Table of Contents

- Flyover Country

- Welcome to Iceland. Here’s some Júníus Meyvant

- Iceland is for humans

- From lice to nice

- Small is weird. Small is good.

- Big is hard - for countries, and the internet, too

- Where to now?

- This is where I leave you

- Further Reading on Iceland

Flyover Country

When I was younger and my family finally made it to the American middle class, we went on vacations to Europe. Plane travel was a lot more boring in the days before cell phones, and I would spend a significant amount of any given flight tracking the progress of the tiny plane icon on the flickering screen. When Godthab, Greenland, and then the tiny dot labeled Reykjavik appeared on the legend, I knew we were close to our destination across the Atlantic.

For most traveling Americans, until very recently, Iceland was no more than a flyover destination. But the 2008 financial crisis, the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull, and the filming of Game of Thrones there, combined with aggressive marketing and low pricing by Iceland’s two airlines have drastically improved Iceland’s standing on the map.

Today, if you talk to any pour-over coffee drinker living within driving distance of an Ikea, there’s a seventy-six bajillion percent chance they’ve been. Since over 1.5 million tourists hit Iceland last year it really seems like everyone I know has either been, or is headed north.

In spite of all that, Iceland is still not a country Americans really pay attention to. I mean, we don’t care about most things that aren’t Kardashian, but Iceland, nestled way up against the Arctic Circle with a population smaller than Cleveland, can be easy to overlook. As such, I had no preconceived notions going in. But, almost immediately I was won over.

Welcome to Iceland. Here’s some Júníus Meyvant

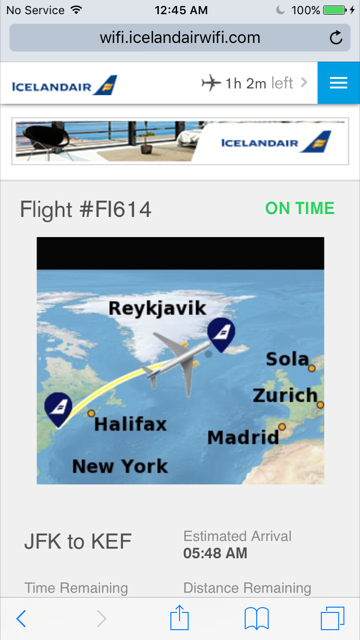

What amazed me the most was that there is a USB charging port right next to the TV screen of my Icelandair flight. I’ve flown an average amount, and nowhere yet have I seen this feature in economy class on American planes.

At first glance, this, seems like a totally banal yuppie thing to get excited about. But if you are flying with a smartphone, it’s a HUGE relief not to have to worry about charging in the airport where you land, saving battery, and generally running around like crazy on what should be your vacation or business trip. You just plug in, and you’re ready to go. It’s a really small thing that makes a huge difference in peace of mind for travelers.

As we boarded, Icelandair also played soft mood music from a Spotify playlist. To someone who is used to traveling within the American flight culture, where you’re lucky if the flight attendants throwing $14 bags of peanuts at you hit in the general vicinity of your torso, it was all very new. And, of course, you could track the flight path on your phone free of charge.

It so happened that we went to Iceland because Mr. B was invited to a bachelor party there. In my day, these parties were held at local dive bars where the floor was more Miller Lite than laminate, but that was before Instagram. I decided to tag along for a couple days before the party, because Iceland was so close, and because it’s been a while since I’ve travelled further than the distance between the crib and the couch.

We got in at six in the morning, but even in my red-eyed haze, I could see just how pristine everything at Keflavík Airport was. My freshly-charged phone immediately connected to Iceland’s Vodafone network without a glitch. “We’re here. Everything is clean and smells like Ikea,” I texted my mom.

I had already booked a ticket on Flybus, which goes from Keflavík to Reykjavik, online, so all we had to do was get on and wait. I’ve never been brave enough to take public transportation from the airport anywhere I’ve been, including even Israel, where I speak the language, but the website made it so easy. The bus, like the plane, had Wi-Fi, a feature we’d see being offered again and again on buses, in cafes, restaurants, and bookstores, like a lure to trap urban Americans wearing plaid button-downs.

