2021 Work Recap, or the conjoined triangles of success

Last year was an amazing year at work for me, easily one of the highlights of my career so far. I got to work more closely with Scala in both Scalding and Spark, learned PHP so I could deploy an website to millions of users, did a deep dive on recommender systems, broke and fixed Airflow, learned Flink, and generally worked really, really, hard. Quite honestly, 2021 is the hardest I’ve ever worked in my professional life, and I don’t particularly consider myself someone who shies away from grinding through stuff.

And, while I was working insanely hard, I was also having the time of my life. Every day, I context switched between four languages on average (PHP, Python, Scala, Java, and five if you count YAML), worked with live distributed ML systems in production and integrated them into web apps within the constraints of engineering best practices, and pushed PR after PR.. While I was doing all of this, I worked closely with dozens of extremely smart people who were also doing the same thing.

I have never been as intellectually exhausted, but I’ve also never been as happy and exhilarated by what I’ve been working on. Lately, there is never a time when I’m not thinking about problems at work, and the wildest part is that, to me, it doesn’t feel at all like work. It feels like I’m playing in my mind, trying to put together a jigsaw puzzle of different pieces that ends up being a functional machine learning system.

To me, it feels like I got The Disease. Feynman writes about this phenomenon in “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman”

“Well, Mr. Frankel, who started this program, began to suffer from the computer disease that anybody who works with computers now knows about. It’s a very serious disease and it interferes completely with the work. The trouble with computers is you play with them. They are so wonderful. You have these switches - if it’s an even number you do this, if it’s an odd number you do that - and pretty soon you can do more and more elaborate things if you are clever enough, on one machine.

After a while the whole system broke down. Frankel wasn’t paying any attention; he wasn’t supervising anybody. The system was going very, very slowly - while he was sitting in a room figuring out how to make one tabulator automatically print arc-tangent X, and then it would start and it would print columns and then bitsi, bitsi, bitsi, and calculate the arc-tangent automatically by integrating as it went along and make a whole table in one operation.

Absolutely useless. We had tables of arc-tangents. But if you’ve ever worked with computers, you understand the disease - the delight in being able to see how much you can do. But he got the disease for the first time, the poor fellow who invented the thing.”

Reading this made me wonder, what is it that creates job satisfaction? Is it purely the technical joy of being able to build something? Based on my own experience, I don’t think this is the case. I love building, but I can’t build in the absence of feedback - in order to be happy with what I’m building, I also need for there to be feedback from users and from product owners. And I also need to feel like I’m building something with other people. The technical piece is critical for me, but it cannot exist in isolation: some of my unhappiest work experiences were where I was working on extremely sexy technology, for weeks, alone.

As I’ve been moving towards the idea that there is no single thing that contributes to being happy as an engineer, it has to be a confluence of factors, I asked about this on Twitter, because surely I am not the first person who’s thought about this:

People responded with a lot of really good, thoughtful links and I encourage you to read all of them if you’re interested in what might make you happy at work. But, out of all the links, the ones that really stood out to me were Ryan’s link to Herzberg’s two-factor theory of job satisfaction and Jeremy’s writing about autonomy, purpose and mastery, from Drive by Daniel Pink.

The two-factor theory of job satisfaction briefly states that there are two groups of things that can motivate us at work, motivators like " challenging work, recognition for one’s achievement, responsibility, opportunity to do something meaningful, involvement in decision making, sense of importance to an organization", and hygiene factors that are not directly related to the work itself but are still necessary: salary, healthcare, work conditions, good pay, paid insurance, vacations. Aka, the HR meta around work.

What was interesting about the theory is that in several experiments, Herzberg found that people are unhappy if they don’t have hygiene factors at work, but that those factors are not enough to ensure happiness. People also need motivators as a layer on top of that work.

Drive goes deeper into ‘motivators’ and argue that people need to feel self-motivated at work through autonomy, purpose, and mastery: in other words, we need to feel like we’re working on something interesting, important, and that the work is being acknowledged: we need to feel like we’re not doing a Bullshit Job.

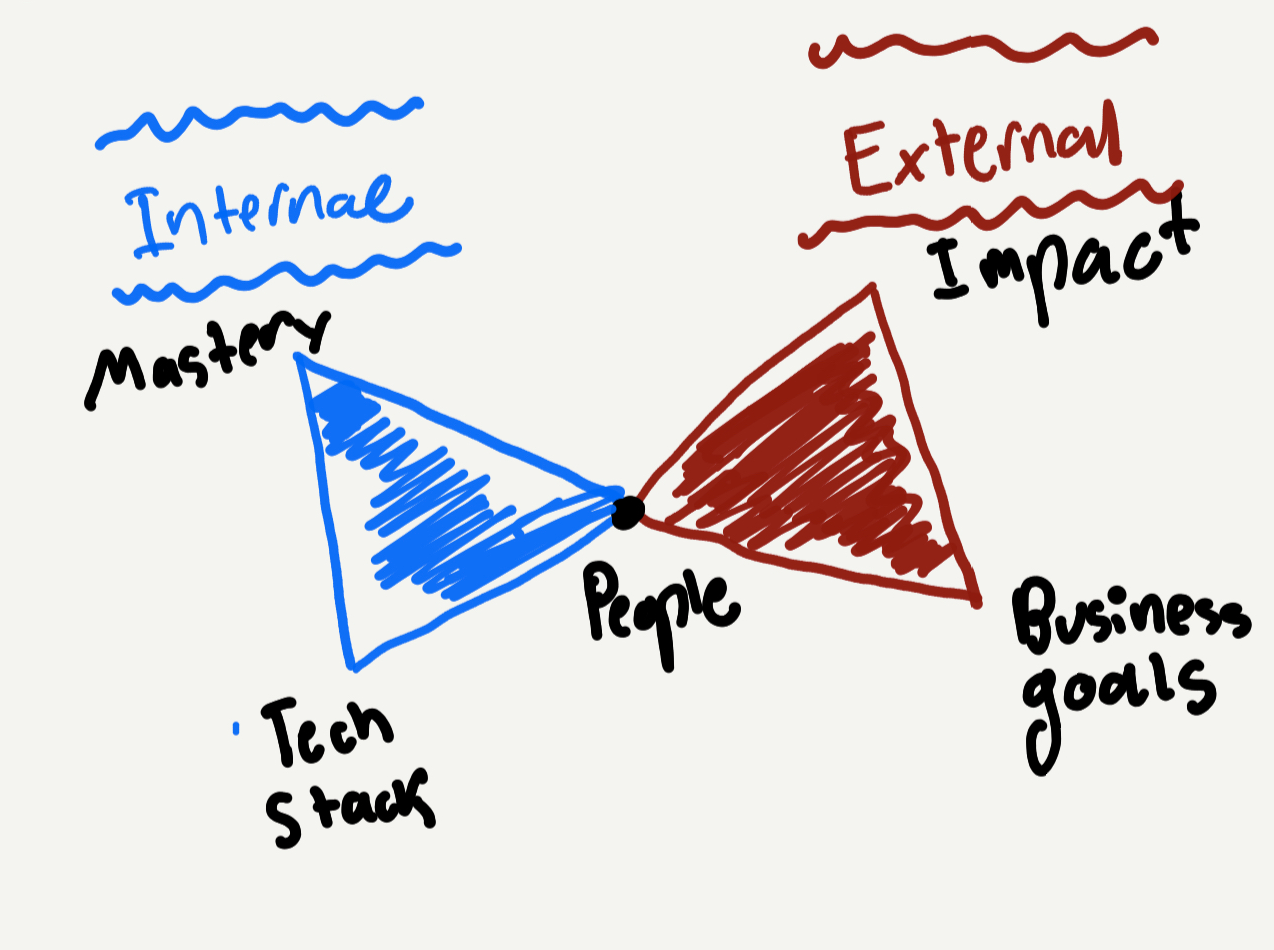

While both of these ideas are interesting on their own, it’s really the synthesis of both of them that led me to understand what it is that makes me personally happy: Intrinsic motivation is not enough, and extrinsic motivation is not enough. I need both of these in balance.

In order to feel successful, accomplished, and generally productive, I need the aspects that motivate me intrinsically: interesting work, the ability to choose it, the ability and time to learn, and a technical challenge. But, I also need the extrinsic piece: a compelling business case, working with people who also care about the product, people who believe short feedback loops and continuous collaboration are keys to levelling up technically and understanding what the business needs, who are also always thinking about ways we can work better or differently, and people who are willing to help..

Which brings us to my personal version of the conjoined triangles of success: (Harvard Business Review, let me know when you’re ready to license the bow tie)

And somehow I hit all of that last year. And that realization of what’s important and motivating to me in an engineering environment was just as valuable as all the technical things I learned.