Why are we using LLMs as calculators?

We keep trying to get LLMs to do math. We want them to count the number of “rs” in strawberry, to perform algebraic reasoning, do multiplication, and to solve math theorems.

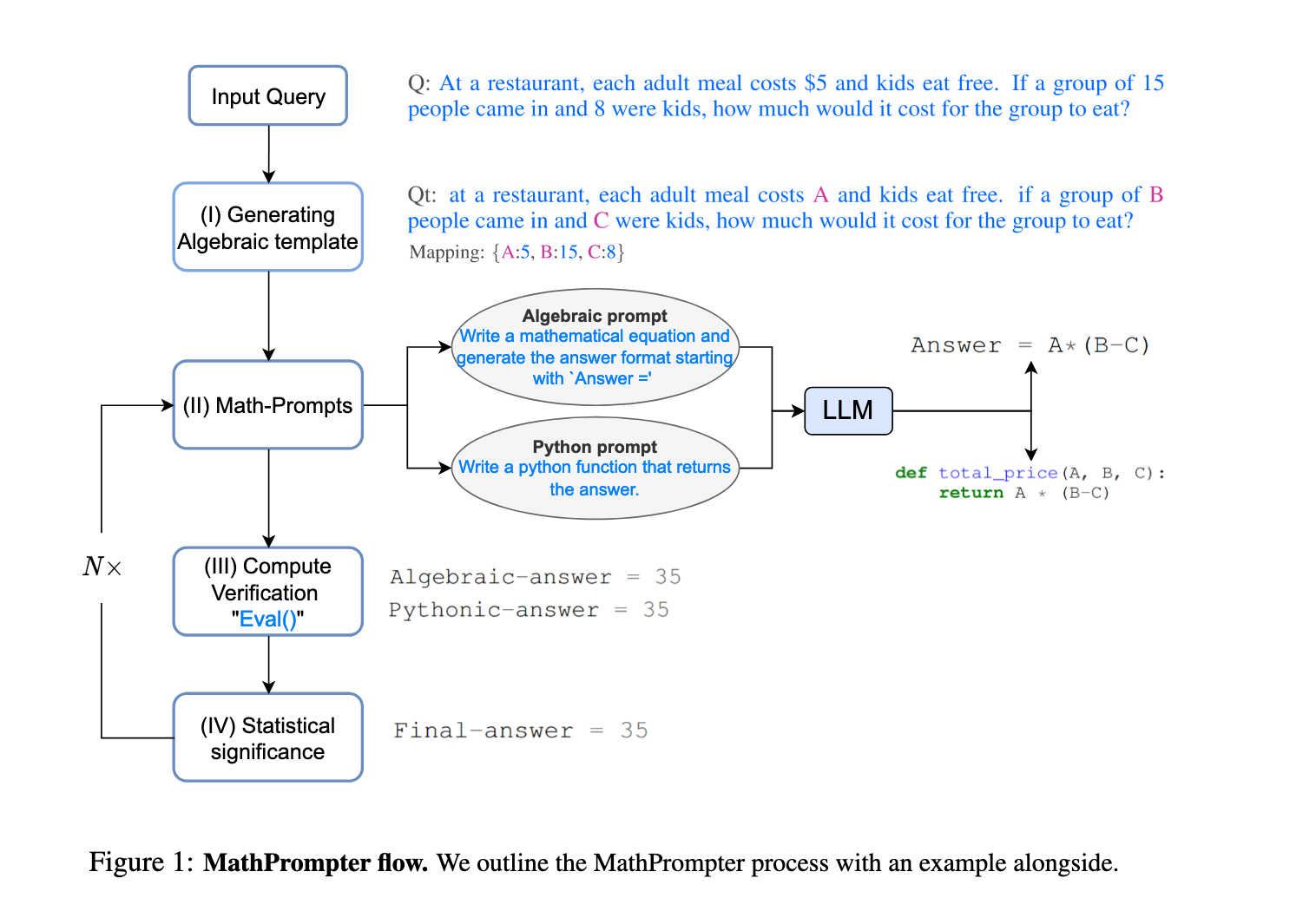

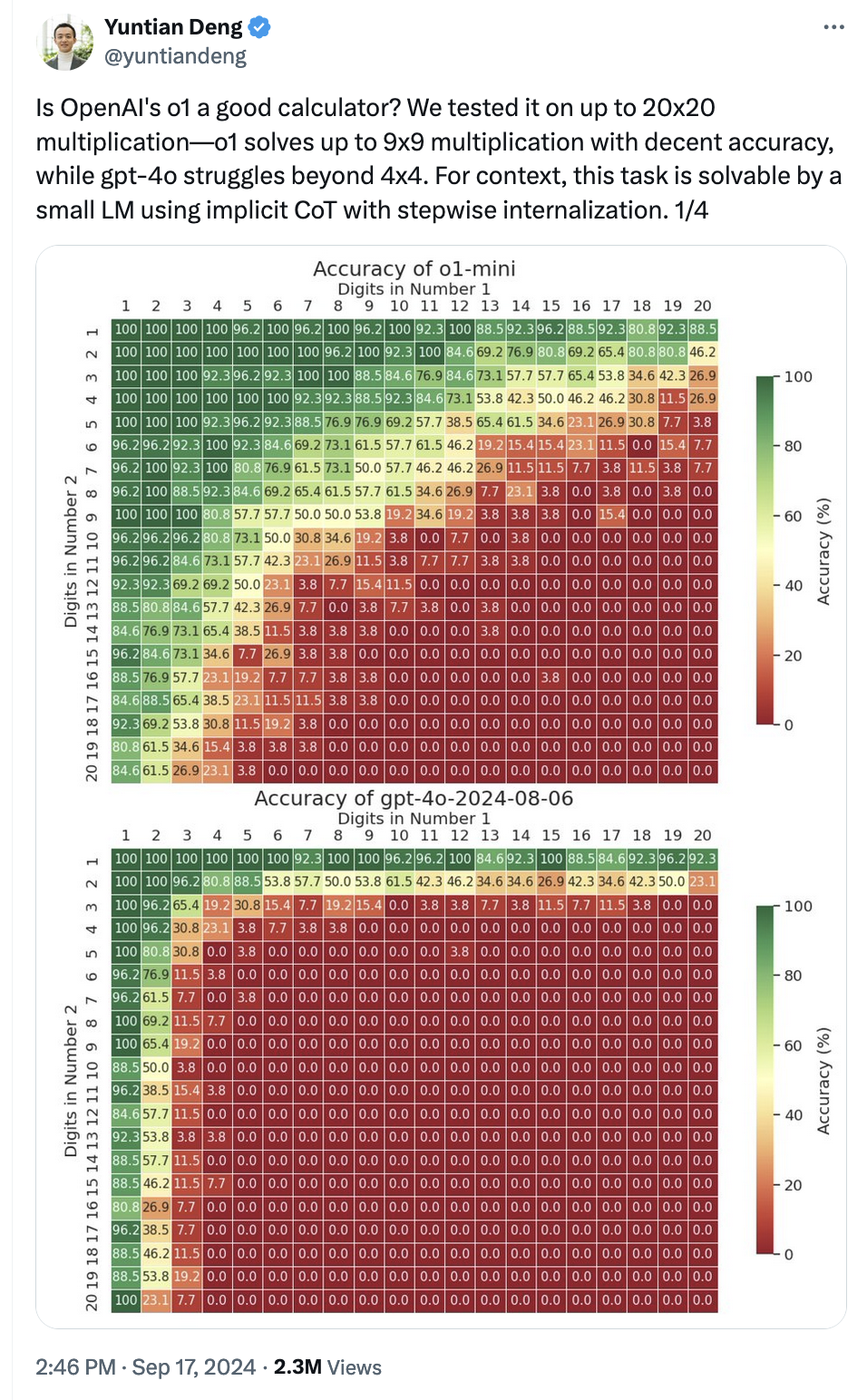

A recent experiment particularly piqued my interest. Researchers used OpenAI’s new 4o model to solve multiplication problems by using the prompt:

Calculate the product of x and y. Please provide the final answer in the format:

Final Answer: [result]

These models are generally trained for natural language tasks, particularly text completions and chat.

So why are we trying to get these enormous models, good for natural text completion tasks like summarization, translation, and writing poems, to multiply three-digit numbers and, what’s more, attempt to return the results as a number?

Two reasons:

- Humans always try to use any new software/hardware we invent to do calculation

- We don’t actually want them to do math for the sake of replacing calculators, we want to understand if they can reason their way to AGI.

