We've been put in the vibe space

Jakob’s Law of UX goes something like this. I, as a user online, spend my time on many sites. As such, when I come to your site, I am already used to the way the other sites work, and I don’t want to learn new paradigms. Some also call these preconceived notions user mental models or affordances.

I like to call it the user-site contract.

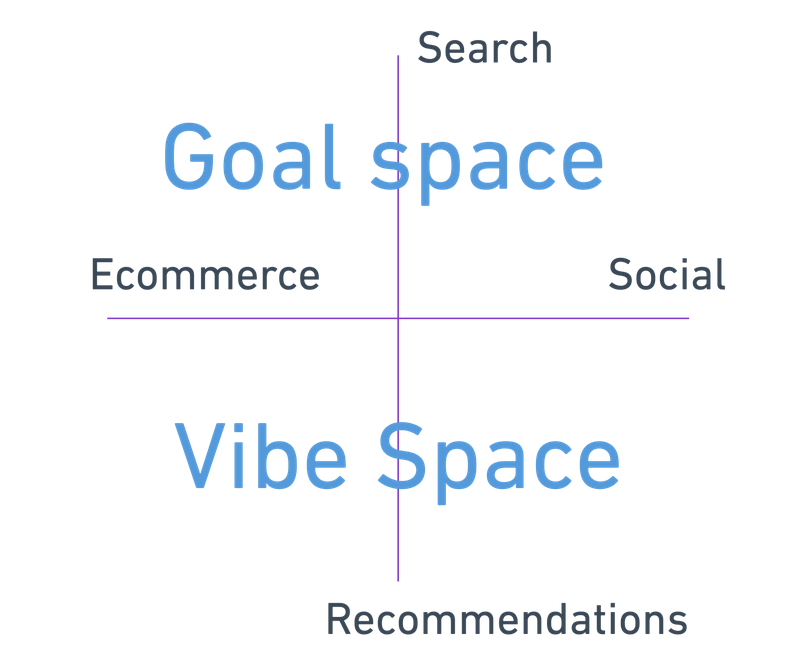

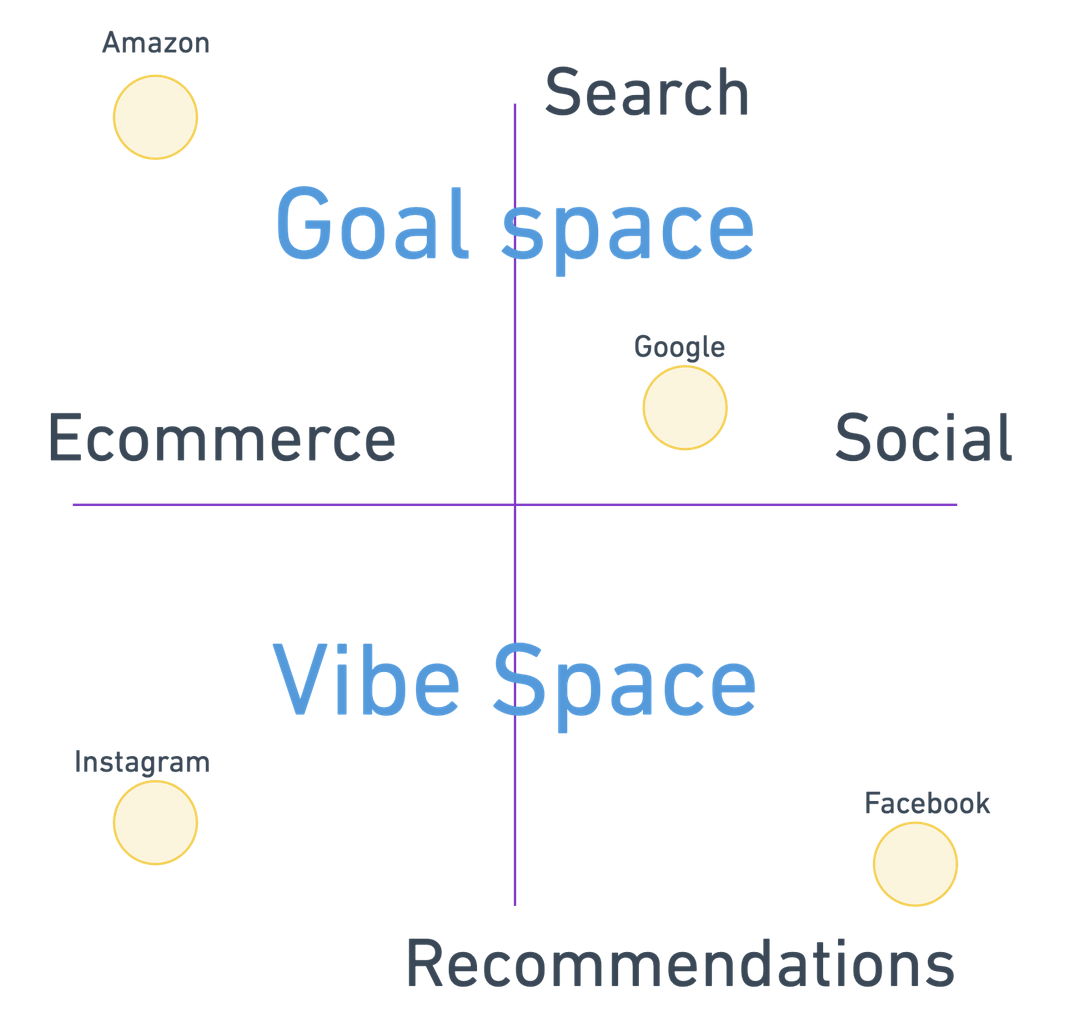

For years, we have been conditioned to navigate sites along several axes as content consumers: along search and recommendations, and along ecommerce and social.

Each of these four quadrants has their particular nuances, but we primarily understand what each is for.

On ecommerce search, we are conditioned to enter keywords stripped of context like monosyllabic cavepeople until we get what we want: “adidas sneakers white size 6 small.” Here, we are squarely in the goal space, and we are conducting mostly keyword search.

When we go to Twitter/Bluesky/Instagram/Discord/OpenTwang and we are served channel or post or image recommendations, we recognize that we are in the vibe space and can only influence these through our explicit and implicit behavior on a given site, which goes to some great matrix factorization in the sky and pulls out recommended items into a stream, or a timeline, or a carousel. We do this all publicly with the expectation that all our data is harvested and reintegrated into The Algorithm.

On social-type searches like Google, results are mixed because we perform hybrid search, a combination of keyword and semantic search that moves us closer to the vibe space: sometimes we want to search for “what minivan to buy”, sometimes “restaurants with mexican food and good music near me”, sometimes “tell me more about transformer models.”

