A deep dive on Python type hints

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- How Computers Build Our Code

- An introduction to type systems

- Data types in statically versus dynamically typed languages

- Python’s type hints

- Type hints in IDEs

- Getting started with type hints

- So, what’s the verdict? To use or not to use?

Introduction

Since the release of Python’s type hints in 2014, people have been working on adopting them into their codebase. We’re now at a point where I’d gamely estimate that about 20-30% of Python 3 codebases are using hints (also sometimes called annotations). Over the past year, I’ve been seeing them pop up in more and more books and tutorials.

Actually, now I'm curious - if you actively develop in Python 3, are you using type annotations/hints in your code?

— Vicki Boykis (@vboykis) May 14, 2019

Here’s the canonical example of what code looks like with type hints.

Code before type hints:

def greeting(name):

return 'Hello ' + name

Code after hints:

def greeting(name: str) -> str:

return 'Hello ' + name

The boilerplate format for hints is typically:

def function(variable: input_type) -> return_type:

pass

However, there’s still a lot of confusion around what they are (and what they’re even called - are they hints or annotations? For the sake of this article, I’ll call them hints), and how they can benefit your code base.

When I started to investigate and weigh whether type hints made sense for me to use, I became super confused. So, like I usually do with things I don’t understand, I decided to dig in further, and am hopeful that this post will be just as helpful for others.

As usual, if you see something and want to comment, feel free to submit a pull request.

How Computers Build Our Code

To understand what the Python core developers are trying to do here with type hints, let’s go down a couple levels from Python, and get a better understanding of how computers and programming languages work in general.

