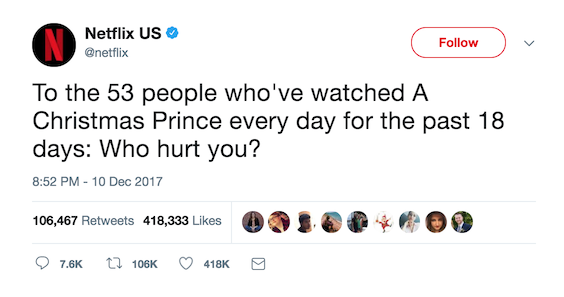

Earlier this week, Netflix tweeted out a seemingly-innocuous throw-away joke about how comforting it is to watch terrible Lifetime-like movies.

The tweet immediately went viral, but not for the reason Netflix probably imagined. In the process of Brand Building, the company ultimately revealed that it was not above exposing proprietary customer viewing data to hundreds of thousands of people on Twitter for quick laughs.

There is a small caveat: having worked previously with streaming viewing data, I’m not entirely convinced the data in the tweet was real. It’s very likely that this was either someone re-starting a stream erroring out several times, or cats/kids playing with the remote. Or, perhaps the movie showed up on the person’s recently-viewed navigation menu and them selecting it through error. Or, simply, the team behind the Twitter account could have made the stat up.

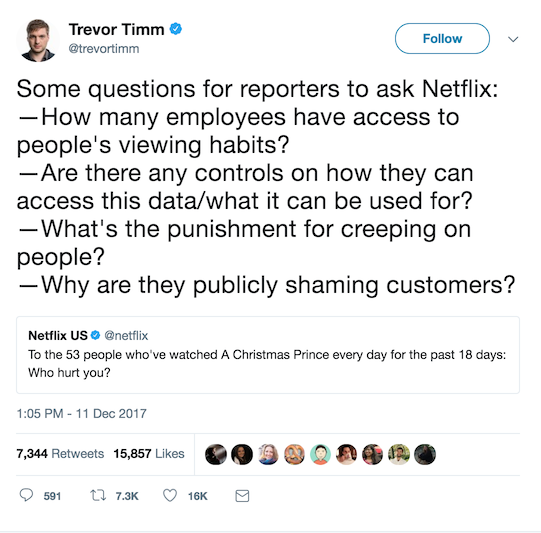

Regardless of the truth, the way it came across to the public was that someone, somewhere, had run a SQL query and come up with a small, potentially uniquely-identifiable data set of viewing habits. The internet immediately became angry, and a lot of prominent tech journalists started calling Netflix out.

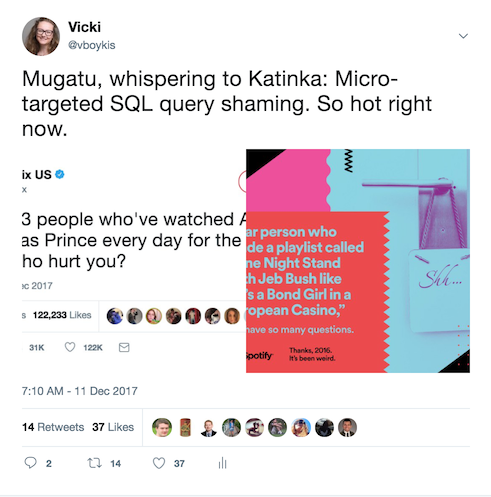

Unfortunately for anyone familiar with data, this isn’t anything new. Spotify did something similar last year.

However, these two examples are some of the most benign user information companies currently collect from consumers. From Facebook, to companies that collect credit scores, healthcare history, viewing habits, browsing habits, and purchasing habits, and finally, ending with the government, which collects and aggregates this data to determine whether citizens are a threat to America, data collection is constant, merciless, and not optional for consumers.

Not all data collection is bad. Companies genuinely do need to collect data to improve customer experience, and to understand how their business is doing. Cities need to understand their citizens. Cancer researchers need to understand whether patients are getting better.

