any event, hardware always operates at a level more primitive than that at which we care to program. The processes that transform our Lisp programs to “machine” programs are themselves abstract models which we program. Their study and creation give a great deal of insight into the or-generational programs associated with programming arbitrary models. Of course, the computer itself can be so modeled. Think of it: the behavior of the smallest physical switching element is modeled by quantum mechanics described by differential equations whose detailed behavior is captured by numerical approximations represented in computer programs executing on computers composed of ..!

We’re now slowly moving up through the basement, to the higher-level elements that are familiar to all developers: CPU, aka datapath and control, the thing that processes our programs, and memory, the piece that stores our programs and data.

Programs and data: now we’re at the two main pieces of things we manipulate in programming (again, from SICP):

In programming, we deal with two kinds of elements: procedures and data. (Later we will discover that they are really not so distinct.) Informally, data is “stuff” that we want to manipulate, and procedures are descriptions of the rules for manipulating the data.

I like to think of procedures as verbs and data as nouns. We can write programs to manipulate the data. The programs will be compiled (or interpreted) down into ones and zeros, the bitcode, and act on the electricity.

There are many, many other moving parts, and, unfortunately, there is no single one place that will teach you these things or how all the moving parts work together. As Paul Ford wrote in his opus “What is code,”

And yet, after two decades of jamming information into my code-resistant brain, I’ve amassed enough knowledge that the computer has revealed itself.

Once you understand enough about these basics, you can move on to the first part of Kleppmann’s book, where he starts by covering databases, queues, and caches.

All of these are types of storage. The first questions asked in the book are about ensuring that data remains complete. But the first question for application developers really should be, why do I need a database, queue, or cache?

Because, based on our five parts of computer above, the input and output are bound by how fast we can send things from input to output. It’s also bound by where the processing is occurring: Are we pulling it from temporary storage (RAM), or from “cold” storage, aka disk? RAM and disk are two extremely important parts of understanding how (eventually) distributed systems work. Caches are good if you need things quickly. Queues are good if you need to process lots of things quickly. Databases are good if you need to read things quickly.

These are the heuristics the book should cover from the get-go, given its stated target audience of “software engineers, software architects, and technical managers who love to code. [The book] is especially relevant if you need to make decisions about the architecture of the systems you work on.”

We are at such a high level of abstraction from the ones and zeroes, and the input and output of the source that we work with sometimes, reasoning in entire distributed systems instead of computers, that it can be hard to understand what the impact of any one given decision is. We are standing on the roof and dropping marbles through the chimney, trying to understand where in the house they end up and what they fall onto.

It’s hard to stop and think about these basic, low-level things. Every day, we deal with extremely high-level abstractions: Postgres, which has data structures (like B-trees and hash maps), which translate into much simpler data structures, which are kept in memory by the C language, which is translated down into assembler, which is then translated into ones and zeros as input and output into the system. AWS Lambda functions, which are pieces of code written in Python on ephemeral servers, which are also just computers managed in the cloud, which is a group of computers, which talk to each other in input and output and store those functions in memory over a larger group of machines. And many, many more.

We, as people who get computers to do things every day, deal with packaging, figuring out different streaming configurations, cloud networking, statistics, and much, much more. We need context and framing around all of these things and how they work in harmony.

Unfortunately, I think we as specialists are not great at writing these kinds of books, simply because we are too far removed from the beginning, and also because it can be hard to hold so many abstractions in memory.

For example, when I was just starting out in programming, every Python tutorial I’d see would go something like this:

Introduction to Python:

Part 1, Data Types: Python has several important data types - integers, floating-point numbers, strings, lists, sets, and dictionaries.

I always wondered why programming languages started out this way. What are data types? Why are they important?

The answer is, data types are important because they take up memory, one of the basic parts of the computer, and because they can lead to slower and faster implementations depending on your choices.

I didn’t get that until I learned about in-memory data structures, memory management, program speed, and much, much more.

What I was looking for from Data-Intensive Applications was a break from the noise and a start from the ground up. I was looking for someone to take me from the basement, to the attic, carefully pointing out all the floors in between.

Because I think the problem is that, as developers, particularly developers today working with hundreds of different stacks and tools, we all are working our way through half-built houses, coming upon a hammer here, a nail there, and building our mental models of how computers, programming, and ecosystems of networks work, brick by brick and board by board, without a blueprint.

It just would be nice if there were an instruction manual laying around somewhere that took us at least through the missing steps, past the plastered walls, to the first floor.

I don’t think Designing Data-Intensive Applications is that book for me, but it did get me to think about this and write this post, so maybe it’s as good of a place as any to start.