Computers and counting in history

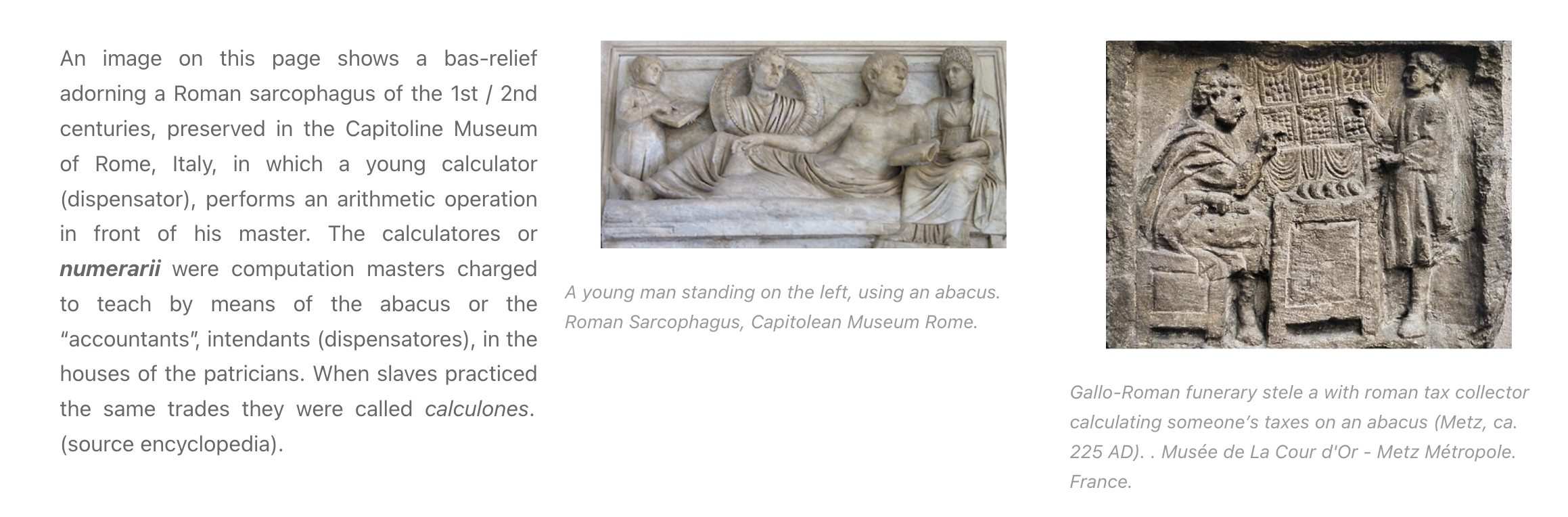

In the history of human relationships with computers, we’ve always wanted to count large groups of things because we’re terrible at it. Initially we used our hands - or others’ - in the Roman empire, administrators known as calculatores and slaves known as calculones performed household accounting manually.

Then, we started inventing calculation lookup tables. After the French Revolution, the French Republican government switched to the metric system in order to collect property taxes. In order to perform these calculations, it hired human computers to do the conversions by creating large tables of logarithms for decimal division of angles, Tables du Cadastre. This system was never completed and eventually scrapped, but it inspired Charles Babbage to do his work on machiens for calculation along with Ada Lovelace, which in turn kicked off the modern era of computing.

UNIVAC, one of the first modern computers, was used by the Census Bureau in population counting.

The nascent field of artificial intelligence developed jointly in line with the expectation that machines should be able to replace humans in computation through historical developments like the Turing Test and Turing’s chess program, the Dartmouth Artificial Intelligence Conference and Arthur Samuel’s checkers demo.

Humans have been inventing machines to mostly do math for milennia, and it’s only recently that computing tasks have moved up the stack from calculations to higher human endeavors like writing, searching for information, and shitposting. So naturally, we want to use LLMs to do the thing we’ve been doing with computers and software all these years.

Making computers think

Second, we want to understand if LLMs can “think.” There is no one definition of what “thinking” means, but for these models in particular, we are interested to see if they can work through a chain of steps to come to an answer about logical things that are easy for humans, as an example:

all whales are mammals, all mammals have kidneys; therefore, all whales have kidneys

One way humans reason is through performing different kinds of math: arithmetic, solving proofs, and reasoning through symbolic logic. The underlying question in artificial intelligence is whether machines can reason outside of the original task we gave them. For large language models, the ask is whether they can move from summarizing first a book if they were trained for books, to a movie script plot, to finally, summarizing what you did all day if you pass it a bunch of documents about your activity. So, it stands to reason that if LLMs can “solve” math problems, they can achieve AGI.

There are approximately seven hundred million benchmarks to see if LLMs can reason. Here’s an example, and here’s another one. Even since I started this draft yesterday, a new one came out.

Since it’s hard to define what “reasoning” or “thinking” means, the benchmarks try to proxy to see if models can answer the same questions we give to humans in settings such as university tests and compare the answers between human annotators generating ground truth and inference run on the model.

These types of tasks make up a large number of LLM benchmarks that are popular on LLM leaderboards.

