Getting machine learning to production

Art: The Other Side of the Rainbow, Roland Petersen, 1972

Table of Contents

- Intro

- The Mystery of Deploying ML

- Trying to Create Gandinsky

- Trying to Create Venti

- Venti Architecture

- Putting Venti on Streamlit

- Splitting out inference and front-end

- Deploying to the Cloud

- Lessons Learned

I haven’t seen many posts in the wild on how end-to-end machine learning works, so this post covers the process of creating an end-to-end proof-of-concept (POC) machine learning product, Venti, which is a Medium-like site that generates VC thinkpieces.

All the code for serving the model is here, and here for generating inferences.

The app, Venti, is live here.

Intro

A few months ago, Emmanuel Amiesen sent me a copy of his book, Building Machine Learning Applications.

Just got this in the mail from @mlpowered and looking forward to digging in (maybe when I’m getting > 5 hours of continuous sleep.) It looks great so far and what I like about it is that explains common ML prod jargon like “inference” and “data leakage.” Thanks, E! pic.twitter.com/3PDU8Ev0Ja

— vicki (@vboykis) February 10, 2020

I read it with a lot of interest because there is not a lot of “official” literature out in the field about what machine learning orchestration and pipelines should look like.

As I wrote in a newsletter a while back,

There really is no good, generalized single system of best practices for creating machine learning platforms. There’s not even a textbook on it. (Other than Designing Data-Intensive Applications, which is good but doesn’t necessarily fit the bill.)

Much like the steam-powered tricycle, each machine learning project is beautiful and weird and inefficient in its own way. Every company has its unique set of needs, stemming from the fact that each company’s data and business logic run differently. In a recent Hacker News threads on how models are deployed in production, there were over 130 different answers, ranging from using scikit-learn, to Tensorflow, to pickling objects, to serializing them, to AWS Lambdas, to Kubernetes, to even C#.

This lack of standardization, and more importantly, lack of stories about standardization, leads to a lot of reinventing the wheel and gluing things together, across the industry.

I wanted to see if Building Machine Learning Applications addressed some of that. It’s an interesting book, and I recommend it particularly if you are new to machine learning systems and processes, or a team trying to standardize on some set of processes.

Some of its most salient points include:

- reasoning through which features to build

- how to starting with small groups of data in-memory before working with terabytes of data on a cluster

- the nuances of working with continuous features

- normalizing features (so they’re scaled between 0 and 1), and

- things to watch out for, such as data leakage (data from outside of your test set making it back into your test set and biasing the results)

However, I felt it was missing one key piece: the deployment story. There is a chapter on on deploying the model , but it’s not anywhere near specific as I would like, which I think makes sense.

The Mystery of Deploying ML

It’s hard to account for all the particular use cases and ways to deploy a machine learning model.

To be fair, Kleppmann’s (very good) book,which I mentioned in that newsletter, doesn’t really delve into the details, either.

As I wrote in that review,

Kleppmann very clearly knows absolutely everything there is to know about distributed systems, from soup to nuts. The amount of topics he covers in his book - from - from text encoding, to database data structures, to partitions, - is truly staggering. But I came away disappointed, because what I was really looking for from the book was a set of heuristics that would tell me how to start at the basement of a distributed system and work my way up to understanding how the various components fit and work together. What I wanted was a blueprint for how to build a house, and what I got instead were comprehensive chapters on different power tools.

But my experience has been that deploying a machine learning model is always much harder than building it or reasoning about the technical, mathematical parts of the model, and that there is not a lot of literature about this specific piece out there.

Many blog posts assume you know how to get from 0 to production.

As I write this, several projects have arisen that are looking to deal with this, including Made with ML and Feature Stores for ML, which talk specifically about the data needed for the model, but the landscape for best practices is still a little sparse.

So, this post goes into the nitty-gritty reasoning that I’d like to see in other examples on this topic.

