One of the best parts of having a four-year-old is that she’s finally old enough to request her own bedtime reading. Usually Mr. B does the bedtime routine and reading, but some nights it’s me, and we’ll turn on her soft, yellow chicken nightlight, and I’ll pull up a chair right next to her bed and read.

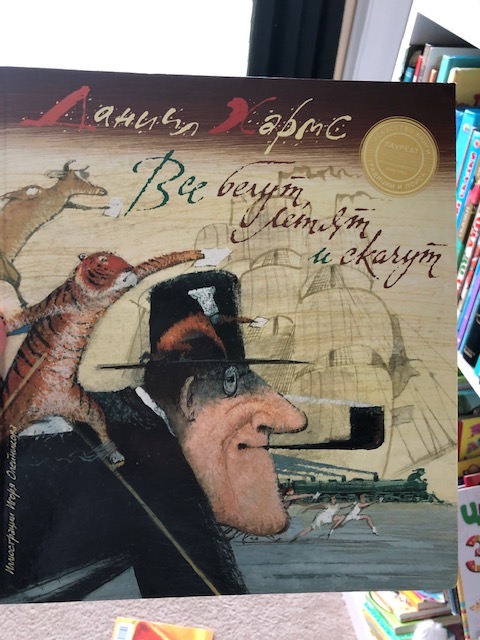

She has her own tastes and preferences, and lately, she’s been requesting Daniil Kharms’s “Everyone runs, flies, and hops”.

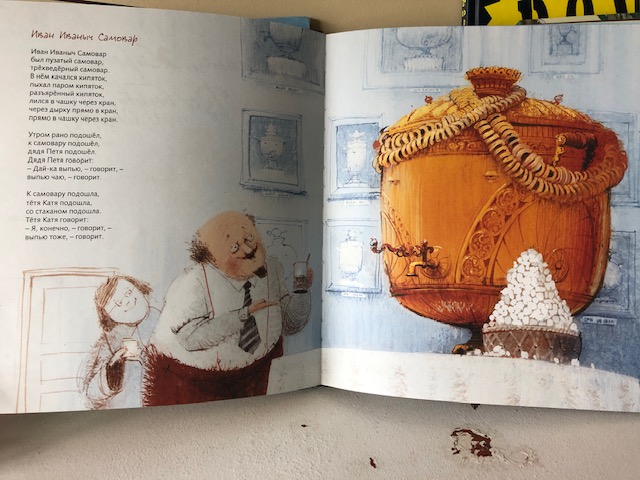

The book itself is one of my most prized posessions: brought over carefully from Russia by my aunt, it’s beautifully laid out and illustrated,and contains whimsical poems about samovars who don’t give tea to children who are late, cats who turn down invites to have lunch, and boys who turn into trains, planes, and automobiles when they’re playing.

As was the case with many Russian-language writers in the politically violent Soviet Union of the 1930s and 1940s, Kharms was an extremely talented individual who turned to children’s literature when he couldn’t get his real, avant-garde work published due to Soviet censorship.

Here’s an example of his work :

The first story I listened to was called The story of Sdigr Appr. Just the name of it alone should give you some idea of the contents.

The story starts by two men greeting each other and one stealing the other’s hand and carrying it for some distance. The men go together until the one demands to see a doctor who might also be a professor. The men go to the doctor and the thief gleefully proclaims he won’t give up the hand. The doctor says there’s not much he can do for the handless man, and in the meantime, the thief steals the professor’s ear. This goes on for quite some time until the professor’s wife tries to sew the ear back on, but the professor wants it on his cheek, so there it goes. The play/story finishes with everyone’s ears being stolen. The police are vaguely involved, but they also have their ears stolen.

Here is part of a poem the thief recites at the beginning:

Sdigr app ustr ustr

I am carrying another man’s hand.

Sdigr appr ustr ustr

where is the professor Tartarellin?

His real work is dark and nonsensical: characters suddenly dying or falling or killing other characters, or turning into animals.

He died extremely extremely early, during the godawful Siege of Leningrad, of malnutrition. As I wrote in my first blog post on Kharms,

His wife recalled an incident when she was trying to take him food during the Siege:

She made two long treks from her apartment to the hospital bringing packages, which were accepted, indicating he was there. The third time she went, two starving boys along the snowy path on the Neva’s ice begged her for help but she clutched to herself the tiny package of bread she was holding. When she reached the hospital the person at the window took the package and told her to wait. A few minutes later he returned, pushed the package back at her, and told her that Kharms had died. Walking home she wished she had given the package to the boys, though it would have been impossible to save them.

If you don’t know anything about Kharms, it’s easy to read his whimsical poetry at face value. Which is what my preschooler does, delightfully laughing at the poem about the man who turns into a snowman, the samovar that doesn’t give out hot water for tea to kids who don’t bathe,

For me, everything I read in Kharms’s work is an echo of his tragic life in a cruel society. There is a darkness under the layer of children’s literature that obscures the hideousness that formed it. This is true for all of Soviet children’s literature.

Samuil Marshak, one of the most beloved writers, was not allowed entry to university due to being Jewish. He picked up writing for children when his daughter died. Kornei Chukosvsky, probably the father of all fathers of Soviet children’s literature, was originally arrested in czarist Russia for some of his writing, and eventually criticized by Lenin’s wife, as well as fellow children’s author Agniya Barto. Agniya Barto herself managed to avoid criticism by writing anti-Nazi poems and sticking to light children’s poetry that had nothing to do with politics.

As a significant side note, all of these extremely Russian childrens’ authors were Jewish in a country with rampant anti-Semitism, which explains why some of them, like Kornei Chukovsky, changed their names to sound more Slavic (his original name was Nikolay Vasilyevich Korneychukov.) Agniya Barto was originally Gitel Leybovna Volova.

Russian history, and particularly the history of Jews in Russia, has not been a walk in the park and is characterized mostly by fear, suffering, discomfort, revolution, hunger, and silence. I want and need my daughter to understand this, and appreciate and respect her background and history, but not just yet.

Not just yet when she’s four years old and full of games, jokes, laughter, pigtails, and beautiful, beautiful sweet innocence that I wish I could bottle up and keep forever.

There is nothing as horrific to me as reading Kharms’s beautiful, fun poems to my daughter, and, simultaneously, thinking about him dying during the Siege of Leningrad. As I kiss her goodnight and she settles into a deep, comfortable sleep under her thick, warm comforter, surrounded by her five stuffed animals in the quiet American suburbs, I keep quiet, and she remains far away from the horrific ghosts of history.

Maybe that part - of keeping the world away - is really where the divide is between being a child and being an adult, and it doesn’t exist for just Russian children’s literature, but for anything that we hide away from our children, any layer that we abstract and strip the darkness away from, to keep them happy, young, and innocent and in pigtails, with popsicle stains on their cheeks, just a little longer. In that place where the scariest thing for them is that their chicken night light accidentally turned off.