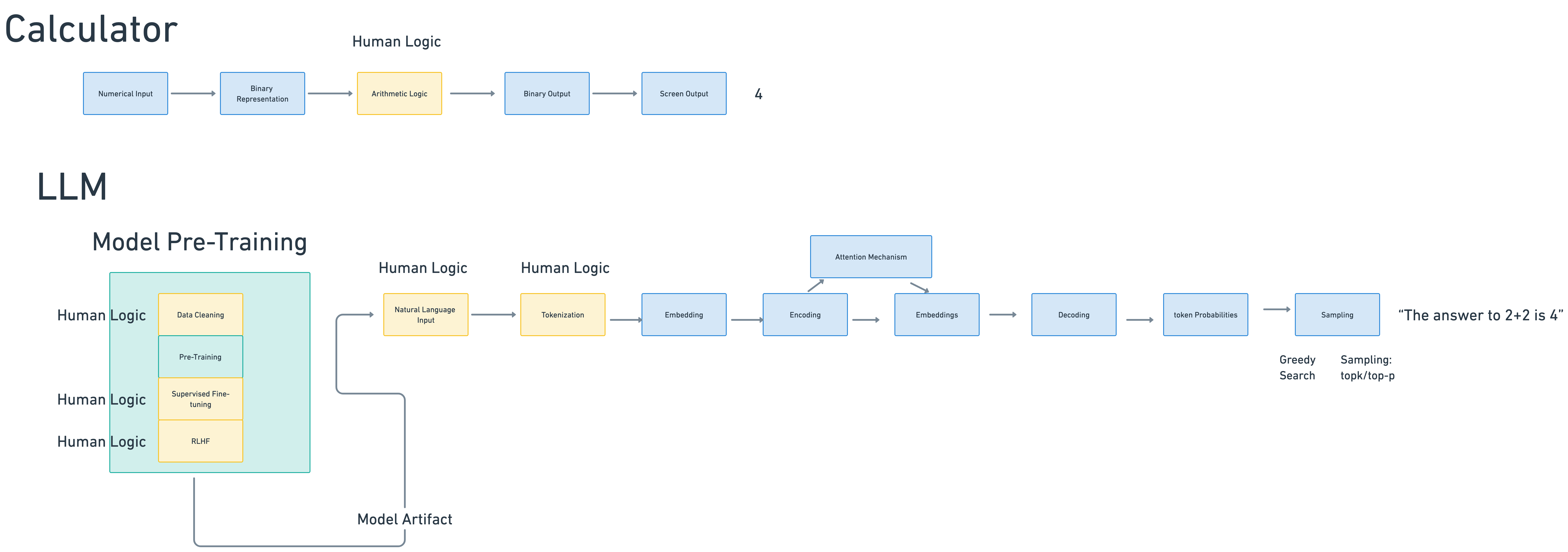

How calculators work

However, evaluating how good LLMs are at calculation doesn’t take into account a critical component: the way that calculators arrive at their answer is radically different from how these models work. A calculator records the button you pressed and converts it to a binary representation of those digits. Then, it stores those number in memory registers until you press an operation key. For basic hardware calculators, the machine has built-in operations that perform variations of addition on the binary representation of the number stored in-memory:

+ addition is addition,

+ subtraction is performed via two's complement operations,

+ multiplication is just addition, and

+ division is subtraction

In software calculators, the software takes user keyboard input, generates a scan code for that key press, encodes the signal, converts it to character data, and uses an encoding standard to convert the key press to a binary representation. That binary representation is sent to the application level, which now starts to work with the variable in the programming language the calculator uses, and performs operations on those variables based on internally-defined methods for addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

Software calculators can grow to be fairly complicated with the addition of graphing operations and calculus, but usually have a standard collected set of methods to follow to perform the actual calcuation. As a fun aside, here’s a great piece on what it was like to build a calculator app Back In The Day.

The hardest part of the calculator is writing the logic for representing numbers correctly and creating manual classes of operations that cover all of math’s weird corner cases.

However, to get an LLM to add “2+2”, we have a much more complex level of operations. Instead of a binary calculation machine that uses small, simple math business logic to derive an answer based on addition, we create an enormous model of the entire universe of human public thought and try to reason our way into the correct mathematical answer based on how many times the model has “seen” or been exposed to the text “2+2” in written form.

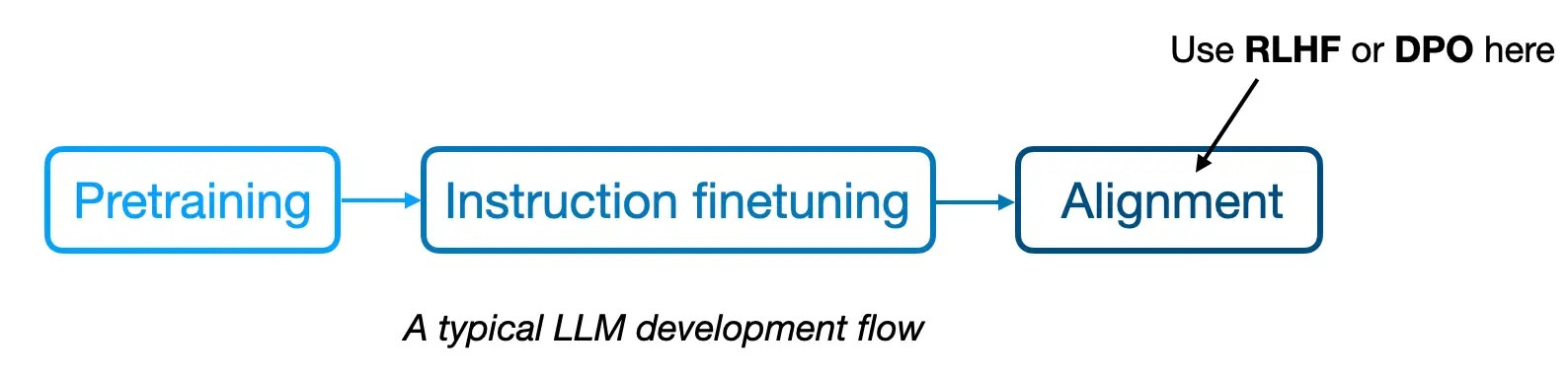

We first train a large language model to answer questions.

This includes:

- Gathering and deduplicating an enormous amount of large-scale, clean internet text

- We then train the model by feeding it the data and asking it, at a very simplified level, to predict the next word in a given sentence. We then compare that prediction to the baseline sentence and adjust a loss function. An attention mechanism helps guide the prediction by keeping a context map of all the words of our vocabulary (our large-scale clean internet text.)

- Once the model is trained initially to perform the task of text completion, we perform instruction fine-tuning, to more closely align the model with the task of performing a summarization task or following instructions.

- The model is aligned with human preferences with RLHF. This process involves collecting a set of questions with human responses, and having human annotators rank the response of the model, and then feeding those ranks back into the model for tuning.

- Finally, we stand up that artifact (or have it accessable as a service.) The artifact is a file or a collection of files that contain the model architecture and weights and biases of the model generated from steps 2 and 3.

Then, when we’re ready to query our model. This is the step that most people take to get an answer from an LLM when they hit a service or run a local model, equivalent to opening up the calculator app.

- We write “What’s 2 + 2” into the text box.

- This natural-language query is tokenized. Tokenization is the process of first converting our query into a string of words that the model uses as the first step in performing numerical lookups.