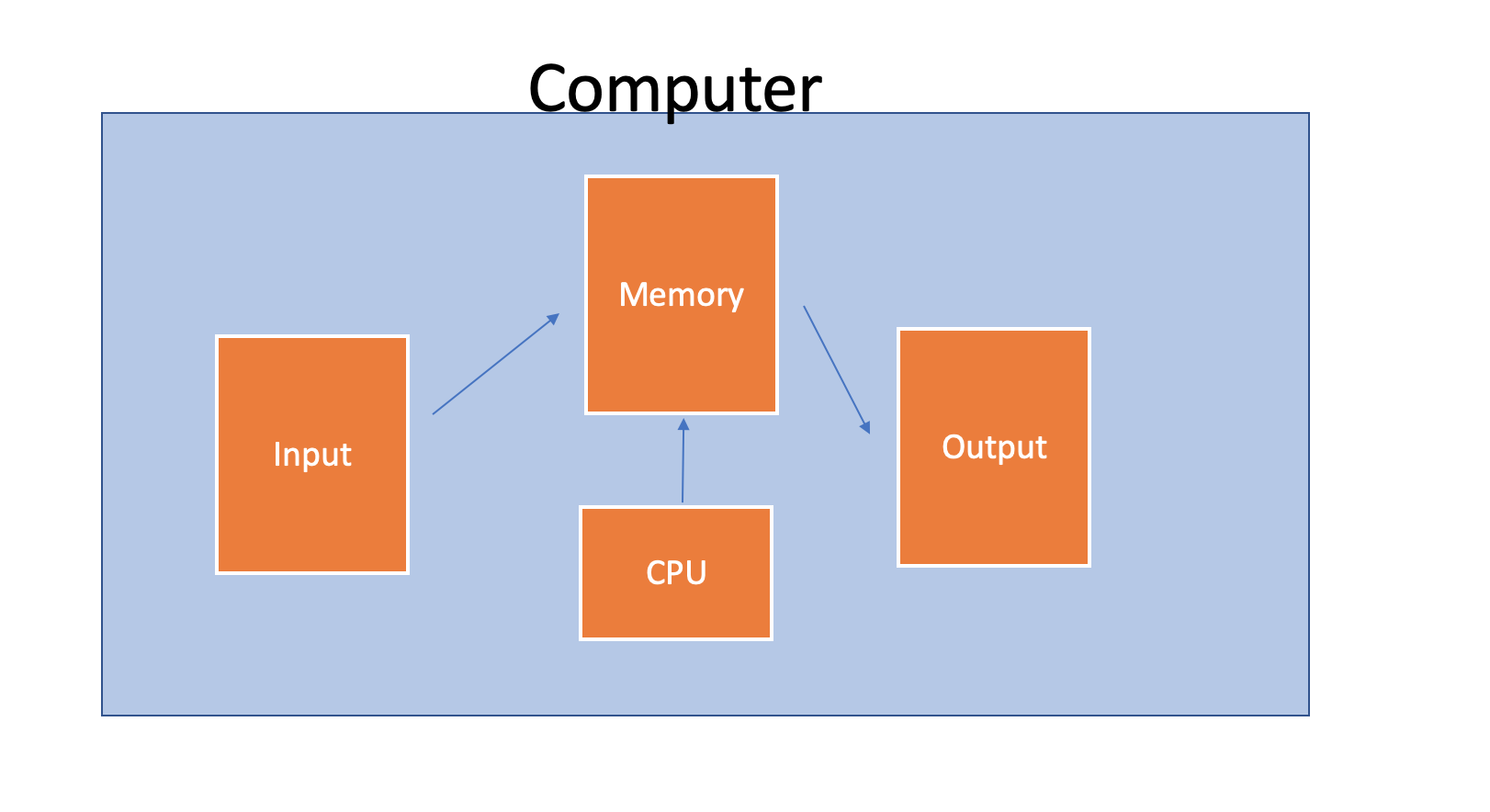

Programming languages, at their core, are a way of doing things to data using the CPU, and storing both the input and output in memory.

The CPU is pretty stupid. It can do really powerful stuff, but it only understands machine language, which, at its core, is electricity. A representation of machine language is 1s and 0s.

To get to those 1s and 0s, we need to move from our high-level, to low-level language. This is where compiled and interpreted languages come in.

When languages are either compiled or executed (python is executed via interpreter), the code is turned into lower-level machine code that tells the lower-level components of the computer i.e. the hardware, what to do.

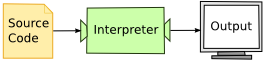

There are a couple ways to translate your code into machine-legible code: you can either build a binary and have a compiler translate it (C++, Go, Rust, etc.), or run the code directly and have the interpreter do it. The latter is how Python (and PHP, Ruby,and similar “scripting” languages) works.

How does the hardware know how to store those 0s and 1s in memory? The software, our code, needs to tell it how to allocate memory for that data. What kind of data? That’s dicated by the language’s choice of data types.