Iceland is for humans

From the get-go, there were a lot of things in Iceland that seemed like they were out of a fairy tale about what an ideal human life should look like, at least from the perspective of someone living in the United States.

For example, on our first day, our guide from I Heart Reykjavik, took us on a walk through Reykjavik, stopping at a small building that looked like something out of Goldilocks and the Three Bears. “That’s the prime minister’s office,” she told us. “No guards, nothing. He just goes about his work here.” We walked on, towards another two-story building that looked like an office for a small-to-medium business.

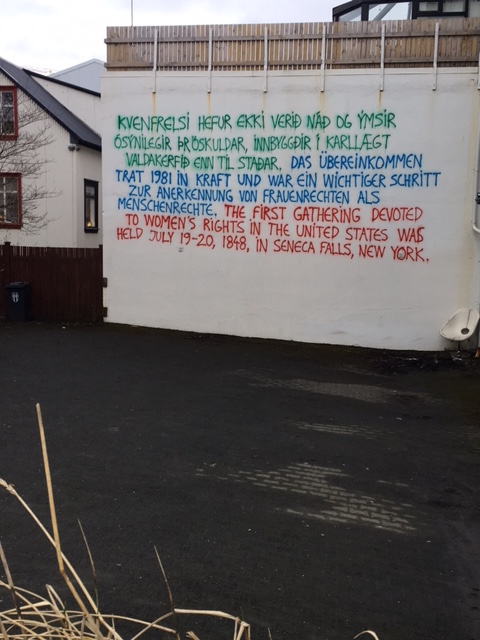

It was the national Parliament, the Alþingi. “It’s made up of 48% women,” our guide said. “We’re just short of 50%,” she continued ruefully. I have to admit, I had a sharp intake of breath. It sounded like an impossible miracle. But in Iceland, equality, and more importantly, humanity, shows itself in lots of different ways.

There is the USB charger so you don’t have to coddle your smartphone like an animal. In the big picture, there is gender equality. Not only do women make up a large percentage of the workforce, but childcare is heavily subsidized, costing something like $180 a month per child for eight hours of childcare, including food. Mr. B and I personally pay $800/month, and I know our daycare is on the cheaper end.

There is also a large social safety net, healthcare, and all the goodies that make Scandinavia – Scandinavia.

Additionally, I felt more like a treasured guest than a potential criminal when passing through Icelandic customs, more than I can say for my trip back to the country where I’m actually a citizen.

But there is a lot of humanity in the small things, too. For example, the tap water is not only potable, but delicious.

When we went to buy a bottle of water at the supermarket, the clerk looked at us like we were crazy. “You know it’s the same thing in the tap,” she said, motioning for us to put the bottle back. The shower water smells like sulfur, because all of Iceland gets its cold water from a glacier, and hot water from geothermal heating.

Then, there’s the matter of the prisons. The old town prison in Reykjavik, which had no wire fence around it, or even bars on the windows, grew too small (it can only house 16 prisoners) and is being reconsidered for repurpose as a cultural center. The current prison population of Iceland is 153, or less than one tenth of one percent of the population.

Oh, and everyone speaks nearly perfect English.

It seems very, very hard to find anything wrong with Iceland. Until you get to the financial crisis of 2008, when the three largest banks folded, the currency plummeted, and unparalleled levels of corruption were exposed in the government, leading to massive unemployment and genuine fear and panic.

But even as large and traumatic as that devastating moment of extremely poor judgement for the country, was, Iceland now seems to have passed it, if not with flying colors, at least with more wisdom and grace than the U.S. could muster up during its own fall. It’s true that the krona has fallen and Iceland experienced a brain drain after the crisis. But it’s also true that a restructuring of the economy has led to a significant decrease in unemployment. The bankers that caused the 2008 financial crisis are also in prison, where they “spend their days doing laundry, working out in the jailhouse gym, and browsing the Internet.” “Sometimes they go horseback riding,” our guide said.

