The local minima of suckiness

Key and Hand, Tamara Lempicka, 1941

I don’t usually deal in absolutes, but I now know this one thing to be fundamentally true: no one becomes a good software engineer by themselves. But in an industry that has always prided itself on the myth of the superstar ninja, the lone wolf, the self-taught genius, it can seem like good developers are not born - they rise out of the ground, fully-formed and churning out PRs in their wake.

In my career so far, I haven’t seen a single person who has been able to grow successfully as a competent developer without learning from others. And, I’m concerned that, as an industry, we don’t often actively talk about the fact that we need other people at work to help us learn things, and that we need room for this learning in our development and work planning processes.

In “Rise of the Expert Beginner”, an essay that I re-read every couple of years, Erik talks about how developers stop learning. His basic thesis, based on previous studies of skill acquisition, is that people start acquiring skills very quickly. But, at some point in the learning process, they get to a point where they stagnate because the skills that they learned as a beginner will carry them to being an expert.

Think about the difference between being able to write functions that print out to your terminal versus creating a class with methods that return text to pass to other methods that checks for sanitized inputs, and then passes it to a front-end. Now imagine that that class is a function that has to be packaged to work in the cloud. And, on top of that, imagine that the function has to be version-controlled in a repo where 5-6 people are regularly merging code, pass CI/CD, and is part of a system that returns the outputs of some machine learning model with latency constraints.

You can write print statements in any language pretty quickly (given that you get over the hump of installing it on your local machine). But it takes a very long time to understand how to get from print(“Hello World”) to “Here’s an app that is making machine learning predictions for you in real-time.”

So how do we get everyone on our teams to that place? How do we help others get out of the dark, frustrating place that is the local minima of suckiness that is the expert beginner, past the stars, and into the cloud? And, how can we help ourselves become better developers?

There are three things that I’ve noticed in my own career that developers need to become better:

- the room to make mistakes

- repeated exposure to best practices, and

- understanding how to ask good questions, or learning how to learn

The room to make mistakes

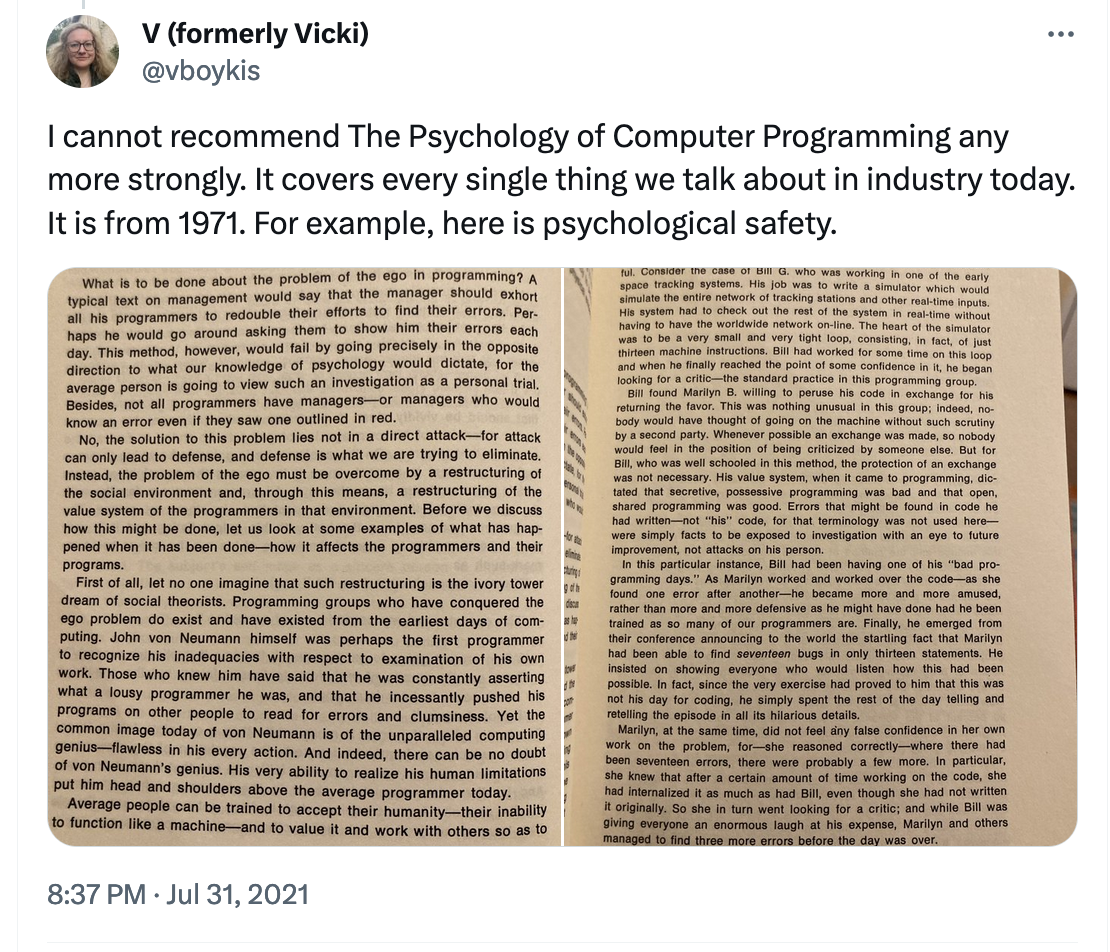

This is the best recent description I’ve found of the phenomenon we now call psychological safety.

The simple story is that, in a good, productive software environment, you have the room to mess up. The apocryphal story about how this works is the one where the junior developer breaks production, costing the company thousands of dollars. After he sees this, he starts putting everything on his desk in a box. The CEO comes up to him and says, “Where are you going?” “I just cost the company so much money, I figured I was fired.” “We just paid thousands of dollars to train you. Why would we let you go?”