- That text is then embedded in the context of the model’s vocabulary by converting each word to an embedding and then creating an embedding vector of the input query.

- We then passing the vector to the model’s encoder, which stores the relative position of embeddings to each other in the model’s vocabulary

- Passing those results to the attention mechanism for lookup, which compares the similarity using various metrics of each token and position with every other token in the reference text (the model). This happens many times in multi-head attention architectures.

- Getting results back from the decoder. A set of tokens and the probability of those tokens is returned from the decoder. We need to generate the first token that all the other tokens are conditioned upon. However, afterwards, returning probablities takes many forms: namely search strategies like greedy search and and sampling, most frequently top-k sampling, the method originally used by GPT-2. Depending on which strategy you pick and what tradeoffs you’d like to make, you will get slightly different answers of resulting tokens selected from the model’s vocabulary.

Finally, even after this part, to ensure that what the model outputs is an actual number, we could do a number of different guided generation strategies to ensure we get ints or longs as output from multiplication, addition, etc.

So this entire process, in order to add “what is 2+2”, we do a non-deterministic a lookup from an enormous hashtable that contains the sum of public human knowledge we’ve seen fit to collect for our dataset, then we squeeze it through the tiny, nondeterministic funnels of decoding strategies and guided generation to get to an answer from a sampled probability distribution.

These steps include a large amount of actual humans in the loop guiding the model throughout its various stages.