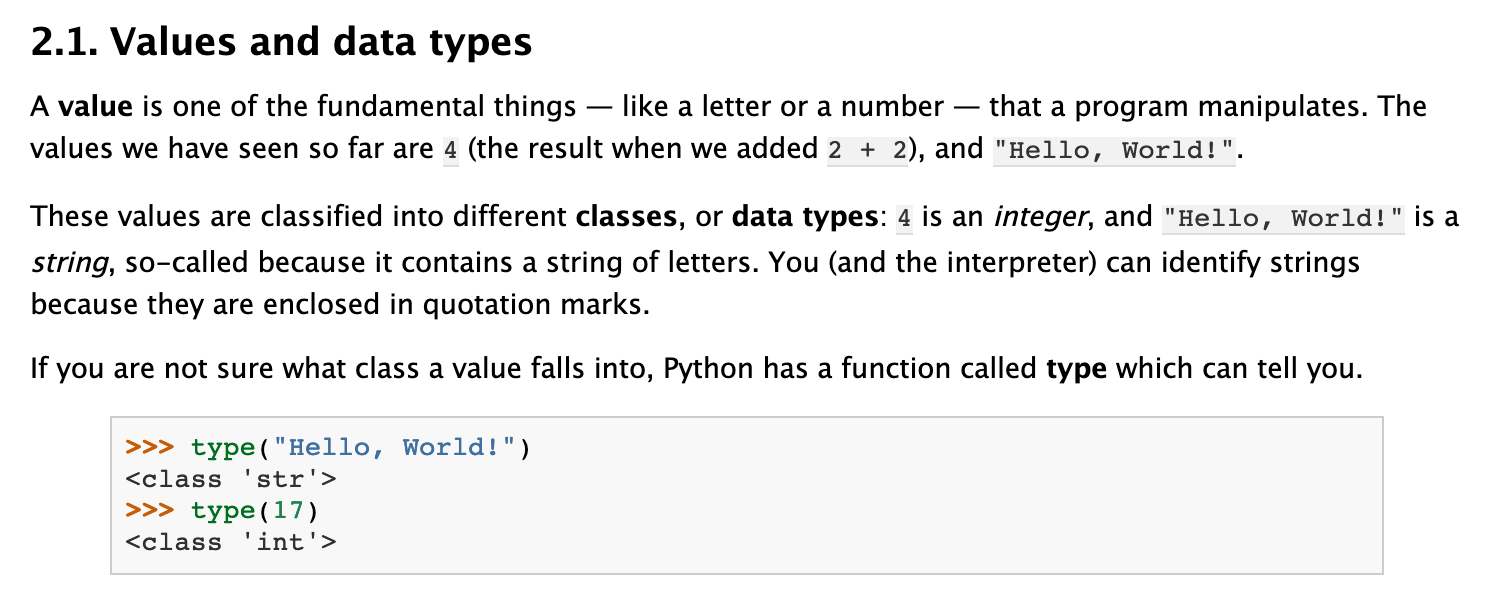

Every language has data types. They’re usually one of the first things you learn when you learn how to program.

You might see a tutorial like this (from Allen Downey’s excellent book, “Think Like a Computer Scientist.”),that talks about what they are. Simply put, they’re different ways of representing data laid out in memory.

There are strings, integers, and many more, depending on which language you use. For example, Python’s basic data types include:

int, float, complex

str

bytes

tuple

frozenset

bool

array

bytearray

list

set

dict

There are also data types made up out of other data types. For example, a Python list can hold integers, strings, or both.

In order to know how much memory to allocate, the computer needs to know what type of data is being stored. Luckily, Python has a built-in function, getsizeof, that tells us how big each different datatype is in bytes.

This fantastic SO answer gives us some approximations for “empty” data structures:

import sys

import decimal

import operator

d = {"int": 0,

"float": 0.0,

"dict": dict(),

"set": set(),

"tuple": tuple(),

"list": list(),

"str": "a",

"unicode": u"a",

"decimal": decimal.Decimal(0),

"object": object(),

}

# Create new dict that can be sorted by size

d_size = {}

for k, v in sorted(d.items()):

d_size[k]=sys.getsizeof(v)

sorted_x = sorted(d_size.items(), key=lambda kv: kv[1])

sorted_x

[('object', 16),

('float', 24),

('int', 24),

('tuple', 48),

('str', 50),

('unicode', 50),

('list', 64),

('decimal', 104),

('set', 224),

('dict', 240)]

If we sort it, we can see that the biggest data structure by default is an empty dictionary, followed by a set. Ints by comparison to strings are tiny.

This gives us an idea of how much memory different types in our program take up.

Why do we care? Some types are more efficient and better suited to different tasks than others. Other times, we need rigorous checks on these types to make sure they don’t violate some of the assumptions of our program.

But what exactly are these types and why do we need them?

Here’s where type systems come into play.

An introduction to type systems

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far, away, people doing math by hand realized that if they labeled numbers or elements of equations by “type”, they could reduce the amount of logic issues they had when doing math proofs against those elements.

Since in the beginning computer science was, basically, doing a lot of math by hand, some of the principles carried over, and a type system became a way to reduce the number of bugs in your program by assigning different variables or elements to specific types.

A couple examples:

- If we’re writing software for a bank, we can’t have strings in the piece of code that’s calculating the total value of a person’s account

- If we’re working with survey data and want to understand whether someone did or did not do something, booleans with Yes/No answers will work best

- At a big search engine, we have to limit the number of characters people are allowed to put into the search field, so we need to do type validation for certain types of strings

Today, in programming, there are two different type systems: static and dynamic. Steve Klabnik, breaks it down:

A static type system is a mechanism by which a compiler examines source code and assigns labels (called “types”) to pieces of the syntax, and then uses them to infer something about the program’s behavior. A dynamic type system is a mechanism by which a compiler generates code to keep track of the sort of data (coincidentally, also called its “type”) used by the program.