Here’s another real one one, from an amazing book I’m reading, Gerald Weinberg’s “The Psychology of Computer Programming”, which I strongly encourage everyone who works in or near development to read because it addresses most of the issues we think about when we think about programming on a daily basis - project planning, team structure, and blockers, with the additional mindblowing caveat that all of this was already discussed and written about in 1971.

The anecdote is about a developer, Bill, who was working on (ostensibly) a missile defense system, with instructions written in machine code. He got to a point where he thought he figured it out, but since you probably need a second set of eyes on a missile defense system, he asked Marilyn to review his code.

Code review was still in the nascent stages in those days, and Weinberg writes, “His value system, when it came to programming, dictated that secretive, possessive programming was bad and that open, shared programming was good. Errors that might be found in code he had written - not “his code” for the terminology was not used here - were simply facts to be exposed to investigation with an eye to future improvement, not attacks on his person. "

Marilyn found 17 bugs in the 13 lines of code. Instead of fuming, Bill’s reaction was to go around and tell everyone how impossible this code was, and how hilarious it was that she had found 17 bugs. While he was doing that, a few people joined in, for at this point, it was a game, and found a few more bugs. A scenario that could have ended with Bill accusing Marilyn of blocking him or of Bill hiding his code because he thought others would think he was a bad developer ended up much better because things were out in the open.

Good companies leave room for bugs and rough drafts. It doesn’t mean that work can be sloppy. On the contrary, the more people that check a piece of code (up to a certain number n where more code reviews actually start to be detrimental), the more error-proof the code becomes. Good teams, instead, leave the developer room for some slack. They know it’s going to take any developer, regardless of skill level, time to onboard, and that, ultimately, developers are humans with biases and different skill levels of code.

Teams that review each other’s code regularly level each other up. In the process, they also add safeguards: runbooks instead of manual entry, production systems with easy rollback, team members who are readily available to answer questions, good documentation, and they have people who go through onboarding contribute to the same process.

They also promote people who value all of these skills: patience, mentorship, and people who demand technical excellence while acknowledging what it takes to get there. Who you promote will tell your org chart how you want the organization to look, so it’s important to spotlight people who share these values and set the tone for the organization.

Repeated exposure to best practices

In the Middle Ages, the way that communities passed on best practices to future generations in the trades was through apprenticeships. If your parents wanted you to be a winemaker, around age 12, you’d pack your bags off and go live in a vineyard for several years (a tantalizing idea), where a seasoned winemaker would pay for your housing and lodging in return for you doing all the gruntwork that would eventually lead to you becoming skilled in your trade.

There is no apprenticeship for learning how to build Docker containers or dealing with prod outages. All we have at our own personal disposal are books (if they can keep up with how quickly tech changes) and internet resources which may or may not be correct, or out of date, or paywalled.

The antidote to this is being around just one good senior person who can give you at least a little of their time. Usually, this happens entirely by chance, and I wish I had a good recipe for how to make it happen for you specifically, but all of the very good people I’ve worked with, I’ve come across them entirely randomly in my career.

There is a way, though, to tell who those people are in your organization, and to try to work with them if at all possible. Good senior developers ask lots of questions to get to the root of problems, and usually they ask them publicly so others can find out the answer. Good senior developers figure out how complicated systems work. Good senior developers carefully review PRs and give feedback, and they also answer questions. It’s hard to define what a good developer does absolutely, but chances are you know who the good people in your organization are, because you’re always hearing about them, and because, if you have a question, they’re the first person you think about when going to for help.

Once you find them, find ways to be near them and absorb their knowledge. Listen when they talk, and watch how they review code. One great way to do this is to ask to tag-team on PR reviews. If you’re not at the point where you can do code reviews yet, help them write documentation. If you can take even one small thing off their plate, they’ll be grateful for your help next time.

If you, yourself are the good,senior person in this situation, be aware that being a good, senior person is a responsibility that is more than just writing good, correct code, although that in itself is a large, important responsibility. It’s also training other people to be as productive as you are.

The ability to learn

We’ve so far talked about the role of the organization, the team, and senior-level people in helping others to level up and become productive. What is our own role in bootstrapping our learning?

Learning how to ask the right questions at the right time is one of the fundamental skills of being a developer. Formulating the right question takes a lot of time, a lot of trial and effort, and a lot of tinkering with different solutions until the question even makes sense.

Especially as a junior, it can be very daunting to ask good questions. Something I realized recently is that one of the reasons senior people are good at asking questions is that they already know the shape of their expertise.

This is why an evnironment where it’s ok to ask stupid questions is important. One of the best ways I’ve seen of dealing with this is having a #dumbquestions channel on Slack. Another is having the Good Senior People ask seemingly simple questions in meetings to empower others.

Easy as 1,2,3

If it’s as easy as these three things, why don’t we do all of them every day? Why don’t we hire tons of junior people and train them up, why don’t we create places where people can learn, and why don’t we all teach people how to ask good questions?

The depressing answer is that all of these are completely invisible and almost not evident at all in the bottom line of any single given product or company, and it’s almost impossible to account for them since knowledge work is still impossible to measure productivity-wise. In most cases, they’re a nice-to-have. And, additionally, at the executive level, it can be very hard to tell teams that mentor and do internal training from ones that don’t based on internal process alone and reward the ones that are putting in the work, unless the good teams are also good at marketing themselves and ship good code just as quickly as they train.

However, I’m a firm believer that even starting to talk about things and giving them a name is the beginning of something, and so here I am sharing this, because I’m hopeful that more people will think about it as part of their daily workflows.