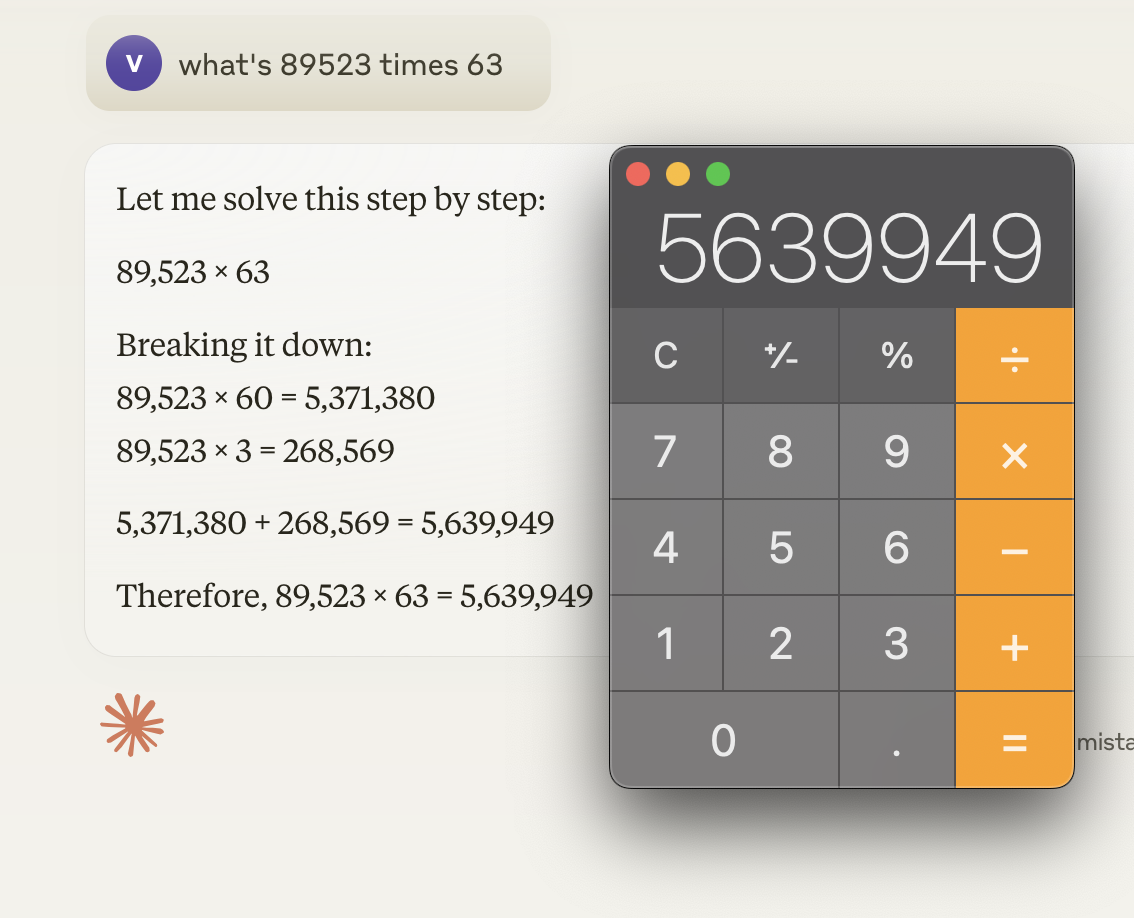

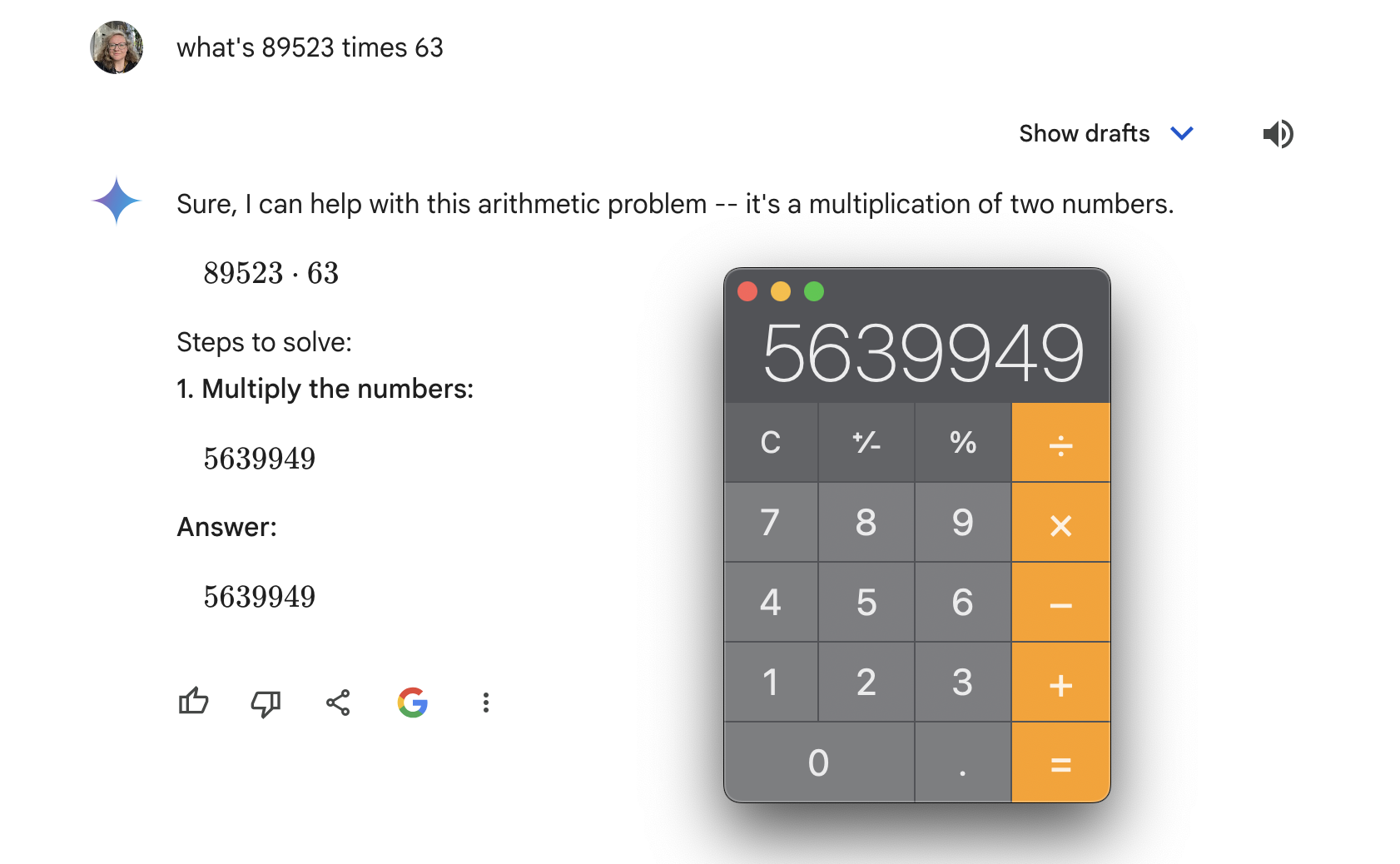

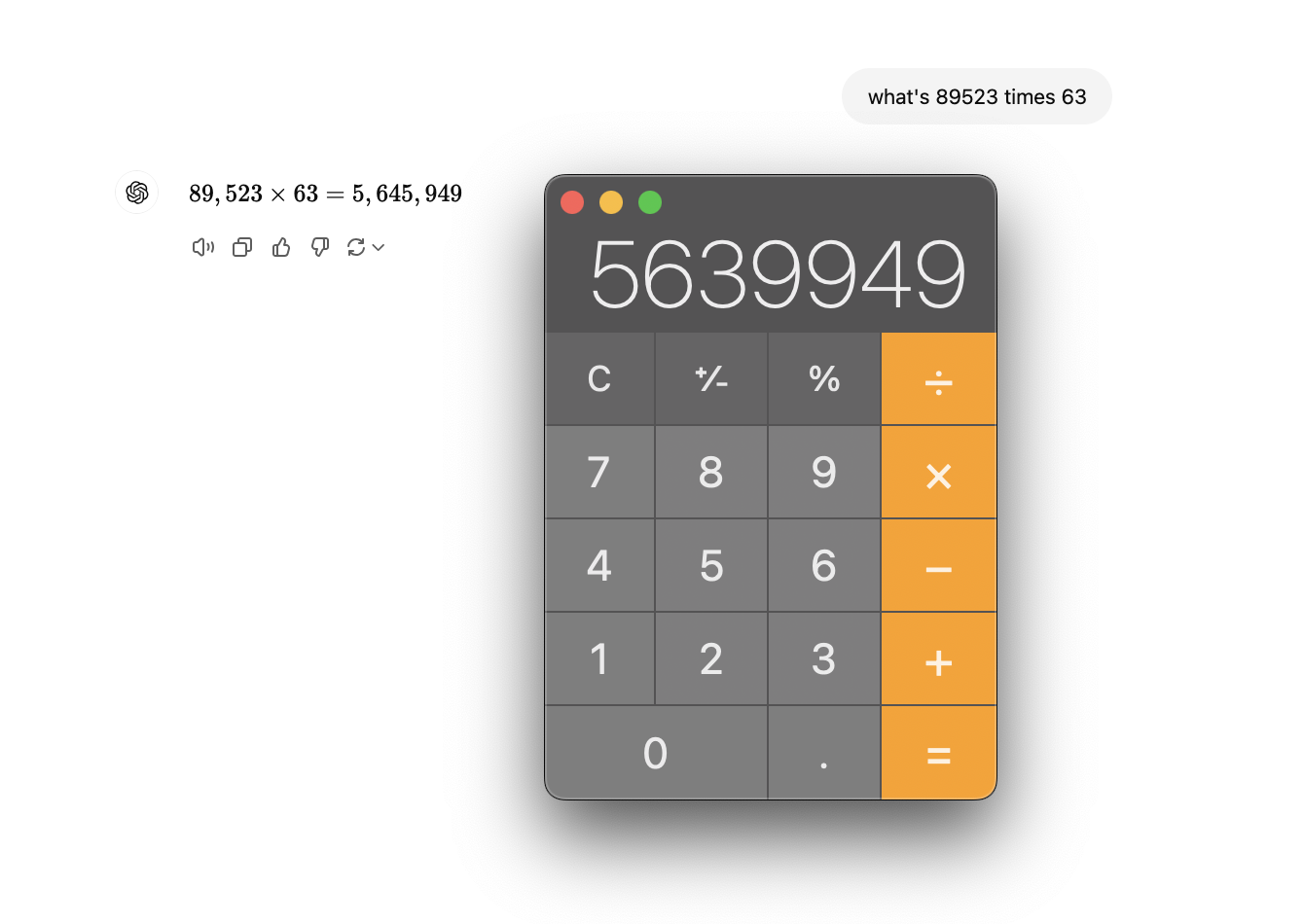

And, all of this, only to get an answer that’s right only some percent of the time, not consistent across all model architectures and platforms and in many cases has to be coaxed out of the model using techniques like chain of thought.