What does this mean? It means that, usually, for compiled languages, you need to have types pre-labeled so the compiler can go in and check them when the program is compiling to make sure the program makes sense.

This is problably the best explanation of the difference between the two I’ve read recently:

I’ve used statically typed languages in the past, but my programming for the past few years has mostly been in Python. The experience was somewhat annoying at first, it felt as though it was simply slowing me down and forcing me to be excessively explicit whereas Python would just let me do what I wanted, even if I got it wrong occasionally. Somewhat like giving instructions to someone who always stops you to ask you to clarify what you mean, versus someone who always nods along and seems to understand you, though you’re not always sure they’re absorbing everything.

A small caveat here that took me a while to understand: static and dynamically-typed languages are closely linked, but not synonymous with compiled or interpeted languages. You can have a dynamically-typed language, like Python, that is compiled, and you can have static languages, like Java, that are interpreted, for example if you use the Java REPL.

Data types in statically versus dynamically typed languages

So what’s the difference between data types in these two languages? In static typing, you have to lay out your types beforehand. For example, if you’re working in Java, you’ll have a program that looks like this:

public class CreatingVariables {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int x, y, age, height;

double seconds, rainfall;

x = 10;

y = 400;

age = 39;

height = 63;

seconds = 4.71;

rainfall = 23;

double rate = calculateRainfallRate(seconds, rainfall);

}

private static double calculateRainfallRate(double seconds, double rainfall) {

return rainfall/seconds;

}

If you’ll notice at the beginning of the program, we declare some variables that have an indicator of what those types are:

int x, y, age, height;

double seconds, rainfall;

And our methods also have to include the variables that we’re putting into them so that the code compiles correctly. In Java, you have to plan your types from the get-go so that the compiler knows what to check for when it compiles the code into machine code.

Python hides this away from the user. The analogous Python code would be:

x = 10

y = 400

age = 39

height = 63

seconds = 4.71

rainfall = 23

rate = calculateRainfall(seconds, rainfall)

def calculateRainfall(seconds, rainfall):

return rainfall/seconds

How does this work under the covers?

How does Python handle data types?

Python is dynamically-typed, which means it only checks the types of the variables you specified when you run the program. As we saw in the sample piece of code, you don’t have to plan out the types and memory allocation beforehand.

What happens is that:

In Python, the source is compiled into a much simpler form called bytecode using CPython. These are instructions similar in spirit to CPU instructions, but instead of being executed by the CPU, they are executed by software called a virtual machine. (These are not VM’s that emulate entire operating systems, just a simplified CPU execution environment.)

When CPython is building the program, how does it know which types the variables are if we don’t specify them? It doesn’t. All it knows is that the variables are objects. Everything in Python is an Object, until it’s not (i.e. it becomes a more specific type), that is when we specifically check it.

For types like strings, Python assumes that anything with single or double quotes around it will be a string. For numbers, Python picks a number type. If we try to do something to that type and Python can’t perform the operation, it’ll tell us later on.

For example, if we try to do:

name = 'Vicki'

seconds = 4.71;

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-9-71805d305c0b> in <module>

3

4

----> 5 name + seconds

TypeError: must be str, not float

It’ll tell us that it can’t add a string and a float. It had no idea up until that second that name was a string and seconds was a float.

In other words,

Duck typing happens because when we do the addition, Python doesn’t care what type object a is. All it cares is whether the call to it addition method returns anything sensible. If not - an error will be raised.

So what does this mean? If we try to write a program in the same way that we do Java or C, we won’t get any errors until the CPython interpreter executes the exact line that has problems.

This has proven to be inconvenient for teams working with larger code bases, because you’re not dealing with single variables, but classes upon classes of things that call each other, and need to be able to check everything quickly.

If you can’t write good tests for them and have them catch the errors before you’re running in production, you can break systems.

In general, there are a lot of benefits of using type hints:

If you’re working with complicated data structures, or functions with a lot of inputs, it’s much easier to see what those inputs are a long time after you’ve written the code. If you have just a single function with a single parameter, like the examples we have here, it’s really easy.

But what if you’re dealing with a codebase with lots of inputs, like this example from the PyTorch docs?

def train(args, model, device, train_loader, optimizer, epoch):

model.train()

for batch_idx, (data, target) in enumerate(train_loader):

data, target = data.to(device), target.to(device)

optimizer.zero_grad()

output = model(data)

loss = F.nll_loss(output, target)

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

if batch_idx % args.log_interval == 0:

print('Train Epoch: {} [{}/{} ({:.0f}%)]\tLoss: {:.6f}'.format(

epoch, batch_idx * len(data), len(train_loader.dataset),

100. * batch_idx / len(train_loader), loss.item()))

What’s model? Ah, we can go down further into that codebase and see that it’s

model = Net().to(device)

But wouldn’t it be cool if we could just specify it in the method signature so we don’t have to do a code search? Maybe something like

def train(args, model (type Net), device, train_loader, optimizer, epoch):

How about device?

device = torch.device("cuda" if use_cuda else "cpu")

What’s torch.device? It’s a special PyTorch type. If we go to other parts of the documentation and code, we find out that:

A :class:`torch.device` is an object representing the device on which a :class:`torch.Tensor` is or will be allocated.

The :class:`torch.device` contains a device type ('cpu' or 'cuda') and optional device ordinal for the device type. If the device ordinal is not present, this represents the current device for the device type; e.g. a :class:`torch.Tensor` constructed with device 'cuda' is equivalent to 'cuda:X' where X is the result of :func:`torch.cuda.current_device()`.

A :class:`torch.device` can be constructed via a string or via a string and device ordinal

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could note that so we don’t necessarily have to look this up?

def train(args, model (type Net), device (type torch.Device), train_loader, optimizer, epoch):

And so on.

So type hints are helpful for you, the person writing the code.

Type hints are also helpful for others reading your code. It’s much easier to read someone’s code that’s already been typed instead of having to go through the search we just went through above. Type hints add legibility.

So, what has Python done to move to the same kind of legibility as is available in statically-typed languages?

Python’s type hints

Here’s where type hints come in. As a side note, the docs interchangeably call them type annotations or type hints. I’m going to go with type hints. In other languages, annotations and hints mean someting completely different.

In Python 2 was that people started adding hints to their code to give an idea of what various functions returned.

That code initially looked like this:

users = [] # type: List[UserID]

examples = {} # type: Dict[str, Any]

Type hints were previously just comments. But what happened was that Python started gradually moving towards a more uniform way of dealing with type hints, and these started to include function annotations:

Function annotations, both for parameters and return values, are completely optional.

Function annotations are nothing more than a way of associating arbitrary Python expressions with various parts of a function at compile-time.

By itself, Python does not attach any particular meaning or significance to annotations. Left to its own, Python simply makes these expressions available as described in Accessing Function Annotations below.

The only way that annotations take on meaning is when they are interpreted by third-party libraries. These annotation consumers can do anything they want with a function's annotations. For example, one library might use string-based annotations to provide improved help messages, like so:

With the development of PEP 484 is that it was developed in conjunction with mypy, a project out of DropBox, which checks the types as you run the program. Remember that types are not checked at run-time. You’ll only get an issue if you try to run a method on a type that’s incompatible. For example, trying to slice a dictionary or trying to pop values from a string.

From the implementation details,

While these annotations are available at runtime through the usual annotations attribute, no type checking happens at runtime. Instead, the proposal assumes the existence of a separate off-line type checker which users can run over their source code voluntarily. Essentially, such a type checker acts as a very powerful linter. (While it would of course be possible for individual users to employ a similar checker at run time for Design By Contract enforcement or JIT optimization, those tools are not yet as mature.)

What does this look like in practice?

Type hints also mean that you can more easily use IDEs. PyCharm, for example, offers code completion and checks based on types, as does VS Code.

Type hints are also helpful for another reason: they prevent you from making stupid mistakes. This is a great example of how:

Let’s say we’re adding names to a dictionary

names = {'Vicki': 'Boykis',

'Kim': 'Kardashian'}

def append_name(dict, first_name, last_name):

dict[first_name] = last_name

append_name(names,'Kanye',9)

If we allow this to happen, we’ll have a bunch of malformed entries in our dictionary.

How do we fix it?

from typing import Dict

names_new: Dict[str, str] = {'Vicki': 'Boykis',

'Kim': 'Kardashian'}

def append_name(dic: Dict[str, str] , first_name: str, last_name: str):

dic[first_name] = last_name

append_name(names_new,'Kanye',9.7)

names_new

By running mypy on it:

(kanye) mbp-vboykis:types vboykis$ mypy kanye.py

kanye.py:9: error: Argument 3 to "append_name" has incompatible type "float"; expected "str"

We can see that mypy doesn’t allow that type. It makes sense to include mypy in a pipeline with tests in your continuous integration pipeline.

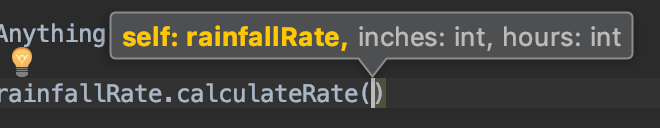

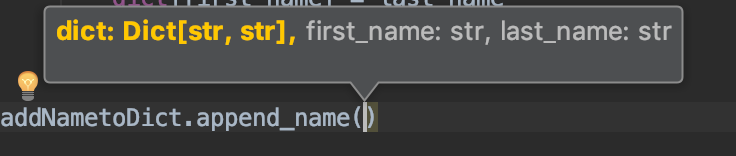

Type hints in IDEs

One of the biggest benefits to using type hints is that you get the same kind of autocompletion in IDEs as you do with statically-typed languages.

For example, let’s say you had a piece of code like this. These are just our two functions from before, wrapped into classes.

from typing import Dict

class rainfallRate:

def __init__(self, hours, inches):

self.hours= hours

self.inches = inches

def calculateRate(self, inches:int, hours:int) -> float:

return inches/hours

rainfallRate.calculateRate()

class addNametoDict:

def __init__(self, first_name, last_name):

self.first_name = first_name

self.last_name = last_name

self.dict = dict

def append_name(dict:Dict[str, str], first_name:str, last_name:str):

dict[first_name] = last_name

addNametoDict.append_name()

A neat thing is that, now that we have (liberally) added types, we can actually see what’s going on with them when we call the class methods:

Getting started with type hints

The mypy docs have some good suggestions for getting started typing a codebase:

1. Start small – get a clean mypy build for some files, with few hints

2. Write a mypy runner script to ensure consistent results

3. Run mypy in Continuous Integration to prevent type errors

4. Gradually annotate commonly imported modules

5. Write hints as you modify existing code and write new code

6. Use MonkeyType or PyAnnotate to automatically annotate legacy code

To get started with writing type hints for your own code, it helps to understand several things:

First, you’ll need to import the typing module if you’re using anything beyond strings, ints, bools, and basic Python types.

Second, that there are several complex types available through the module:

Dict, Tuple, List, Set, and more.

For example, Dict[str, float] means that you want to check for a dictionary where the key is a string and the value is a float.

There’s also a type called Optional and Union.

Third, that this is the format for type hints:

import typing

def some_function(variable: type) -> return_type:

do_something

If you want to get started further with type hints, lots of smart people have written tutorials. Here’s the best one to start with, in my opinion, and it takes you through how to set up a testing suite.

So, what’s the verdict? To use or not to use?

But should you get started with type hints?

It depends on your use case. As Guido and the mypy docs say,

The aim of mypy is not to convince everybody to write statically typed Python – static typing is entirely optional, now and in the future. The goal is to give more options for Python programmers, to make Python a more competitive alternative to other statically typed languages in large projects, to improve programmer productivity, and to improve software quality.

Because of the overhead of setting up mypy and thinking through the types that you need, type hints don’t make sense for smaller codebases, and for experimentation (for example, in Jupyter notebooks). What’s a small codebase? Probably anything under 1k LOC, conservatively speaking.

For larger codebases, places where you’re working with others, collaborating, and packages, places where you have version control and continuous integration system, it makes sense and could save a lot of time.

My opinion is that type hints are going to become much more common, if not commonplace, over the next couple years, and it doesn’t hurt to get a head start.

Thanks

Special thanks to Peter Baumgartner, Vincent Warmerdam, Tim Hopper, Jowanza Joseph, and Dan Boykis for reading drafts of this post. All remaining errors are mine :)