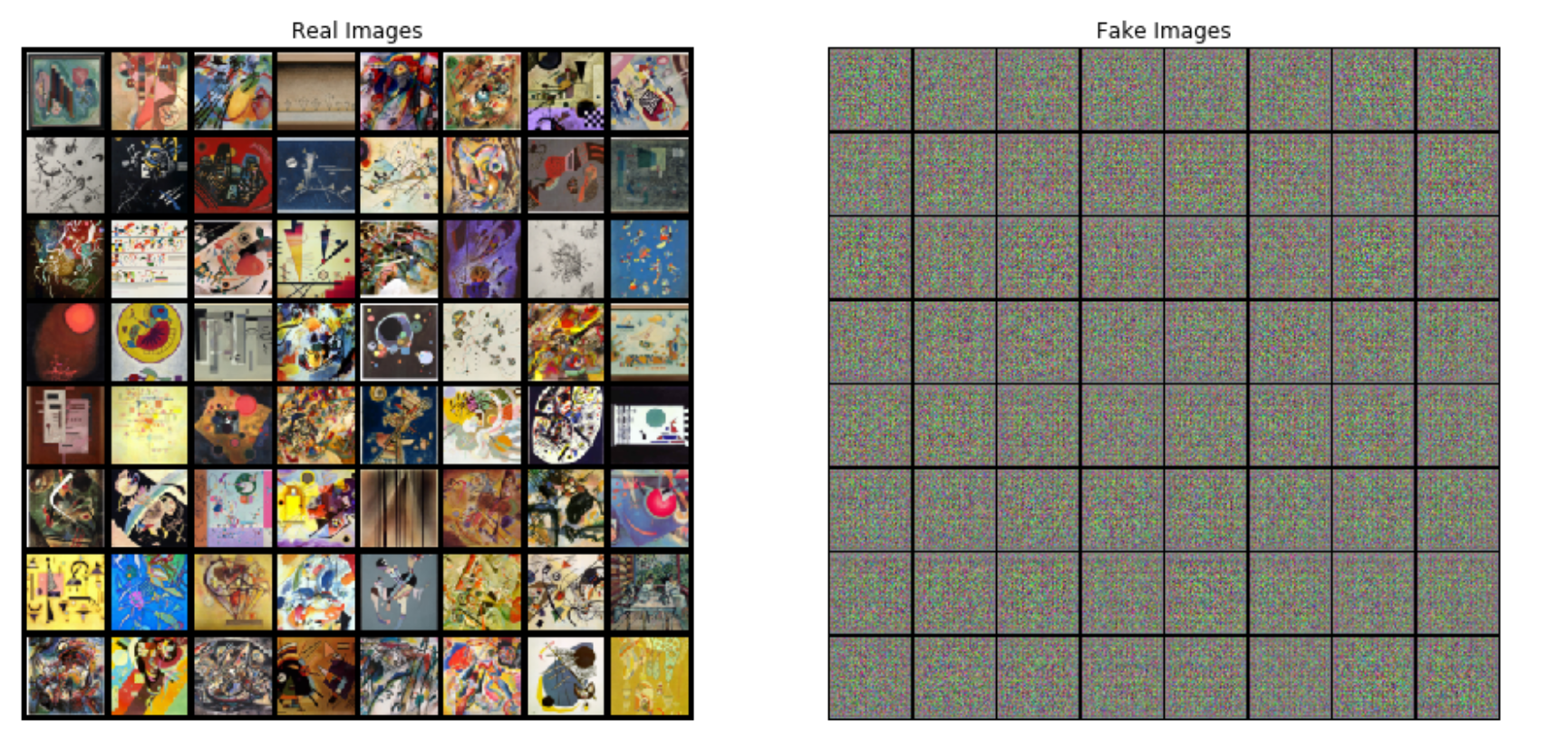

Trying to Create Gandinsky

A couple months ago, I decided I wanted to learn PyTorch. It’s unlikely I’ll come across a use for it immediately, but it never hurts to know for future projects. More broadly, and it always helps to know what a popular technology does so you can recommend a move for it or against it when you look at different technologies.

I first started by perusing the fast.ai course on deep learning, and checking out Brandon’s courses and lectures to get an idea of what you could do with deep learning and how to think about it intuitively.

Then, I got an idea. My daughter is really into Vassily Kandinsky right now, and after reading this wonderful book, I thought would try my hand at generating new Kandinsky art.

I wanted to use a GAN, a generative adversarial network, which is a neural net that can generate new images from a given set of training data. Then, I’d make a web app serving the model so that people could press a button and the underlying neural net would generate its own Kandinsky art that they could then share or tweet, or whatever.

Here was what I thought he workflow would look like:

Luckily, PyTorch offers an implementation of GAN called DCGAN that already does something extremely similar to what I was looking to do, and I looked to use that as a starting point.

However, what happened when I downloaded the data from the Wikiart API and trained the model, and put it into the model, I got back a ton of white noise.

After doing some research, I realized this was because Kandinsky unfortunately only painted something like 250 works of abstractionism in his lifetime.

And, for a GAN to be effective, you need to feed it at least a thousand pieces of work. Which is why the DCARtGAN works, but Gandinsky doesn’t.

In theory, I could have bootstrapped the dataset, or used a larger set of abstract art that was more than just Kandinsky’s works, or potentially done transfer learning based on ImageNet, which does have a lot of images (over 1 million.)

But, I didn’t want to dig into this specific problem yet, because I knew that if I did, I’d get bogged down in the machine learning implementation itself and not make any progress forward on putting the project into production.

I was looking more to understand how PyTorch and deep learning fit into deploying a machine learning application that ran. So, I decided to pivot, and again began brainstorming.

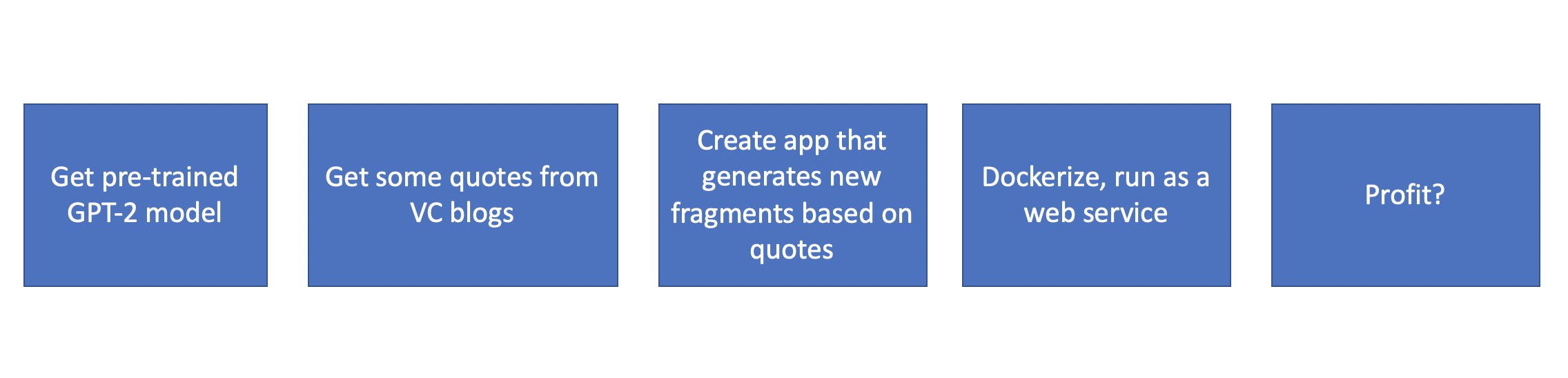

Trying to Create Venti

What could be an easier thing I could put into production?

After researching deep learning models, I remembered Hugging Face. They focus specifically on NLP, natural language processing, or generating and predicting new text using an input corpus and some deep learning.

What’s even more helpful is that Hugging Face offers pre-trained NLP models, for free.

The reason this is such a big deal is that it takes an enormous amount of processing time and computing energy to train deep learning models for the first time. If you want to get to an MVP quicker, it’s great if there’s a pre-trained model available for you to use (again, if it makes sense and fits your use case.)

One of the models HuggingFace has is GPT-2. GPT-2 is a model developed by OpenAI that basically scraped the entire internet and can do text prediction based on that. (Since then, GPT-3 is also available, but it came out a couple weeks after I finished this model. )

What really sweetened the deal was that I also found that there was a nice wrapper around HuggingFace’s implementation of the pre-trained model available for PyTorch. That’s what I decided to use for my MVP.

What could I make with a text generator? Recently, I’ve been reading a great newsletter, Tech Twitter TLDR, that covers VC tweets, ranging from the funny to the ridiculous. There is always something a little surreal for me in watching VCs opine from their towers, a bit disconnected from reality, on what’s going on in the rest of the country, and I decided to have a little fun with that.

I decided I wanted to see if I could make an NLP app that would write a VC’s thinkpieces based on beginning sentences of their actual writing. And that’s how the idea for Venti started.