The economy has been on the upswing since 2011, particularly with a lot of strength in the tourism sector, which the Icelandic government is heavily pushing - probably the reason all my friends have known about it. The low cost of the airfare to Iceland relative to Europe or even the West Coast in America, thanks to the hub and spoke model (Iceland is a huge place for flights from Europe and the United States to connect, thus maximizing capacity and optimizing costs for travelers), is huge.

From lice to nice

How did Iceland get to this point? Originally settled in the 10th century by Vikings (and any Irish slaves they picked up on the way), the island was not a very hospitable place. When the settlers first came, there were almost no native animal species, so they had to bring by boat all the livestock they could to survive. There were also few trees, meaning most houses were made of mud and turf. Life was simply miserable for the first thousand years of Iceland’s existence.

Also, the weather in Iceland is terrible. There are two seasons: rain, and lava. Exposed to both the Arctic wind and laid bare to all the vagaries of the Atlantic Ocean, it rains at least a little every day, in spurts. It was sunny for maybe 15 minutes that I was there. On a particularly windy day, we went riding on the small, sturdy horses that are descendants of the original horses the Vikings brought over (no imports are allowed to keep the purity of the breed), and all I could think about, instead of focusing on the beautiful, broody landscape of Hveragerði was about how many Vikings died of pneumonia and ear infections.

Things got marginally better over the centuries with more established trade routes, but as late as the the 1800s, men were climbing vertical cliffs plunging to the sea to steal sea bird eggs from ledges. Without these natural “pantries”, a large amount of Icelanders would likely have starved. If you weren’t killed by hunger, the climate, or random Turkish raiding parties, there were always the eagles, one of the only native bird species to grace the island.

The economy really kicked into gear when exposed to the economic crosswinds of World War II, and, of course the British and the Americans. Once the economy took off, it’s been going. Iceland is now diversified away from its original industries of aluminum production and fishing – although, thankfully, not too far. Some of the the best fresh fish I’ve ever had was in Reykjavik.

Small is weird. Small is good.

Looking at this vast narrative sweep of history as well as the grandness of its geography, you would think Iceland is immense. But, today, the population hovers around 330,000. The University of Michigan’s football stadium capacity is 110,000. As someone living in an enormous country, it’s hard to wrap my mind around a country I can wrap around, as Mr. B puts it.

Iceland is too small for a lot of things. In his book on Scandinavia, Michael Booth writes that Iceland is a country “where the talent pool is the equivalent size of Coventry’s [in England]… And if there is a limited number of doctors and teachers, that is also likely to be the case in terms of entrepreneurs, politicians, and economists…One cannot overemphasize, I think, how very, very few Icelanders there are. It is remarkable they have been able to build any kind of infrastructure at all. ‘Do they have heart surgeons, speech therapists, or yoga teachers?’ I wondered.’”

Coming from a country where there are not only yoga teachers, but yoga teachers for dogs, it is just impossible for me to imagine living in a country that gets by on the bare minimum. What if you have a rare medical condition (fly to Europe, it turns out)? Or your favorite salon is not open? How do people get online deliveries (pay through the nose for Amazon delivery, sometimes up to 100%, as Alda told me.)? What if you make a mistake at work - does everyone in the country know about it? That kind of closeness, particularly at the political level (which many say was a factor in the corruption due to the nepotistic, kleptocratic nature of the political relationships) fascinated me and terrified me.

But, because it is tiny and homogenous and scrappy, Iceland is successful in many meaningful ways. The president can give boys rides home from soccer practice, and he can welcome the country’s refugees at his house.

Dunbar’s number, stating that the number of close relationships a person can mentally keep in mind is about 150, works so well here, because the whole country is so small. Reykjavik can decide to limit traffic to large vehicles in the center of the city. Statistics Iceland can count the number of unemployed in the country on a single spreadsheet. Small social networks are good, because the level of trust between people is high, and easy to rely on.