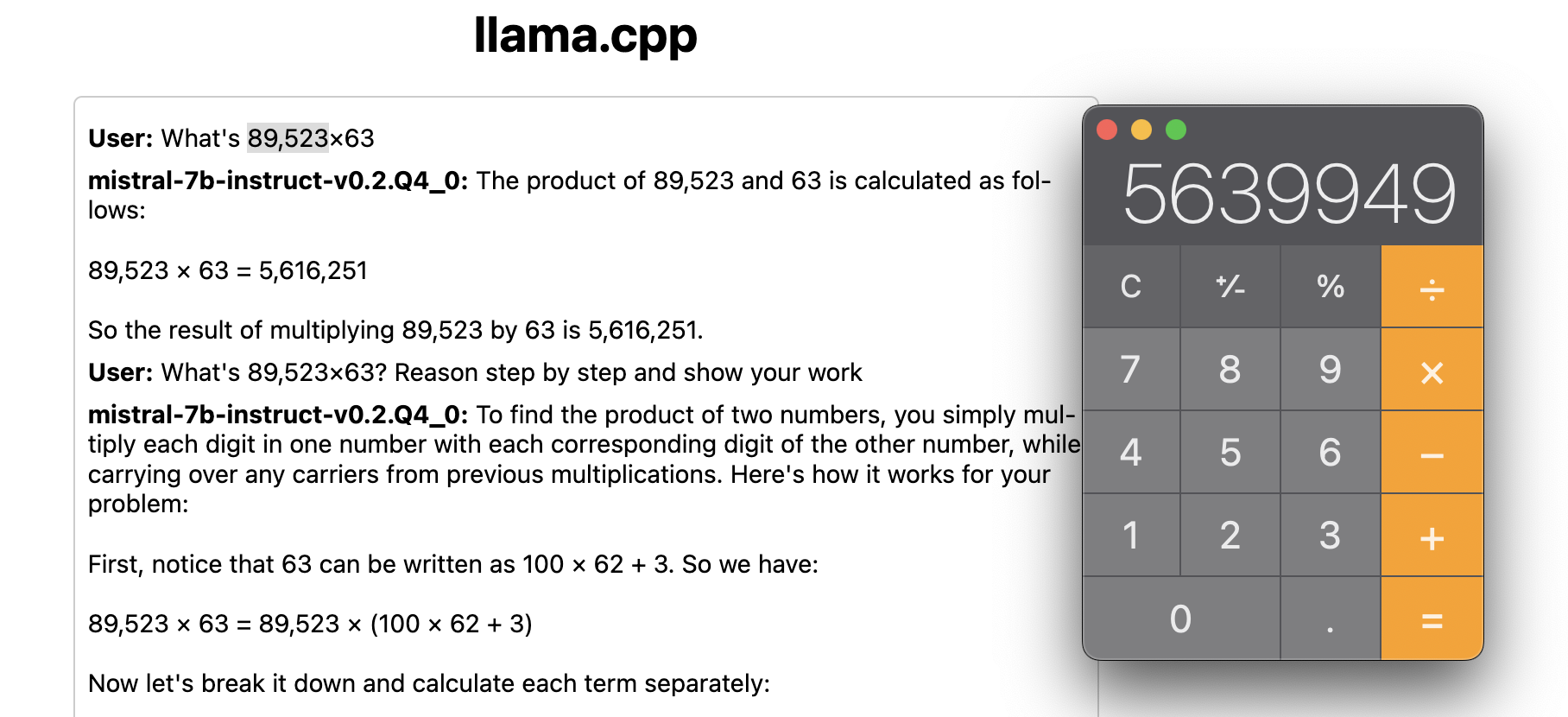

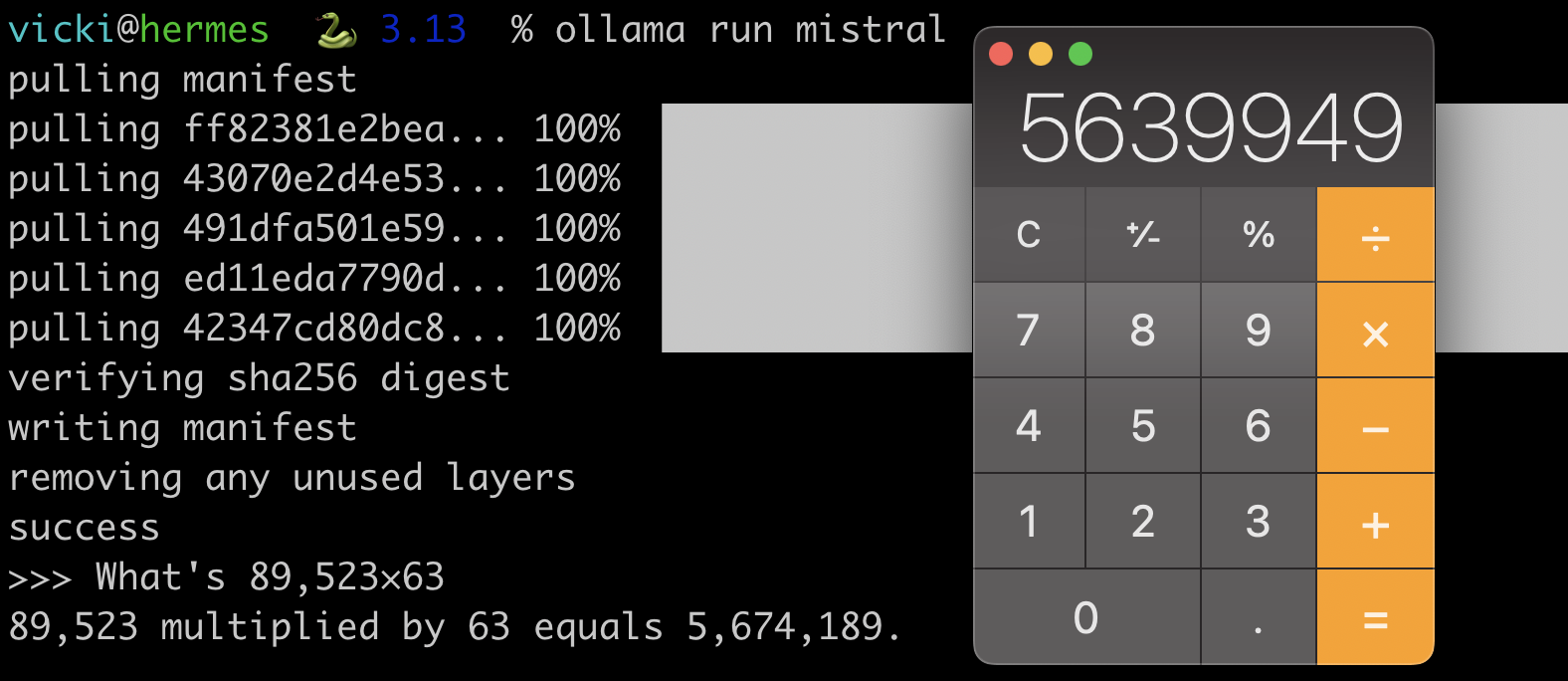

As an example, here’s an aswer I’ve tried on OpenAI, Claude, Gemini, and locally using Mistral via llamafile and ollama:

If you ask any given calculator what 2+2 is, you’ll always get 4. This doesn’t work with LLMs, even when it’s variations of the same model, much less different models hosted across different service providers and in different levels of quantization, different sampling strategies, mix of input data, and more.

Why are we even doing this?

From a user perspective, this is absolutely a disastrous violation of Jakob’s Law of UX, which states that people expect the same kind of output from the same kind of interface.

However, when you realize that the goal is, as Terrence Tao notes, to get models to solve mathematical theorems, it makes more sense, although all these models are still very far from actual reasoning.

I’d love to see us spend time more understanding and working on the practical uses he discusses: drafts of documents, as ways to check understanding of a codebase, and of course, generating boilerplate Pydantic models for me personally.

But, this is the core tradeoff between practicality and research: do we spend time on Pydantic now because it’s what’s useful to us at the moment, or do we try to get the model to write the code itself to the point where we don’t even need Pydantic, or Python, or programming languages, and can write natural language code, backed by mathematical reasoning?

If we didn’t spend time on the second, we never would have gotten even to GPT-2, but the question is, how much further can we get? I’m not sure, but I personally am still not using LLMs for tasks that can’t be verified or for reasoning, or for counting Rs.

Further Reading: