The humble hash aggregate

This post is an expansion of this tweet:

One of the important ways we learn when we’re growing up is by understanding patterns. As a mom of two young children, I’ve been lucky enough to witness this happen multiple times in the wild. Recently, my youngest, who is almost two, has learned the Russian word “еще”, or “more.” He’ll say it when he wants a second (or third) slice of watermelon. He’ll also say it when he opens the shoe closet and sees one sandal, and then another one, and another one.

It’s always amazing to watch children learn about the world. Children need to understand patterns to understand how their world is structured,

We find patterns in math, but we also find patterns in nature, art, music, and literature. Patterns provide a sense of order in what might otherwise appear chaotic. Researchers have found that understanding and being able to identify recurring patterns allow us to make educated guesses, assumptions, and hypothesis; it helps us develop important skills of critical thinking and logic.

The same is true for adults, too, and doubly so for those of us who work with data. We need to have a historical understanding of the patterns that our industry has applied and used so we can make flexible, resilient systems. In a previous essay in Increment, I wrote,

Indeed, technologists often enter the industry without any knowledge of how the work has been done before—a fact that isn’t helped by the breathless pace of technological change. Early-career engineers may have to evaluate Redshift versus S3 versus HDFS versus Postgres for storing their data within the cadence of a sprint cycle, not realizing that, while all have their specific use cases, Redshift and Postgres are driven by the same relational hierarchy, S3 and HDFS share a similar folder-like architecture, and most people choose to move to relational models in the long run.

Because few come into their roles with the historical and contextual knowledge they need to design and implement effective software architecture, developers must instead gather that information proactively. Keeping a rotating list of architectural patterns (and their backgrounds) in mind can head off the need to rework and prevent architectural misfit.

This is one of the reasons that most software engineering (and, now, machine learning engineer) interviews now have a portion around whiteboarding algorithms. Algorithms are the way we understand and pass down patterns in software engineering.

But what about data interviews? Why, so often, do MLE interviews, particularly in FAANG companies, come up with the same list of algorithms to discuss as software engineers - linked lists, graphs, and binary trees - when much of the work we do is only tangentially related? How does knowledge of these patterns and sharing that knowledge back out in interviews help us at work on a day-to-day basis?

There’s been a lot of digital ink spilled, including by me, about how clumsy and inefficient these kinds of interviews are for actually assessing what you want to find: a technically competent person who is eager to learn and who you wouldn’t mind working with day in and day out.

But the issue is that all this data stuff is new, and we don’t have a good way to contextualize the patterns we work with on a day-to-day basis. It’s true that data work is moving closer and closer to engineering, so the more we understand and use fundamental software engineering concepts, the better off we’ll all be.

Hash Aggregate Here

But data work also has its own unique patterns, and I want to talk about one of these that I think is important for all of us to carry around in our back pockets: the humble hash aggregate. The hash aggregate works like this:

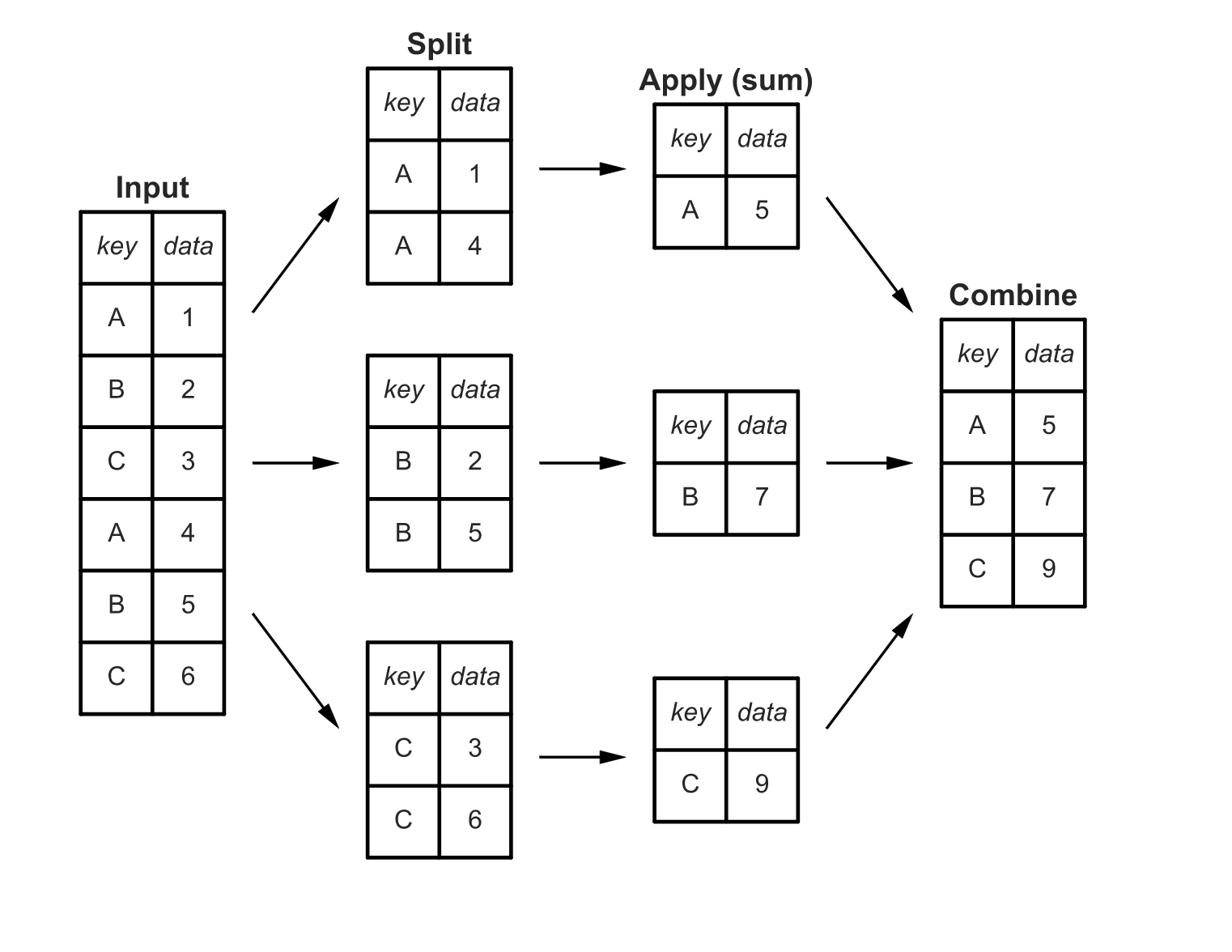

You have a multidimensional array (or, as us plebes say, table) that contains numerous instances of similar labels. What you want to know is the distinct counts of each category. The implemented algorithm splits the matrix by key and sums the values and then returns the reduced matrix that has only unique keys and the sum values to the user.

It’s a very simple and ingenious algorithm, and it shows up over and over and over again. If you’ve ever done a GROUP BY statement in SQL, you’ve used the hash aggregate function. Python’s dictionary operations utilize hash aggregates. And so does Pandas’ split-apply-combine (pictured here from Jake’s great post) And, so does Excel’s Pivot table function. So does sort filename | uniq -c | sort -nr in Unix. So does the map/reduce pattern that started in Hadoop, and has been implemented in-memory in Spark. An inverted index, the foundation for Elasticsearch (and many search and retrieval platforms) is a hash aggregate.

So what?

If you’ve worked with either development or data for any length of time, it’s almost guaranteed that you’ve come across the need to get unique categories of things and then count the things in those categories. In some cases, you might need to build your own implementation of GROUP BY because it doesn’t work in your language or framework of choice.

My personal opinion is that every data-centric framework that’s been around long enough tends to SQL, so everything will eventually implement hash aggregation.

Once you understand that hash aggregation is a common pattern, it makes sense to observe it at work, learn more about how to optimize it, and generally think about it.

Once we know that this pattern has a name and exists, we have a sense of power over our data work. Confuscius (or whoever attributed the quote to him) once said, “The beginning of wisdom is to call things by their proper name," and either he was once a curious toddler, or an MLE looking to better understand the history and context of his architecture.