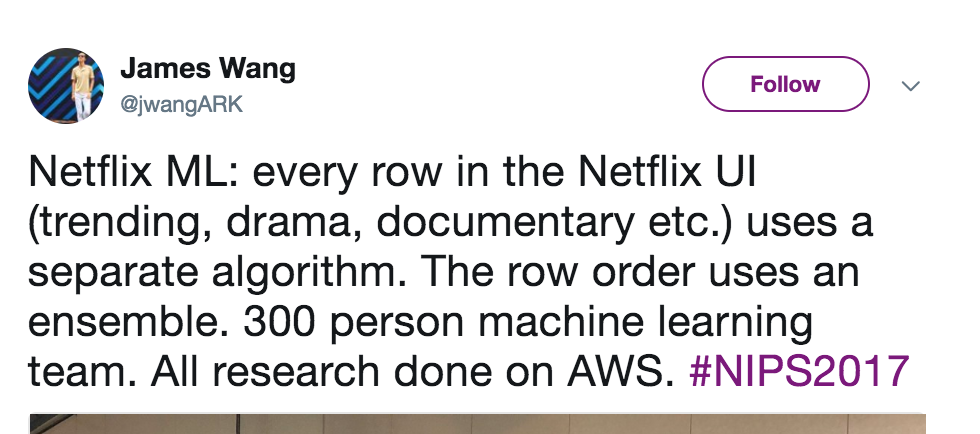

However, it’s becoming increasingly hard to differentiate necessary from “We can do this just because we have it,” which is the territory Netflix seems to have wandered into. For example, in a booth at NIPS, an increasingly-popular artificial intelligence and deep learning conference a couple weeks ago, Netflix mentioned that they had a team of 300 ML experts and data scientists essentially creating an algorithm for each separate row of recommendations. Given that the recommendations are, frankly, not that great, is it really necessary?

All of this is a debate data people have been having for at least the last five years. Many rolled their eyes at the tweet: this was nothing new, especially with the latest trend in the media to suddenly become critical of large internet-centric companies.

But, for me, the tweet was an amazing present. Most of the people in my life don’t know anything about this debate. They don’t know about how logging streaming data works, about how logs are cleaned up and processed in Spark or Splunk or Kafka and put into SQL warehouses for different departments to access, how those departments access them and share the data, email data, send Excel files full of data to other departments. They don’t know that what happens when they see The Christmas Prince in the media is that some Senior Vice President of Strategy somewhere decides, sometime, that we need a funny tweet about The Christmas Prince because it’s trending, and how there is a mad scramble from some analysts to pull together some statistics, any statistics on The Christmas Prince. They don’t know that these analysts probably have access to everything everyone’s ever watched and can use it to look up the viewing habits of their friends and family if they want.

None of them understand what data collection really means, not just at Netflix, but at Facebook, at every location you pass by as your phone silently checks you in, every email you send, every Snap you think is deleted, whether you opt-in or not.

And that’s not their fault, any more than it is not my fault that I don’t entirely understand the complexities of the American legal system the way lawyers do, or how the heart pumps blood to my brain, the way doctors do. It is the fault of the companies that have automatically opted them into it without thinking about the implications, without educating consumers, and most importantly, without asking and telling them what exactly they are collecting and where it’s being used.

So, when I’ve tried to convince friends and family to get off Facebook, to stop sharing kids’ pictures and tagging them for DeepFace, to turn off location services on their phones, to uninstall Instagram and the like, the ask mostly fell on deaf ears. Because, as someone who works inside the system, it’s very hard to explain in terms that make sense to a layperson why and how privacy is important.

But Netflix just explained the meaning of privacy by exposing someone’s very vulnerable viewing habits for millions of people. The outrage people feel means they still care about privacy. And, as much as I am worried about any kind of reprecussions for the Netflix employee if an individual person was responsible for the tweet, I hope it makes people scared and angry to understand even a sliver of what is possible, and I hope that people push back on Netflix. And, most importantly, I hope that this is the start of a sea change in American popular culture about what is ok and not with our data and a gradual move towards a balanced way of data collection and a retreat back to private, offline spaces, at least for a bit.