On ecommerce recommendations, we are presented with items based on our browsing history, such as in our Instagram reels feeds, but we have no control over what those items are, other than we spent 10 seconds dwelling on a video of people drinking Chianti and get an ad for tickets to Rome.

For a long time, these four quadrants have been pretty distinct, because search and recommendations, while they occupy opposite ends of the same spectrum conceptually, have different tooling and architectures, and machine learning goals. You can even tell the way org structure of companies who hire for the teams have developed: usually there are distinct search and recommendations teams.

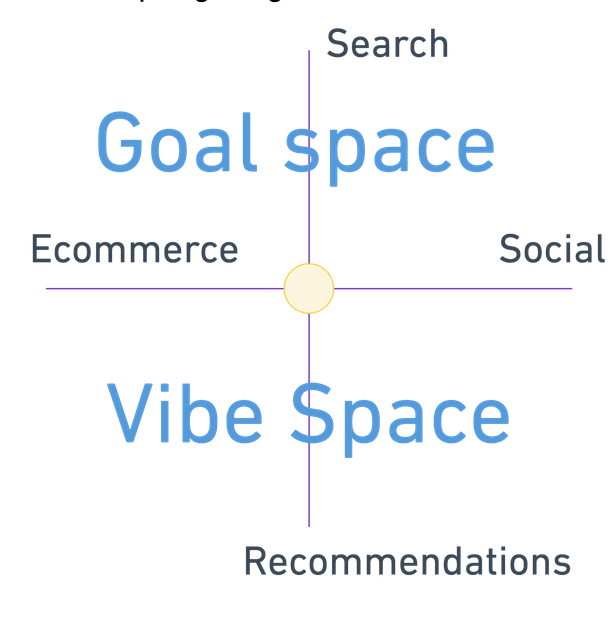

What happens in today’s world, when we have LLMs? We now have the collision of three different sets of user expectations.

First, we expect all LLM experiences to be like ChatGPT, because ChatGPT was the first LLM product to truly hit the market in a customer-facing way, and all products are in some way modeled on it. This cascades down even to the API, where many backend API products (VLLM, Ray, Llamafile), even if they don’t use the OpenAI API, are compliant with it; both the UX and dev-ex have become industry standard. The ChatGPT user experience is an open textbox that will allow you to get an answer about anything in freeform. We expect to be able to interact with this in natural language.

Second, we have our old expectation that search boxes are open-ended, but bounded by how we search: by keyword or short phrases, and that we will iterate on those short phrases to get what we need.

Third, we have our expectation that unclear results or results generated from semantic similarity or work in the latent space will be served to us as recommendations and tagged as such.

All of these are a clash of expectations that now need to be managed carefully, especially because, as I found in building semantic search products, it’s hard to guide customer intent in an open-ended solution space (i.e. what does it mean to search for a “vibe?”)

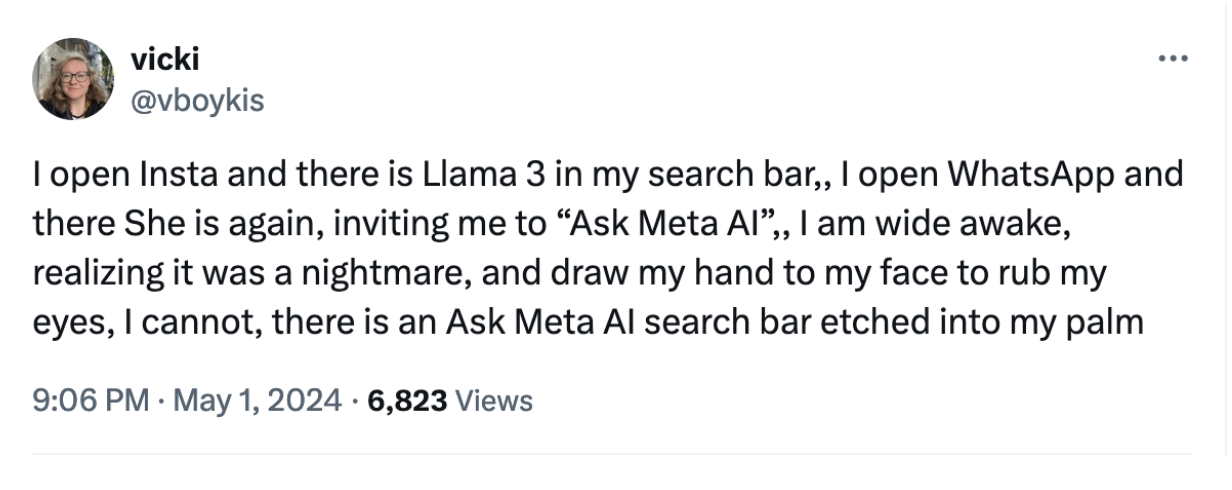

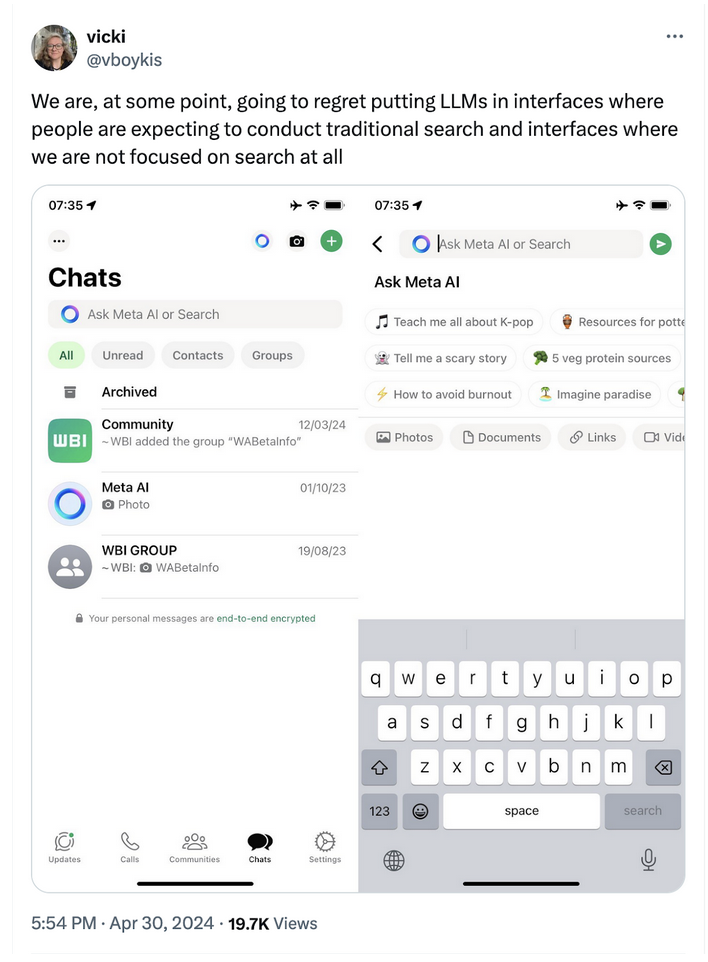

What then to make of Meta’s latest decision to put Llama3, a generative open-ended autoregressive model that can generate open-ended content, into every search bar in all of their platform properties?

These are four very hard design principles to square, because now, with open-ended models, we end up migrating all our use-cases to the center space.

Even when we open up Instagram search to perform a directed search, we’re greeted with The AI Box, which asks us to learn about K-pop.

But I don’t want to ask Meta AI about the best history podcasts or ask about k-pop, I want to find the video of the trained raven I saw a couple weeks ago. I want to perform social keyword search. And on Whatsapp, I want to talk to people on Whatsapp directly, without a chatbot in the middle.

I want to be in my four quadrants. And, because I’ve been conditioned by 15 years of past internet history to be in those quadrants, I’m annoyed by being pushed to the middle everywhere across all interfaces.

This is going to be a frustrating time for consumers until we get specific LLM use-cases sorted out and made less general. Interestingly enough, this is already happening to some extent in the enterprise space. It will be interesting to see what happens for us end-users and the contract. Until then, see you in the middle at the ✨.