Big is hard - for countries, and the internet, too

On the one hand, we have Iceland: a tiny country that’s managed to survive natural disasters, famine, banking collapse, and still manages to ooze human compassion and dignity. On the other, there is America, the Greatest Country in the World, where, just in the past couple months, we’ve had bloodied passengers dragged off flights, border patrol agents searching cell phones, innumerable protests, and Oreo Churros.

The answer is, I’ve realized, that it is hard to scale systems that are based on humans. To see this at work, you don’t have to look further than countries that have the most humans: China, India, Indonesia, and Russia, none of which are particularly stellar examples of human rights, quality of life, or openness of society. It is obviously very hard to do an apples-to-apples comparison of each country, but numerous studies have shown that it is immensely impossible to synthesize vastly differing opinions and viewpoints. How can you create a policy that makes sense for both an elderly South Asian immigrant retiree in California and a head-of-household lower-middle-class factory worker in Michigan? Multiply that question by one million, and then by three hundred again. Assuming you’re even creating these policies in good faith to begin with, and not essentially using the vitals of a person’s life, such as immigration status, for example, as a political weapon.

I’m not the first person to come to this conclusion, that the human mind cannot grasp all the moving pieces of humanity. Alesina points out that “[G]reek philosophers emphasized the benefits of small and homogeneous polities. Plato calculated the optimal size of a polity down to the precise number of households, namely 5,040 heads of families.” (The Greeks must have also gone to Iceland to take selfies and write thinkpieces.)

I think this concept is also extremely obvious in today’s internet, which is essentially an uber-republic based on the movement of human thought. In an essay from back when he used to actually write, Paul Graham says that it’s important, when you’re starting a company, to do things that don’t scale Many companies (in this case, laundry start-ups) took this to heart, and did things like sent cookies to their customers.

“they sourced cookies from bakeries in their three markets—snickerdoodles in San Francisco, frosted red velvet in L.A., classic chocolate chip in Washington, D.C.—which the ninja delivered, wrapped, along with the freshly laundered clothing. "

As these companies became larger and larger, pressured by investors to explode with growth, and news users, it simply became untenable to continue this. If you are a startup that’s nationwide, you have to coordinate fresh cookie delivery for 10, maybe more, major metro market. You start to lose track of your clients, and you break Dunbar’s number. You simply stop doing things that are small and handmade.

Etsy is now having this same problem. The site originally started as a way for arts and crafts vendors to sell cool, handmade stuff to people on the internet. I was one of those people and for years enthusiastically bought stuff. And tons of people I know buy stuff on Etsy. Some are even sellers and have made pretty decent money on it. But recently, Etsy announced that it was “letting go” of its CEO and laying off close to 10% of its employees.

Why? Because now that Etsy is so successful, there are tons of fakes on it, coming from China. It’s very hard to detect these. This thread offers lots of people trying to solve the business problem, but in the end, they all agree that it is hard to offer genuine artisan stuff to hundreds of thousands of people. The best stuff is unique and stuff that there are few copies of, stuff that you buy at a craft fair or commission a friend to do. Authenticity, like most good human endeavors, it turns out, does not scale.

And how about Facebook? It boasts a ton of users, over a billion of them in fact, but now, as we see, is having enormous problems getting all of these users to have quality conversations, no matter how hard it tries to wrangle them with algorithms.

In my experience, this is true for all online networks. In the beginning, most online communities established with the goal of talking to other people and sharing information, are small and good, like Iceland. Users know each other, trust each other, can communicate. Sure, it can be a little boring, just like Scandinavia, where everything works so well because everyone is from the same cultural background and shares the same values.

Then, if the forum or community is really good, something called eternal September happens. Eternal September means a lot of new people who don’t know the context and rules of the community come flooding in and overwhelm the community norms. I’ve seen this with every single good message board I’ve been part of: my pregnancy message board, Facebook when it was just for people I knew in college, and Twitter. I learned so much from these communities, but as soon as people found out they were good, and were are opened up to an intimately large amount of people, the community feel left, immediately, and got swallowed up by the noise of the internet.