The idea behind Venti would be that it would be a small, light app that looked a bit like Medium (Venti being the fancy Italian word for Medium).

You’d be able to put in some phrases from VC blog posts, and it would generate an essay for you that you could then share or reload.

Like this:

Seemed easy!

Now, for how to actually do it.

Venti Architecture

I downloaded a package that had an easy-to-use wrapper around HuggingFace’s pre-trained gpt-2 Pytorch implementation. What it does is loads the model with torch.load and then let you perform inference (predictions) on it at the command line.

The key is here:

def text_generator(state_dict):

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument("--text", type=str, required=True)

which takes the state_dict variable:

torch.load('gpt2-pytorch_model.bin', map_location='cpu' if not torch.cuda.is_available() else None)

and loads the model from memory

(torch.load('gpt2-pytorch_model.bin', map_location='cpu' if not torch.cuda.is_available() else None))

It then loads the weights for the model, and generates a batch of text for you based on the number of input words you specify.

The specifications of the model itself are in the GPT2 directory, and the main script calls the model.

When you run it in command line argument mode, it generates text for you:

python main.py --text "It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen. Winston Smith, his chin nuzzled into his breast in an effort to escape the vile wind, slipped quickly through the glass doors of Victory Mansions, though not quickly enough to prevent a swirl of gritty dust from entering along with him."

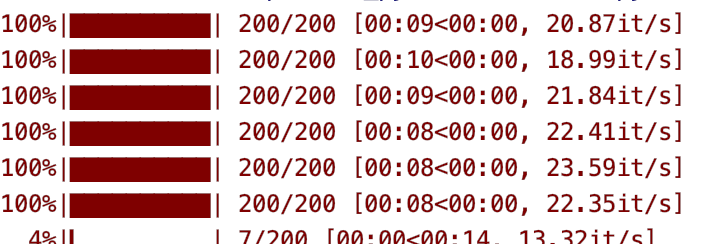

Generating Venti Inferences

Once you can generate model outputs that make some reasonable sense at the command line, it’s time to modify it by offering your own inputs.

I started by thinking about what I’d want to generate in a programmatic manner for my think piece app, and I ended up with a (Pythonic) list of sentences that I took from several VC blog posts.

quote_list = ["The startling thing is how often the founders themselves don't know. Half the founders I talk to don't know whether they're default alive or default dead."]

I started my exploration in a Jupyter notebook. (By the way, if you’re looking for tips on how to do venvs in Jupyter notebooks, check out my post here).

And, I started getting outputs. (I wrapped all of this in JSON. )

"phrase_3": "The startling thing is how often the founders themselves don't know. Half the founders I talk to don't know whether they're default alive or default dead. The other half don't know what to do. The other half know what they should do (and don't want to do). Those who don't know their own behavior are also often the ones who are the ones who are the ones who are the ones to do things to the founders of all their companies.\n\nThe founders of their companies aren't the ones to ask and don't want to ask or want to get involved with. In fact, they're the ones who are the ones to decide what they want to do. The founders of most of their companies are the ones who care about the founders. Most of their companies are the ones who are the ones to decide what they want to do.\n\nSo what's the difference between going to the founders and going to the founders, actually?\n\nThe founders of the companies they're building are the ones who are the ones to decide what they want to do."

Now that I could generate model outputs based on my own inputs, on my computer, it was time to take my JSON off my local machine, and into the cloud.

I’d need to refactor it so that it didn’t depend on a person manually running it with command line arguments, and so that non-developers who weren’t familiar with JSON could see the output in a human-friendly way.

Putting Venti on Streamlit

When you look at front-ends for machine learning apps these days, we’re still very much in the early days, which is a shame, because the most important part of building a model is actually showing some results.

You could use Tableau, but that’s not really for visualizing machine leanring results as much as report results from a database. You could use Looker, or AWS’s Quicksight, but none are really flexible enough to show dynamic results for a changing model, particularly one with visuals.

Really, every time you want to show any kind of interactive results, you either have to build out your own web app and become a front-end developer by using something like Flask, or Django, or another web framework. You have to serve up the front-end with Bootstrap, and if you’re not a full-stack developer, as I am not, you spend just as much time fiddling with that stuff as your actual work.

This is where Streamlit comes in. Streamlit is a framework built in Python that creates a web server and a way for you to send whatever it is you’re working on through to the front end. It’s open-source, and I’m assuming they’re going to monetize by deploying for teams and private hosting.

I’ve been hearing about Streamlit for a while now, but have only had the chance to play with it recently, and I’m sold. It’s really, really easy to get started locally and display some very nice-looking dashboards.

So, once I found the GPT-2 code, I set about adapting it so that it could be used with Streamlit.

First, I started by wrapping the main script’s return values in Streamlit calls,

more specifically, here:

for i in range(batch_size):

generated += 1

text = enc.decode(out[i])

st.markdown(text)

so that every time a string was generated, it would go out into the Streamlit UI via Markdown formatting.

However, here I came to a problem. Each inference point took about 5 seconds to generate.

On my computer, it was fine, if a little annoying in my development cycle. In a realtime environment, this is unacceptable. Let’s say one person hits your web server. Fine. But what if even five people need the results of this model?

If I were, for real going to production, there are several ways I could have approached troubleshooting the lag:

- Digging into the PyTorch code to see if it was an issue with the model

- Using a smaller subset of GPT-2 and to build a smaller model

- Caching the model results every time

- Moving to GPU-based inference (I’d only been using my laptop, which didn’t have GPUs enabled)

- Turning with hyperparameters until the timing for each piece went down

However, since I was working on a POC, I went the brute-force way: I decided to split the project into two: one that generated a batch of inferences and spit out a json, and the actual code that ran on the server that ran the app, which would ingest that JSON and generate a phrase.

https://github.com/veekaybee/venti/blob/e87c6dead0d6283db00f27eaed2d5579d43b564e/streamlit.py

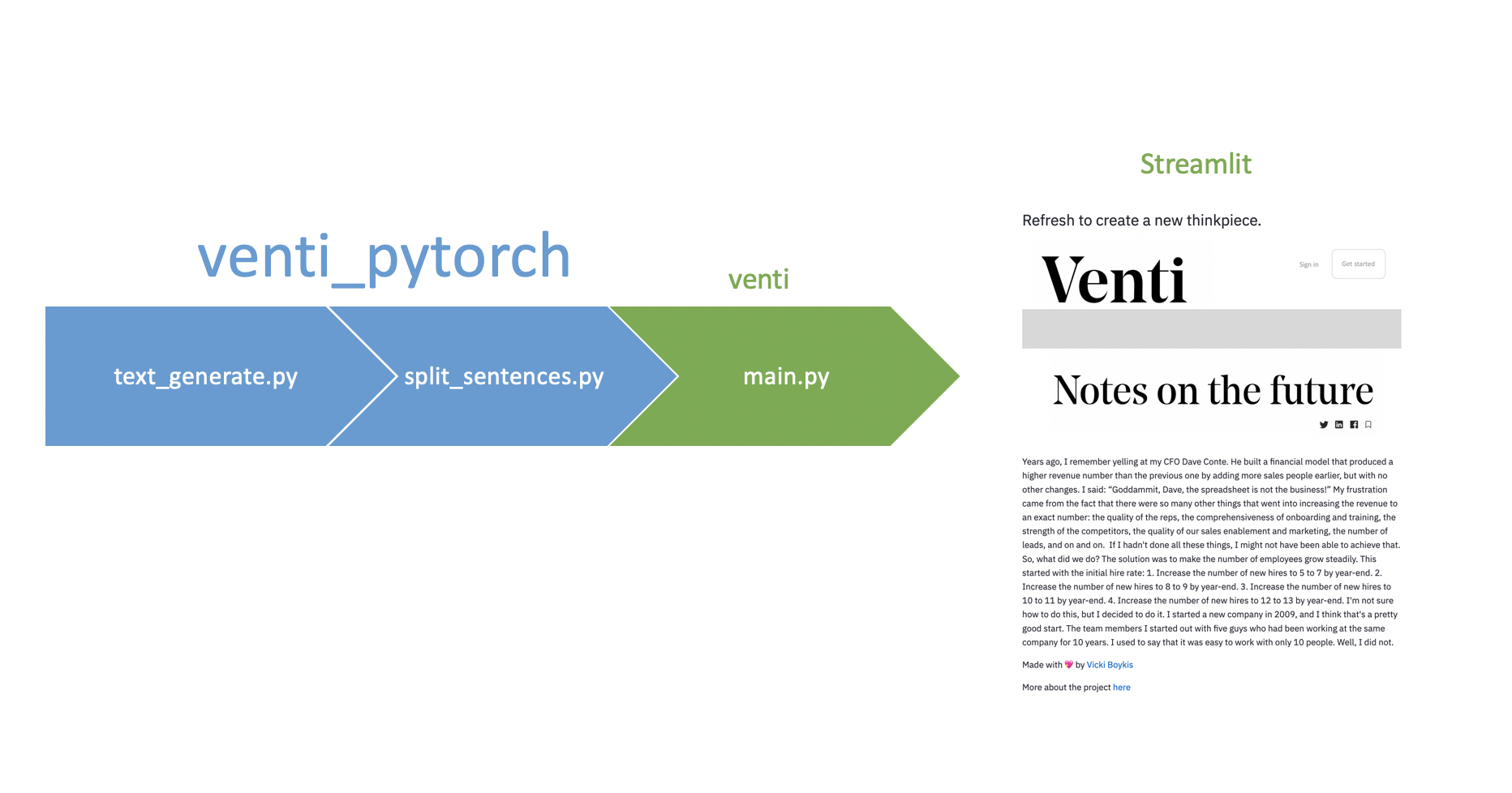

Splitting out inference and front-end

Now, this is kind of a counterintuitive use of Streamlit - since I’m not doing inference or interactivity, I could use any kind of framework, like Flask, for it, but Streamlit really is as easy as running a couple lines of code and giving you nice outputs, so that’s what I decided to do.

It seemed like, at this point, it made sense to separate inference from the customer-facing tool. So, I created two projects, and split out venti, which would be my customer-facing app:

venti

├── Dockerfile - Dockerize it

├── README.md

├── __pycache__

├── gpt - virtualenvironment

├── requirements.txt

├── src

│ ├── fixed_generated_phrases.json - json of thinkpieces

│ ├── main.py - program to run Streamlit

│ └── venti.png - image

└── task-definition.json - GitHub/AWS component

and my internal, inference-generating app:

venti_pytorch

├── GPT2 - the actual code generating the model

├── LICENSE

├── README.md

├── __pycache__

├── fixed_generated_phrases.json - json that goes to venti

├── generated_phrases.json

├── gpt2-pytorch_model.bin - the GPT2 pre-trained model

├── quotes.py - initial input quotes

├── requirements.txt

├── split_sentences.py - cleaning up the text

├── text_generate.py - model that generates text

└── venv

The process flow went something like this:

First, venti_pytorch.text_generate.py generates a batch of 50 phrases, then venti_pytorch.split_sentences.py cleans them up. Then, the generated_phrases.json doc goes into the venti folder, where main.py picks it up and runs Streamlit.

So, here’s my very manual pipeline:

Deploying to the Cloud

{< tweet 1237909940305571840 >}}

{< tweet 1235999032574648321 >}}

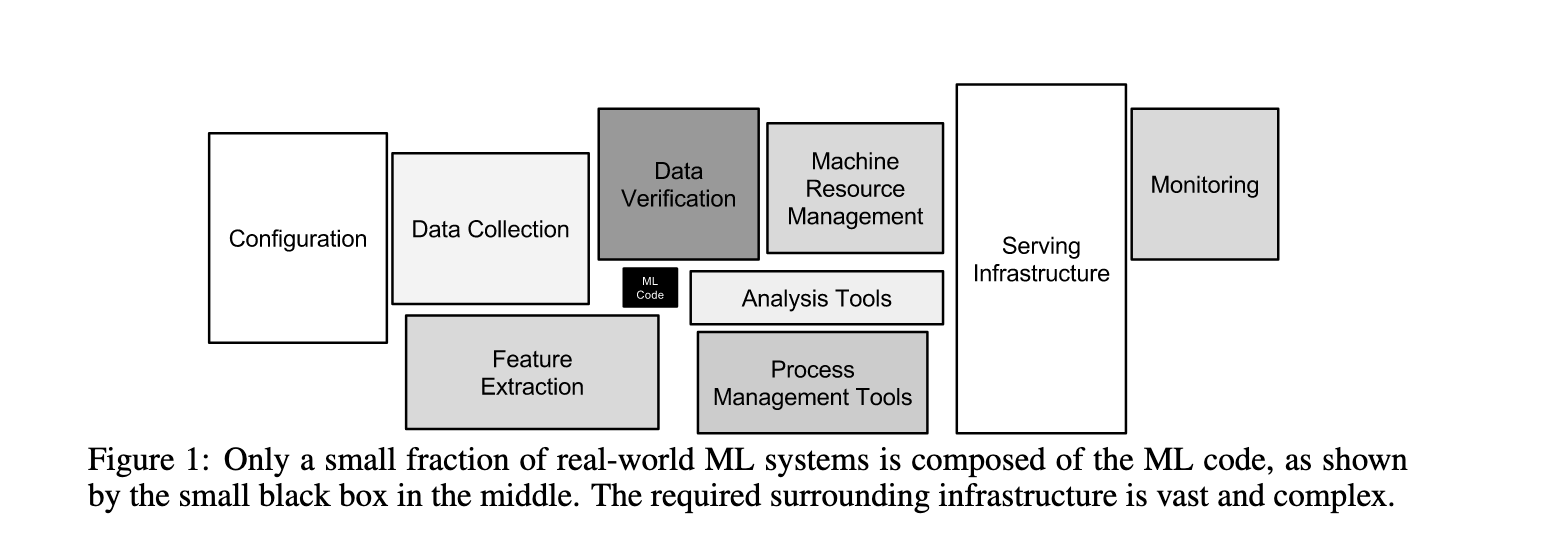

Deploying machine learning products to production is always the trickiest part of the process. It’s very, very, very hard, as this paper covers in really good detail.

Why? Because you’re not only deploying software, you’re also, in essence deploying data, that moves between various departments, in various formats, that changes as the model changes, and there are a ton of moving variables in the system that impact the other variables.

For my codebase, all I had was a “simple” Streamlit web app exposed on port 8501 that had to be stood up in some kind of virtual fashion, that I could update quickly as I pushed to Git.

I didn’t even have to deal with live inference, model drift, user inputs, measurability bias, or streaming data sources.

And still, it took me a really long time, because I had to figure out how to make my Streamlit app easy to run, relatively secure, and at least somewhat under CI/CD so I could make changes quickly and test them.

There is a good tutorial about quickly deploying Streamlit to an EC2 instance, but that’s not what I wanted to do here.

Because that code asks you to install a number of libraries and applications on the EC2 instance. That’s not easily reproducible in case we have to tear the instance down and start again.

If we tear the instance down, we lose all our code and infrastructure on it. In theory, we could have put the code on detachable EBS block storage, but there was an even more resilient way that didn’t tie me to the AWS ecosystem, and that I could also use locally.

What we want is for this web-app to be self-contained so we can deploy it anywhere. I had to Dockerize it. What do we mean when we say to Dockerize an app? We mean that we put the directions for how to run the app in a Dockerfile, run the Dockerfile, and the app runs in the container, which is a Linux virtual process, instead of on the actual server.

If you’ve ever used Python virtual environments, the concept is very similar. Why do we do this? Because installing stuff on the actual machine is hard, annoying, and we won’t have the same machine every time. Docker guarantees that the process we run has the same, identical environment, every time.

In this case, you don’t need to create virtual environments like you do locally, you can put everything you need in the Dockerfile, like so:

FROM python:3.7

EXPOSE 8501

WORKDIR /venti

COPY requirements.txt ./requirements.txt

RUN pip3 install -r requirements.txt

COPY . .

CMD streamlit run src/main.py

What this does is expose port 8501, the default port that Streamlit uses, to the machine you’re running the code on. It then copies everything into the container and uses streamlit to run the main program.

Once this code was working locally, it was time to put this Docker container somewhere so it could run on a server.

AWS, unsurprisingly, has many options for working with Docker containers, and all of them are confusing.

You can use plain EC2, but then you have to manually push your container every time you update it, and tear down and build a new image. Or, alternatively, spend time orchestrating this process, which also takes up time.

You can use Elastic Beanstalk, which is like Heroku, in that you can put a Docker container on a server, but it doesn’t allow for some kinds of flexibility.

Or, you can use ECR and ECS, which the route I ended up going with, combined with GitHub actions.

ECR is the container registry, so the Docker container goes there once you’re done building it locally. ECS, the AWS Container Service, actually manages and runs the container process. Elastic Beanstalk runs on ECS, but ECS itself gives you more fine-grained controls.

So, what you have to do is set it up so that when you push your code, it creates a Docker container that is uploaded to the container registry, and then the container registry pushes and starts that container in ECS, which spins up managed EC2 instances.

And, finally, all of that is connected through a GitHub Actions push, which orchestrates the setup.

PHEW.

It looks something like this:

and the process basically works like this,

- You build your Dockerfile/make changes to your application

- You do a GitHub push

- GitHub reads your .github/workflows folder for a build spec. Mine looks like this, and you can find some similar examples for your necessary workflow in GitHub actions.

- It then logs into AWS with secrets that you put in your GitHub repo, and sends a new container to ECR

- It builds the container, pushes the image to ECS, and replaces the task definition.

- Then, you change out the task definition and your app refreshes.

Once I had all that done, my app was ready. (Easy peasy, right?)

And, voila!

Lessons Learned

I learned a ton while building this thing out. The biggest impediment is that there are so many moving parts that go into building even a simple machine learning prototype, that it would be impossible to include all of them in a book and have that book be detailed enough.`

Even in this post, as detailed as I tried to make it, I left out:

- How to tune the model

- How to store features

- How to set up CI/CD correctly

- A Git branching strategy for when you’re working with others

- Details about my Jupyter notebooks

- Details about command-line argument parsing in Python

- The architecture of ECR and ECS, and what you might use instead in an Azure or GCP world

- How Streamlit works in detail and what you might use instead (Flask, perhaps, with some light front-end)

- A strategy for scaling the number of users (load balancing)

- Testing, both unit and integration, for machine learning models

- Container best practices

and on and on and on. Machine learning engineering is not just a world, it’s an entire universe.

The other problem is that the landscape is changing so quickly that one methodology or recommendation is often out of date as quickly as stuff comes to press. For example, in the process of writing this blog post over several months, GPT-3 came out, as did a new version of Python, and several new AWS services, including improvements to Sagemaker. It’s a lot to keep up with.

Here are some of my other, general learnings.

Deploying is hard

I think my most important lesson is one that I knew already, but one that I just had confirmed: deploying stuff is really, really hard, but the most important part. But usually, in trying to get all the other details going - tuning hyperparameters, cleaning the data, doing metadata changes, picking the correct tools, challenging your model assumptions - production is the last thing that happens and the last thing that goes out the door. This is often why it’s rushed, and why it’s a problem.

Deep learning is deceptively easy

There are a lot of pre-trained models and code out there. The hard part is making sure you understand what the code is doing so you can optimize it if you need to, and tune it for accuracy.

For example, Venti right now spits out some really bizarre things. If I wanted to follow up on it, I’d tune it, or retrain it on a smaller/different dataset to get more specific VC answers.

Go for prebuilt as much as possible

You can write your own deep learning code from scratch, for sure. If you’re a researcher, this is a strength, because you can really fine-tune your model. For most people, they don’t need to build their own transformers or reimplement gradient descent.

You need to, most importantly, be able to evaluate whether the prebuilt model that exists is going to work for you, if it includes any inherent biases that will drastically negatively change the business outcomes of your models, and whether you can rely on it.

Understand networking and scale

Ironically, the part that I was most stuck on was figuring out how to get the container port to reflect the machine port and echo out through the process. Networking and all of the surrounding infrastructure that we work with, both in the cloud and in on-prem environments can usually be a big holdup to getting stuff into production.

The more you, as a machine learning practitioner, understand about your network topology, servers, and ports, the faster things will go.

Iterate quickly

There is so much going on here, it’s easy to get bogged down in details, and I did, for a number of months.

The best thing to do is to build something quickly first, like I did here, and work on making it better.

I wrote in a previous post,

One of my favorite books ever is Bird by Bird, by Anne Lamott. It’s about how to write. The story she tells in the book, of how the book got its title, is a book report her brother had to write.

“Thirty years ago my older brother, who was ten years old at the time, was trying to get a report on birds written that he’d had three months to write. [It] was due the next day. We were out at our family cabin in Bolinas, and he was at the kitchen table close to tears, surrounded by binder paper and pencils and unopened books on birds, immobilized by the hugeness of the task ahead. Then my father sat down beside him, put his arm around my brother’s shoulder, and said. ‘Bird by bird, buddy. Just take it bird by bird.’”

And he got it done.

Good luck! You can do it, too.

#machine learning #production #engineering #deployment #data science