All of these platforms are meant for connecting a large amount of different kind of people, but their approach is the same as for everyone: measure some small sub-sample, create an algorithm rule for behavior based off that, and funnel everyone through. That’s how you get things like racist chatbots, livestreamed murders, and general feelings of animosity and hatred to what is supposed to be a way for people to connect and share what it means to be human.

The problem is, these kinds of automatic approaches only work with machinery. Machines can do the same thing over and over again without variation. Humans are weird and sensitive and unique and have unique social and cultural quirks, which is why their behavior can’t be predicted or controlled by science. The whole field of economics, for example, is based on the assumption that actors are rational, which is why economists didn’t see the aforementioned 2008 financial crisis coming.

That’s how it is with companies, countries, and all human endeavors threaded together with networks sewn by human thoughts. There is a moment when the thing, whatever it is, is too small. Then, there is a sweet spot where the thing, whatever is, just works. Then math and human nature take over and tip it over the scales to something that is too hard and crazy to manage.

Where to now?

I don’t claim to have all the answers, or any of them, really. I’m not a sociologist, an economist, a public policy maker. I’m just some random person on the internet reading free Harvard papers and linking to them to look like I know what I’m talking about.

The kneejerk, disturbing conclusion from all of this for both social networks and countries is that they should be kept small and homogenous, which is kind of the point of the dangerous wave of populism sweeping the United States and parts of Europe right now.

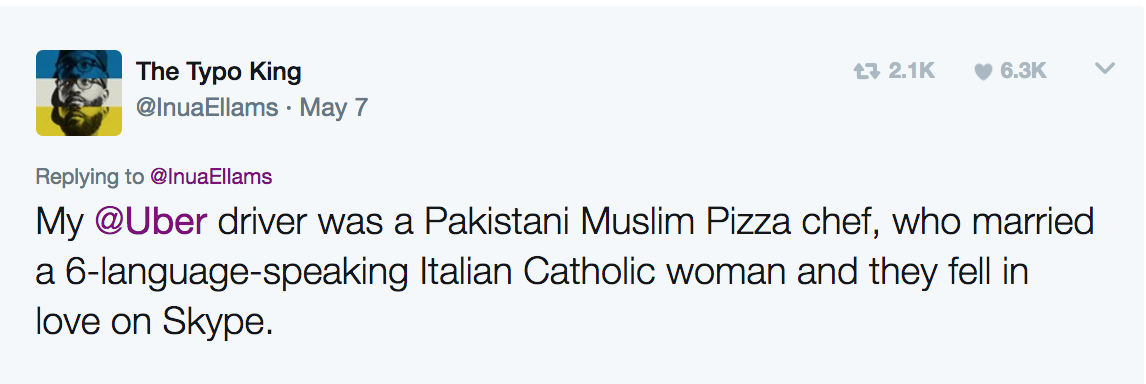

But that’s absolutely not the right answer, because there are a lot of beautiful things to gain from heterogeneity. For example, when you do the internet correctly, things like this happen:

And when you do the United States correctly, things like my family happen. My family, living in misery and poverty in the Soviet Union, immigrated, worked their asses off for years, sent me to school, sent me to college, and now has a granddaughter who is completely American, yet is learning Russian as her first language. You get the beauty of differences, something new and beautiful, just as beautiful as the Icelanders’ valiant effort to preserve their own language and culture, but in a completely different way.

But the problem again, is that neither of these things scale. So, small is good but doesn’t scale and can be overwhelmed by changes, and big is powerful, but ugly.

What do we do? How do we create more of these types of positive experiences, more positive political outcomes, that make us feel ok instead of opening Twitter again and grinding our teeth? (As a side note, once I visited Iceland and saw how nice it was, I realized I had actually been physically grinding my teeth for four months in a row.)

I think the answer is probably really complicated. And it’s an issue that we are all collectively, myself included, just starting to seriously think about, so it will be a while before any real solutions that are not 4500-word placeholders for beautiful pictures of Iceland start to crystallize.

I mean, it’s not like we can say, ok, let’s split up the 50 states into sovereign nations and we’re all cool now. (Actually, I think some guys tried this once and it didn’t work out too well, from what I heard.) We also can’t mandate the Transatlantic accent and a copy of Born in the USA for everyone that gets off the plane. We can’t make our healthcare system more modular, and we can’t really stop the national news from making us freaked out about remote things that have no impact on our daily life.

But a good place to start in the United States is - and I hate to sound like a public radio host from the 1990s - to care about local stuff. We have to act, first, within our own communities, in a pretty manual way in order to rebuild the connections we broke while growing. We need to better understand our neighbors. We as real citizens should be doing more local things: reading and supporting local news, trying to see what local problems are politically, and generally trying to understand the people close to us. For an introvert like me, this prospect is terrifying. But, I am embarrassed to say that, while I know what some guy in a newsroom in New York thinks about what’s going on in Russia, I have no clue what the names of all the people on my street are.

Online, we need to make the big feel smaller, in the right ways. The challenge to start small from something that is currently controlled by Facebook and Google, is very hard. But people are doing it. Look at The Correspondent, or Open Culture, or Brain Pickings, or thousands of other small projects that have good communities around them. We need more of those, and we need people to fund them, and for them to be built with communication in mind from the ground up.

In our Facebook groups and our K-holes, we need to build good communities with the tools we already have by being decent human beings, cutting down on the outrage, and learning how to be both contributors and moderators. Because we need moderators. Lots and lots of moderators. Moderators are people in active commenting communities who read comments, filter out the ones that violate community rules, and generally keep everyone in line.

Moderating is a hard, thankless task that can often even result in psychological harm. Which is why we need systems and tools that, instead of funneling human behavior, support and empower moderators, editors, and anyone who has to interface with people online.

I think companies have started to realize this: Facebook is hiring human moderators to clean up the flotsam of human content that people leave behind, but it remains to be seen whether they will be treated as important parts of the Facebook ecosystem, or disposable first-responders.

This is where I leave you

Cycles of growth and reduction are only human nature. We are constantly caught between the two extreme limits of our ambition and our unconquerable Dunbar number. Humanity has had eras of exploration and joy, and eras of war, plunder, and the Taco Bell Fried Chicken Taco Shell). The good news is that I think we are (I hope) not back at the Dark Ages yet, even if Kardashians is still on the air.

I am usually extremely grateful to come back to America. When Mr. B and came back from Israel, a country I truly and deeply love with all of my heart, I almost cried listening to the Stars and Stripes play on tv as we ate in a Wendy’s. This time, seeing the American flag, I was hit with more of an undertone of garishness. In other words, coming back from Iceland, I’m finally seeing America as the rest of the world sees it - big, brash, unreasonable.

But last week, I left my keys in the door (again), and a woman in my small town rang our ball, put my keys in my hand, and said, with a smile, that I should be more careful next time. Which is also America. America with a lower-case a - a small a. And it’s with a lower-case a that we should start, online, in person, and anywhere where humans live and think.

Further Reading on Iceland

This list is by no means exhaustive, but if you’re interested, should give you a good gateway into the culture and history.

Grapevine.is is a great English-language paper and magazine

Iceland Review Meatier essays, in-depth.

Alda Sigmundsdottir writes a bunch of excellent, well-designed, and cute books that are short, but really dense and full of funny essays on Iceland. My favorite was probably The Little Book of Icelandic.

The Almost Nearly Perfect People by Michael Booth is a fantastic book about Scandinavia, analyzing its social and political systems, as well as how they got there historically, with a huge sense of humor

If you don’t do anything else, please listen to this beautiful-creepy rima,Haustið nálgast, about the onset of autumn.